Designer’s Notes: Mack Martin on Testing a Wargame Pt. 4

Today lets continue our conversation on testing miniatures games. I wrote a little about testing here , here, and here and how it relates to miniatures games. Lets bring it all full circle.

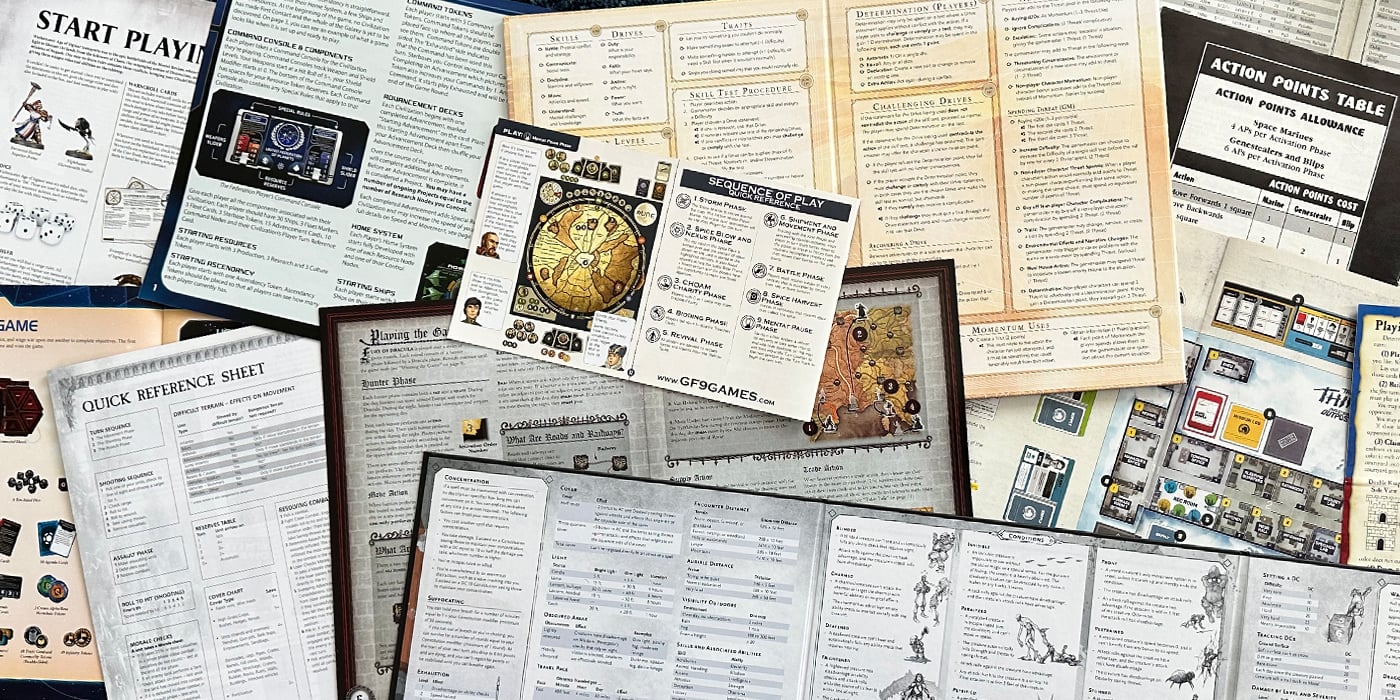

So by now I’ve hopefully shown you how challenging it can be to properly test a miniatures game. What’s more, the games are pretty complex, and we don’t have our own testing teams, not like the video game industry. The short answer to that… is money. A video game sells for $60, it might sell a million (or more) copies. That’s not even considered a big hit! That’s just a decent run. A big hit for a miniatures game would be a million copies. That’s a HUGE hit. And each copy sold isn’t nearly as much raw profit. Just mentally compare how much it would cost you to print a book, vs. how much it costs you to print a CD. I think you’ll see that books are much lower profit margin. That’s a considerably smaller amount of money that can go into development.

Players, on the other hand, expect fast updates. They want the books quickly. A company just can’t afford to build books at the rate the players want, for the price they expect. None of us want to be paying $200 for a game book. It would take budgets like that (or sales in the 10 million range) to make a miniatures game as finely tuned as a game like Starcraft. Even then, players will take issue with some of the decisions!

