RPG: Blades in the Dark Review

Blades in the Dark is a game of skulking thieves trying to make a big score–and so much more…

Blades in the Dark is a new RPG out from John Harper and the fine folks at Evil Hat Productions. In it, you and your friends become daring scoundrels trying to carve out a niche for themselves in a haunted, industrial/fantasy city where ghosts and worse stalk the streets. Where a rival gang might spell the end as easily as one of the Bluecoats who are there to keep the city “safe.” It is a game of fortune and fools. A game of Blades in the Dark.

Blades of the Dark is, without a doubt, one of the better games I’ve come across in a good long while. From the top down everything fits together like a well-geared machine. It’s not without its stumbling blocks, for me, but this game has so much to offer once you start digging in. So, with that out of the way, let’s start digging in and see what makes this game tick.

Style with Substance

For starters, this game feels slick. They set out to accomplish a very specific goal–playing a gang of scoundrels, and they achieve it on every level. To give you an idea of what they’re going for, I’ll borrow their particular cultural touchstones–if you’ve watched Peaky Blinders, played Dishonored or Thief, or read the Lies of Locke Lamora or Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, you know the aesthetic they’re going for here.

This style is present at every layer in the game. It’s in the way the game plays: this is one of the best methods for handling heists/robberies/crimes/missions I’ve come across. There are rules to help make carrying out a heist a fun and engaging activity, rather than an hours-long slog of hacking through every little detail. It’s all in the way they frame it. Players don’t sit down and plan the nitty-gritty details of the heist (or whatever), they figure out a plan their characters have already come up with and adjust it on the fly.

There are a few basic types, which describe in very broad terms the sort of action your characters are undertaking:

- Assault – Do violence to a target

- Deception – Lure, trick, or manipulate

- Stealth – Trespass unseen

- Occult – Engage a supernatural power

- Social – Negotiate, bargain, or persuade

- Transport – Carry cargo or people through danegr

And then depending on what you’ve chosen, it’s up to you as characters to provide some of the missing details–like the point of attack on an assault mission, or the way you’re going to deceive someone for a deception mission. After that it’s all a matter of making engagement rolls which are how you help set up the scene–this can include calling on allies, or finding out that there’s some unforseen consequence like an extra guard detail in due to a visiting dignitary. There are even rules for handling the classic “flashback reveal” moments that are a staple of the best heist movies. In Blades in the Dark, it’s just as easy and appropriate to respond to the sudden appearance of a guard by saying, “of course, this is one of the guards we’ve bribed previously to let us past,” and then, depending on how your luck holds out–that may well be what happens.

Of course, it’s also possible that the guard could just double-cross you, or demand extra favors.

It all comes down to how the system handles conflict. It’s a rather elegant system. I’d say it’s one of the most simulation-y narrative systems I’ve ever seen. What the heck does that mean, you might be wondering, spitting out your expensive coffee in disgust, both because of that comparison and because the Barista definitely used soy when you explicitly requested almond milk. Well calm down and wipe your screen off. All I mean by that is that the game does a very good job of representing certain concepts that need to be present in order for the game to work narratively, even if the specifics are a little abstract.

It reminds me of the narrative approach of something like an Apocalypse World, for instance. Only instead of giving you a very broad set of rolls that can mean a great deal depending on the situation, you’re given a suite of abstract things that simulate the various pieces of the kind of narrative this game sets out to represent.

Let’s take a look at a classic concept: combat. Combat in Blades in the Dark is very different from something like Dungeons and Dragons. In D&D you have both a player and a monster represented as distinct entities with their own pools of health and discrete actions. Fights are broken into encounters which themselves might be built out of individual monsters who all work together to make a fight that happens turn by turn.

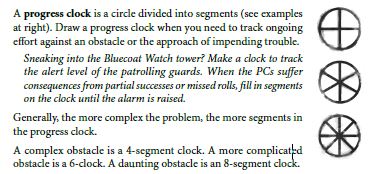

In Blades in the Dark, however, combats are a little more abstract. They’re there to represent the narrative beat of having a group of characters get involved in a rooftop swordfight with a gang of assassins, say. But whereas in D&D this might be represented with a number of individual assassins, in Blades in the Dark the entire gang would be considered as a single entity–one obstacle that the players are there to overcome. There’s a rules mechanic called the Progress Clock, where the GM sets up a “clock” for a given obstacle, and as the players make their actions either ticks or unticks segments of it to represent the overall flow of the obstacle, in this case a gang of assassins.

So in our assassin example, we might determine that the assassins are skilled, but by no means elite, and assign them a 6-segment progress clock, which the characters can fill by making successful attack rolls.

That’s sort of the core concept. It’s a rule that gets used to represent any sort of difficulty though. I will say that’s one of the few critiques I have for the game–and one I have for many of the narrative heavy games in general. It’s possible to get too abstract at times–escaping a burning building is mechanically similar to fighting a gang of assassins. But where Blades in the Dark stands out is that, even though the core mechanic is the same, it provides for enough narrative style to make the two activities feel different.

