40k: A Teacher’s Perspective on Welcoming New Players

With this article I’m hoping to add something different, instead of talking about tournaments I’m going to talk about playing with new players.

Guest submission by Fredrik Lindqvist, lightly edited for clarity

I’d like to approach this from a teacher’s perspective (I live in Sweden and teach Swedish to migrants), so I’ll teach you something about pedagogy.

My first encounter with a gaming group’s “old guard” severely impacted my gaming habits. In fact, my friends and I went there because we wanted to start playing Warhammer Fantasy. Our initial treatment was so bad that we decided to form our own group and start playing 40k instead. My experience learning Infinity was worse. I don’t play that anymore.

Two years ago, my brother picked up 40k and I’ve been trying to teach him to play. So far, he’s still only played me. My brother is a very intelligent man, a win at all cost player that studies every rule, keeps track of the meta and heck, his very first list was a net-4-flying-daemon-prince-shenanigans-list. There’ll be some references to him and my students throughout this. Let’s begin with talking about how we learn.

Knowing Your Student

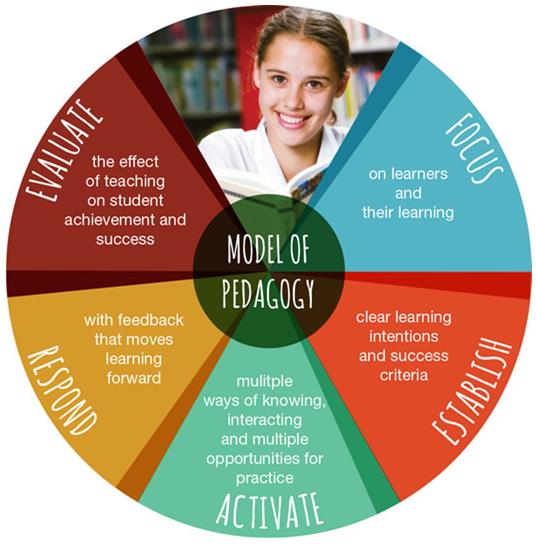

Before you start to teach a student, you need to assess where he is unless you know he is starting from scratch. There are two forms of assessment. Summative and formative. Most assessment in school comes in the form of written exams or essays.

- A summative assessment looks like this: “You get an A.”

- A formative assessment looks like this: “I see you aren’t using capital letters at the beginning of your sentences, review page 4 about the rules regarding capital letters and correct your mistakes.”

Assessment is key in order to know where your students/players are. Otherwise, you end up with students that are in too deep water and give up or players that are still learning the phases facing off against professionals. Research says that formative assessment is more conducive to learning. Try to stick to formative assessment. The important part is to keep it short, to the point, and only about the subject. I’d stay away from summative assessment because it can be degrading if it’s not from an official source.

Real life examples: Every time we get a new student he must take a placement test to see how proficient he is in the language. If we didn’t do that he might end up in a class where he’ll just fall further behind because it’s too hard or he’d be bored out of his mind in class that’s too easy.

When I was teaching my brother how to play, I always tried to give formative assessment after each match to make him see where he could improve.

Adjusting the Level of Difficulty

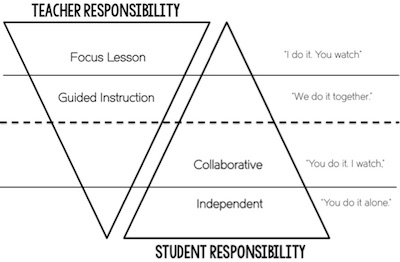

The Zone of Proximal Development (ZoPD) is where learning takes place. If you imagine an area and all you know about the subject is put into that area. The zone just outside of that area is the ZoPD. That is what you can learn by yourself or with minimal help. Let’s call that zone +1. Each zone outside of that will require more and more help. You could still achieve a learning goal in, for example, zone +4 assuming you get enough help to understand the subject matter. This help is generally called scaffolding. You provide the needed structure for them to construct their own knowledge.

Real life examples: When learning a new text type. I provide my students with a prewritten structure and instructions of what they should write in each area.

My brother had no problems with the general rules but the more competitive and experienced based concepts such as not chasing a squad of scouts across the map with 800 points of Daemon Princes was not there in the beginning. In order to have a fair match, I told him each turn what I would do, what I attempted to achieve and what I was afraid that he would do and why. Even today two years later, I still fall back into that if I feel that the match is going too much in my favour. Although that’s rare. From what I’ve understood, this is what he appreciated the most out of all my attempts to teach him. I did it for a long time to a diminishing degree until he started mopping the floor with me without it.

The Need for a Safe Learning Environment

The affective filter is a term used in pedagogy. Even if you’ve never heard of it I promise that you’ve experienced it. A learner can have a raised or lowered affective filter depending on how the student is feeling. Things such as comfort levels, stress or emotional state can affect it. It’s generally believed that a lowered affective filter leads to better learning. Think of it as a shield protecting your brain and pride from too much information or a task that is too hard. You know how when you are about to start learning something new and your brain goes: “NO! TOO HARD, UNFAIR, I DON’T NEED THIS.”

The absolute worst thing you can do is to attack their pride by for example standing with your arms crossed and say “go look that up in the rules, I’ll wait.” They just aren’t receptive right then. Instead, you might need to refocus their attention, maybe on just making them happy, or maybe by making them focus on a single aspect that is within their ZoPD. In a raised state, a student’s perspective of events can be severely skewed, making it even harder for them to take things in.

Real life examples: When I correct my students they often fight back. This is obviously not because they believe they know Swedish better than me. It’s because they are experiencing the situation as threatening to their pride.

When my brother was being particularly defensive against my Primaris list, he sent me a copy of what he thought I fielded. There was an extra 1000p and almost twice the number of squads. His hate against my Inceptor squads obliterating his brand new Great Unclean One completely skewed how he experienced the rest of the game despite him winning it. It wasn’t until much later he was able to turn it into a learning experience.

Unintentional Communication

A lot of things can be offensive to a person’s sensibilities, such as body language or choice of words. If the learner is feeling demeaned, even by accident, they might respond aggressively. Due to my students’ current level, these days I consider charades to be my second language. All non-verbal communication has made me reevaluate a lot about my behaviour when I realised that my previous military career has left me somewhat… stern.

The next time you play. Think about how you stand. I don’t know about Pimpcron but I usually have my arms crossed, a quite intense look as I’m scanning the battlefield, and I’m generally quiet as I’m trying to take things in. Not exactly friendly to a new player. If things go badly, I’ve more than occasionally slipped up and said negative things like “insane luck” or “that’s OP” or gone into a “friendly discussion about why that unit is unfair”.

Summing It All Up

We see this happen in gaming groups – without assessing a Noob’s skill, a member of the “old guard” asks a new player to play a game with him. The veteran player places the Noob on display as his friends look upon this match from across the room. He then proceeds to whip out a somewhat demeaning list and start playing. During the game he constantly corrects the Noob, forcing the Noob way out of his ZoPD while probably providing a healthy dose of arrogance or haughty demeanour and insufficient scaffolding. The Pro is then surprised by the sudden offensive nature of the Noob’s raised affective filter. Everyone gets angry, the game goes poorly.

This scenario can be totally avoided if you take a little time to talk to your opponent, and be more understanding of new players’ lack of experience. Hopefully this will help you the next time you see a new player.

If you like this article I would gladly write another about how you SHOULD approach new players to make finding new memebers for yout gaming group easier, and make the learning experience more fun for everyone involved.