But what can a miniatures game designer do? Well he can watch games closely, and take notes. A miniatures game designer survives on passion, because there is no computer to compile the data for him. When I test games I do all the event recording by hand. Let me give you a list of things I need to know about every decision and dice roll a player makes.

- Is this action taking away from the fun of the game?

- Why did the player make this decision?

- Did he roll the correct number of dice, with the correct target values?

- How high above, or how far below, average did he roll?

- How common is it to roll this well or badly?

- How effective was the roll?

- How does this effect his current target priority?

- How efficient does this result make the units action?

- How will his opponent respond to the result?

I have stopped there, but there are actually 25 questions on my testing note sheet about each game turn. Thirteen are answered every time a player moves or attacks with a unit. These are the most telling, however,as the rest are just expounding on these when needed. A game (as noted in a previous article) takes about 3 hours to play in this fashion. I’m doing nothing but watching two players play, and writing these notes. It’s exhausting. If I miss something there is no going back.

So where does that leave playtesting? Well, most of it has to be done in house. Yes, we can do some external playtesting, but it isn’t as useful. This isn’t any fault of the play testers, they are a necessary part of the process and as designers we can’t thank them enough. But the simple truth, is that external playtests bring limited useful feedback. Lets talk about each of the types of feedback quickly, and how it pertains to playtesters.

Experiential: This is the easiest, and most players give this feedback without any prompting. “I liked it, few things I noticed…” that sort of thing. In early testing, I might ask them to rate it or I might also guide questions towards changes they think are more fun. I’ll also look for specific elements they felt stopped the fun for them, or created exciting moments.

Mechanical: This is also easy. I simply write down each question they had, and I make sure the next version of the text has an answer. I do NOT answer the question for them at the table. Instead, I ask them to interpret the rule, and I simply evaluate each case and determine how I can clean up the rules to make a complex concept more accessible.

Balance: Here is where things get sticky. Often, a player will feel a unit was over powered, when in actuality it just rolled well, or his opponent out played him. Some players learn new miniatures games faster than others, and this can be a bit of an ego thing. When a player feels a unit is over powered I ask him to look at his army options and attempt to thwart that unit in his next game. If, after 5 or 6 games, we indeed do have a unit that is above margin, I’ll bring in line. This testing, however, can’t be done externally. I need to observe the units in action. I need to know exactly what dice were rolled, and what the results were.

Metagame: This is where player impressions matter, but it is tied very closely to Balance. I can get a lot of opinions, but every player will have a different view, based on a variety of subjects. Some will want a game to function more realistically, some will want units to compare more favorably, and some will simply like a model and want that unit to be effective more often. Testing an evolving metagame is nearly impossible, before it gets out to the real world. You just can’t play enough games with the right level of feedback.

There is the trouble with external playtesting. The first two types of feedback can be given remotely. Did you have fun? Do you like the rules? Were any confusing? What questions did you have? That’s all well and good if the designer isn’t at the table with you. The next two, however, are things a competent designer might have a harder time gathering via email. It’s not impossible. With a large enough player pool, some tweaks can be made. If enough players feel that Shotguns are to strong, maybe they are. Dig deep, asking good questions of your testers, and it can happen.

Many playtesters can’t be expected to give this kind of feedback, however. They are volunteers after all! It would take a week of training just to teach them what to look for! Notes on every roll would just make testing a chore if I asked testers to do it. They test for fun, to help a game they love, and for the excitement of playing things early. So hopefully this series of articles helps to illuminate why external testing is so rare in the miniatures game world. External playtests are mostly a marketing tool these days. Yes the designers find them helpful, but not nearly as helpful as we would think. Even in video games, an external playtest might be less useful than a targetted test.

So this is the last article in the series. Let me sum up. External playtesting is helpful, but not nearly as helpful in the ways players want it to be. If you’re hoping that external playtesting will help tune the game balance an incredible amount… well that’s just not possible. We all wish it were, we designers are there with you! We wish that it was possible. Privateer Press came very close with their open beta. It was fantastic, and it definitely gives me hope for the future of miniatures games. I know I learned a lot from watching what they did. But at the end of the day, external playtesting is expensive, resource intensive, and the type of feedback received is only useful in a few areas.

Thank you for reading this incredibly long view of game testing. I hope it shed some light on the subject.

Have at it folks, and lets give it up for Mack! For more cool designer stuff, visit his site.