RPG Monster Spotlight: Owlbears

This week we talk owl about bears. No, that’s not it. We can hardly bear to talk about owls? Man, this week’s spotlight has really got me over a bearowl.

That’s right, this week we were wandering safely through the woods, minding our own business and not suspecting a thing when–oh look–owlbears came crashing into the spotlight.

Aww they’re so cute. And each cub can only kill about a third of a human in one swipe, so you’re probably safe petting them.

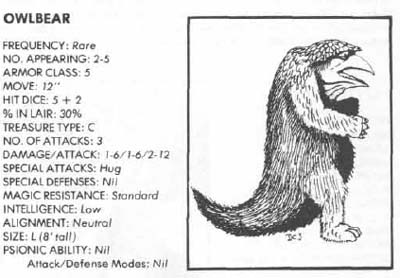

Owlbears are a mainstay of D&D, having been around since those heady 1975 pre-1st edition day, back when Dungeons and Dragons required Chainmail to play. Originally appearing in Dungeons and Dragons’ very first supplement, Greyhawk (because releasing supplements is another thing that’s been a staple of D&D since before they codified the rules into the AD&D books we all know and love), Owlbears were originally presented as being a bit like a werebear:

“OWL BEARS: Creatures of horrid visage and disposition. Owl Bears will attack whatever they see and fight to the death. They deliver a “hug” just as a Werebear, for example, as well as great damage from beak, tooth, and claw. A large male will stand 8′ tall, weigh 1,500 pounds, and have claws over 2″ long. Bodies are furry, tending towards feathers over the cranial region, and the skin is very thick.”

It had two claws which did 1d6 per claw (unless the owlbear hit with an 18+ in which case it dealt an extra 2d8 points of hugging damage), and a d12 bite. Very simple and straightforward–just a lumbering killing machine, and thus have they remained throughout the editions.

Whatever is going on in this book, that beholder is over it.

But there’s something to that simplicity that neatly captures how D&D feels. To be certain, they aren’t the only straightforward monsters out there, but something about their nature makes them perfect for the role of wandering monster. They don’t have to have a society or a kingdom, you don’t have to worry about a tribe of them banding to attack the town–they’re just a monster that exists in the world (and at the time for seemingly no reason). The literal definition of “random monster.”

Even their origins are random–they’re another “prehistoric monster” from the same set of toys that brought you the Bulette, Rust Monster, Umber Hulk, et al.

How many iconic monsters can you spot?

To this day, they remain one of the easiest monsters to throw at a party of adventurers. Is the game getting off tracK? Well, as one of my DMs used to say, “you chatty bitches are getting attacked by owlbears.” Then we’d roll initiative, tangle with the owlbears and be right back in the game. You don’t even really need an explanation as to why the owlbears are there–something about them just makes sense no matter what.

Pictured: Sense

You may not need an explanation for why there are owlbears, but 1st edition brought us a probable theory anyway:

The horrible owlbear is probably the result of genetic experimentation by some insane wizard. These creatures inhabit the tangled forest regions of every temperate clime, as well as subterranean labyrinths. They are ravenous eaters, aggressive hunters, and evil tempered at all times. They attack prey on sight and will fight to the death.

The first edition owlbear has gotten an upgrade from its Greyhawk predecessor. In addition to stylin’ new art that depicts the existential dread that every owlbear constantly experiences, it also had its bite upgraded from 1d12 to 2d6, making it twice as likely to kill your party’s wizard without even really trying. And, because this was 1st edition, canny adventurers were also told the price their eggs or young would fetch on the open market.

Still, I guess that plate armor won’t buy itself.

This one is being ridden by an Invisible Stalker.

In second edition, you can clearly tell that this is an owlbear (though the existential dread is still there in its eyes). Along with the new look, second edition also gave the owlbear a much more expanded ecology–one of the few good byproducts of the way monsters were originally released in second edition (for those of you who don’t know, 2nd edition originally released monsters in binders as part of a series of monstrous compendiums, so tracking down the monsters you wanted was particularly heinous depending on what your store carried). But the piecemeal nature of the release meant that they had time/room to expand the monsters a little more.