It definitely needs a GM that is attentive to the overall state of affairs. But, once you get past that initial abstraction hurdle a whole world opens up. You can link progress clocks together to represent particularly complex affairs–you might have one for “the hideout of the Midnight Ravens,” but its progress relies on the PCs filling in another clock for “Midnight Raven patrols” and “Perimeter Security.”

You can have racing clocks–one might represent the PC’s escape attempt, while another called “cornered” represents the guards’ pursuit. And depending on which ends up filling up first the PCs escape or are forced to fight–and so on. Like I said, it’s a little abstract, but once you get the hang of it, you can use it to represent just about anything you’d need.

The Characters

Then there’s the characters themselves. As mentioned, this game is all about style and these characters feel cool. You’re all assumed to be scoundrels, but the specific kind of scoundrel is up for grabs. You might be a Cutter, adept at fighting and intimidating, a Hound–a deadly sharpshooter and tracker, a Leech, who handles all the sabotage and other thieves’ tool sort of activities, the Lurk, skulking around in shadows unseen, the Slide who is a manipulator, spy, and liar extraordinaire, a Spider, spinning webs of schemes and plans that the party is invariably entangled in, or a Whisper, who commands the supernatural forces that inhabit the city of Doskvol.

These “classes” each come with their own abilities that help distinguish them. As you earn XP you advance your character by selecting from a list of abilities unique to your archetype–and just a quick word on XP–it’s not up to the GM to award it. It’s the players who determine whether or not they’ve met the conditions necessary for their advance. That’s something I really like about this game in particular. They come out and are very explicit with a certain set of assumptions. You’re here to tell a story and it’s about a conversation between the Players and the GM. They even go so far as to outline a system of “best practices” for player and GM that is hands-down one of the best “how and why to play a roleplaying game” chapters I’ve read. Blades in the Dark understands exactly how to get what it wants out of player and GM alike.

The way this game encourages and expects teamwork is the best way to illustrate this. So these kinds of stories are all about a crew of thieves. Blades in the Dark wants to capture the feeling of carrying out daring heists and deadly ambushes in a city where you have to work as a team to survive. The game takes every opportunity it can to reinforce this idea. You get a benefit (and even XP) for helping your team. You can lead group activities. And of course, your collective Crew has its own character. As your Crew levels up and you acquire more turf for your gang, you advance your empire–effectively having a collaborative character. One that provides actual mechanical benefits though.

All the rest.

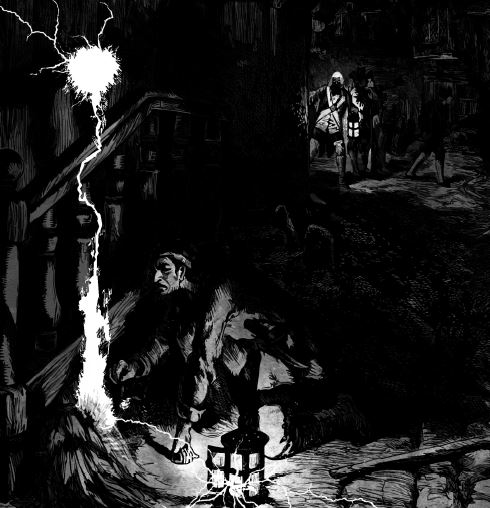

We’ve only barely scratched the surface here. We could talk about the setting–a mix of criminal underworlds and creepy industrial gothic fantasy. In the city of Doskvol, when a body dies, a bell rings in the great crematoriums of the city, and spirit crows set out and circle closer and closer to the body until they mark where it is–then a team of body retrieval specialists goes and collects it, so that they can burn it and prevent an angry ghost from forming.

You can have characters that carry out occult rituals, or that bind spirits to industrial objects–called sparkcraft. Basically you can take this game into some dark, eldritch places if you so desire. Or if you have had enough of the setting, you could look at how deftly it handles confrontations, leaving it up to Players and GM alike to figure out outcomes–especially with mechanics like the Devil’s bargain (where you take a negative consequence in exchange for bonuses on an important roll), it all comes together so well, and I highly encourage you to check it out for yourself.

I seriously cannot say enough good things about this game. It’s very particular in what it’s there to accomplish,* you won’t get the same satisfaction if you want very crunchy combat filled with exchanges of HP and where the game basically helps you simulate the world. You have to take an active interest in the game as it unfolds, so players who like to sit back might have a little bit of trouble.

But, it gives you such a great toolset that is flexible and fun. I think it’s definitely worth checking out, and I am looking forward to running many campaigns using this system.

Check out Blades in the Dark $30-$50

~In the meantime…stay sharp out there. Keep your blades close and ready.

*Leaving aside for now the whole chapter dedicated to hacking the game and using it to possibly represent other genres, or the sizeable Google+ community out there where you can find things like a Firefly-inspired take on these rules, of course.