Designer’s Notes: Mack Martin on Testing a Wargame Pt. 1

I’ll talk a little bit about my experience with Dust Warfare testing, but mostly this goes for any miniatures game (or any game as complex as a miniatures game). This was going to be a two part article, but now it’s 4! First I’m going to talk about the types of feedback you can get from testing. In the next articles, I’ll talk about what to look for during a play test, and some common balance decisions that many players might mistake for poor design, but which are actually quite healthy for a game. Don’t worry, I’ll also explain why!

There is also going to be a fair amount of jargon coming at you guys. I apologize in advance. So lets start off with some of the things that make testing really super hard.

Game Logistics

A computer game “pvp match” usually takes anywhere from ten to fifteen minutes. It involves 4 or more players, and the computer can track all kinds of information that real humans can’t watch in real time, like most common death positions. It’s also deceptively a more controlled environment than a miniatures war game, with set maps, ect.

By contrast, a miniatures game takes 2 players at least an hour to play. The board changes drastically (and randomly) and it is extremely difficult to monitor all the things going on in a game. How often did a roll come up more than one standard deviation above the norm? Is the unit too efficient at it’s point cost, or did the player just roll well? These are all questions that can only be answered with extensive notes… which increases a games play time to well over three hours.

So where a video game can test a bunch of games simultaneously over the internet, or even locally, a miniatures game takes three hours to test just one game. A game like Star Craft, or Halo, for instance, can push out a public beta, and have the computer run literally millions of games through a processor to find what happened the most. That can’t be done with a miniatures game… due mainly too…

Feedback Dataset Characteristics

Doesn’t that sound nice and sciencey? Basically there are four types of feedback that a designer can garner from playtests. They are each useful, very useful, but for different reasons.

Experiential: This one is pretty simple… is it fun! We are designing a game people want to play. The purpose is to have fun. If a player is excited about play testing again, and had a good time, that is extremely good information to have. If the players can pinpoint things that stopped them from having fun, that’s even better. It’s important, however, to note that this feedback usually only comes from new gamers. Experienced gamers tend to focus on the other types of feedback.

Mechanical: Also simple, the question here is about how clearly the rules are written. Wording can be made more clear from this feedback, or if it’s as clear as it needs to be FAQ questions can be compiled. Any game as complex as a miniatures game is going to need an FAQ. If the designer does this perfectly, there are still going to be questions that come up a lot, just because different people will read a sentence differently, or just misread something early on. An FAQ can help get everyone on the same page. The designer also needs to be on the look out for terms that might need explanation (like clockwise to younger players).

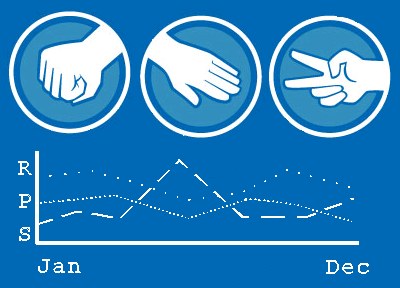

Balance: Now we are getting into tougher territory. This one is tied in closely with Metagame, but it has subtle differences. Balance just aims to make sure that one option isn’t head and shoulders more efficient than the rest. In a FPS (First Person Shooter) this might involve making sure every weapon has a maximum DPS (Damage Per Second) and that qualities like Splash damage are properly valued in the final DPS equation. In a miniatures game, it’s about making sure that one unit in an army list isn’t the best choice. Players will perceive best choices (based on the metagame, coming in a moment). Situation balance is critical to a miniatures game. Every player must feel like they have a tool to use to answer a variety of situations.

Metagame: This is the toughest one to test, but arguably the most important to a competitive miniatures game. It’s closely tied to balance, but it involves a pair of concepts I’m going to talk about later called Lead Position Disadvantage and Perfect Imbalance. This is possibly the hardest thing to test for in a miniatures game.

Coming up, I’ll talk a bit about how we go about getting each of these types of feedback during play testing, with the extreme time issues!

Have at it folks, and lets give it up for Mack! For more cool designer stuff, visit his site.