Which is why, for instance, second edition provides rules for fighting owlbear young (they do 1d4 per claw, and 2d8 per bite), as well as providing adventurers with some tips and tricks for dealing with an angry owlbear:

“Because owlbears are so bad-tempered, they stop at nothing to kill a target. It is not difficult to trick an owlbear into hurling itself off a cliff or into a trap, provided you can find one.

No word on what to do if there’s not a trap or cliff nearby. Get slowly digested, I guess.

Weirdly, in second edition the price of an owlbear depreciated, so adventurers with their capital tied up in owlbear futures saw heavy losses as they switched from gold to silver pieces. I guess this was an example of market saturation between editions, which makes sense, given that this is the edition which expands on the whole “a wizard did it,” angle, saying that wizards buy them to use as guardians or less subtle versions of keep out signs.

Second edition also saw the advent of the monster variants–and in Dragon #214 introduced arctic and flying owlbears (the former was particularly good at hiding in the ice and snow and could launch a deadly surprise attack, the latter was an owlbear, but it could also catch flying prey), ensuring that nowhere was safe.

Third edition owlbears got a little more deadly, even if they looked more like an owl had been bitten by a werewolf and now had some freakish lycanthropic hybrid form. But I digress–third edition made owlbears a lot more deadly, not because of their bite (which saw a downgrade to merely a single d8), but because of their “hug.”

This was the edition that formalized the grappling rules to be more then just “make a bend bars/lift gates roll,” which meant that owlbears were a little more fearsome, both because they had improved grab (which let them add a grapple attempt to any claw attack they made for free), but 3rd also made being large much more of a big deal. With the bonus to strength and grapple checks, any adventurer would be hard pressed to escape an owlbear’s clutches.

It also provided rules for taming the owlbear (and for those of you following the owlbear market at home, prices went back up, rising from 5,000 silver to 3,000 gold). No word on egg prices, so perhaps they became more mammalian in third edition? You decide!

Fourth edition owlbears were a lot more ferocious. They gained “elite” status, meaning that a pair of them was meant to be enough to challenge a party. They had increased armor class and hit points to reflect that. It’s claws and bite did double the usual damage (2d6 and 4d8) even though the owlbear could only bite grabbed targets. It also gained the ability to issue a stunning screech when dealt enough damage.

Keeping the traditions of second edition alive, fourth edition also included a winterclaw owlbear as a variant (I am legitimately surprised that there aren’t more of these, I could see a winged owlbear, or maybe an owlbear knifebeak that was some kind of assassin hybrid thing). This is the only edition to drop the “wizard did it” explanation. A mistake they soon rectified.

Fifth edition sees the triumphant return of the owlbear’s origins as a twisted experiment done by a demented wizard. They also allowed that some owlbears might have been around in the Feywild, but, we all know the truth.

So does the monster manual, as it includes the following note:

“The only good thing about owlbears is that the wizard who created them is probably dead.” – Xarshel Ravenshadow, Gnome Professor of Transmutative Science at Morgrave University.

Fifth edition also introduces a number of subtle improvements to the owlbear, playing up the owl aspect a little, giving it advantage on any checks involving sight or scent, as well as increasing the damage dealt by its claws–they grew to 1d10, which you can understand, given those beefy arms up there.

And fifth edition also introduces my favorite thing about the owlbear–in their effort to add more narrative elements to their entries (without overpowering the rules), they detail “owlbear races,” which are technically supposed to be all about seeing which owlbear wins the race, but which often as not is all about which owlbear attacks their trainer first.

The owlbear has been largely unchanged throughout the edition. They represent the simplicity of the rules at their finest. You don’t really need to complicate things to have a creature that acts as a threat–even if they’re never the climactic encounter to an adventure, owlbears liven up any encounter they participate in.

So whether you need wandering monsters, or some delightful flavor to add to the nearest frontier settlement, you can’t go wrong with the Owlbear.

What other owlbear variants can we come up with? Got an owlbear story? Let us know in the comments below!