D&D: Waterdeep Dragon Heist – The BoLS Review

Waterdeep: Dragon Heist sets adventurers on the trail of half a million gold pieces, racing against one of four different villains, all the while getting wrapped up in the midst of Waterdeep, the City of Splendors. How does it stack up as an adventure though? Read on to find out.

Urban adventures are a strange brew. Compared to the earliest D&D modules, they turn the idea of Dungeons and Dragons on its head. Where the first modules used a city as a hub for adventurers to restock in before heading out for the nearby Dungeon, maybe triggering a random encounter or two along the way, urban adventures, as the name implies, set the action in and around a city. Or town, or thorp, or hamlet, or Hommlet. The alleyways and hidden warehouses become places where heroes clash with thieves’ guilds and cultists. Guards stick their noses into places you wish they wouldn’t. And through it all there’s constant opportunity to roleplay, even if it is just buying another round of healing potions from the magic item shop.

Waterdeep: Dragon Heist is one of the best examples of an Urban Adventure that you can find. Full of a plot that, from a distance, seems a little railroad-y, as you get close you’ll find that this adventure breaks from the norm, giving players and DMs alike a little more freedom. Instead of laying out a plot that strictly leads from A to B to C, the book sets up a number of moving pieces, and whenever event A happens, you could potentially trigger B or C or find something else. It’s very sandbox-y, but it’s structured play within the sandbox. And the reason for this, is that Waterdeep: Dragon Heist tries to experiment with the way we think of low-level parties, low-level adventures, and low-level D&D in general.

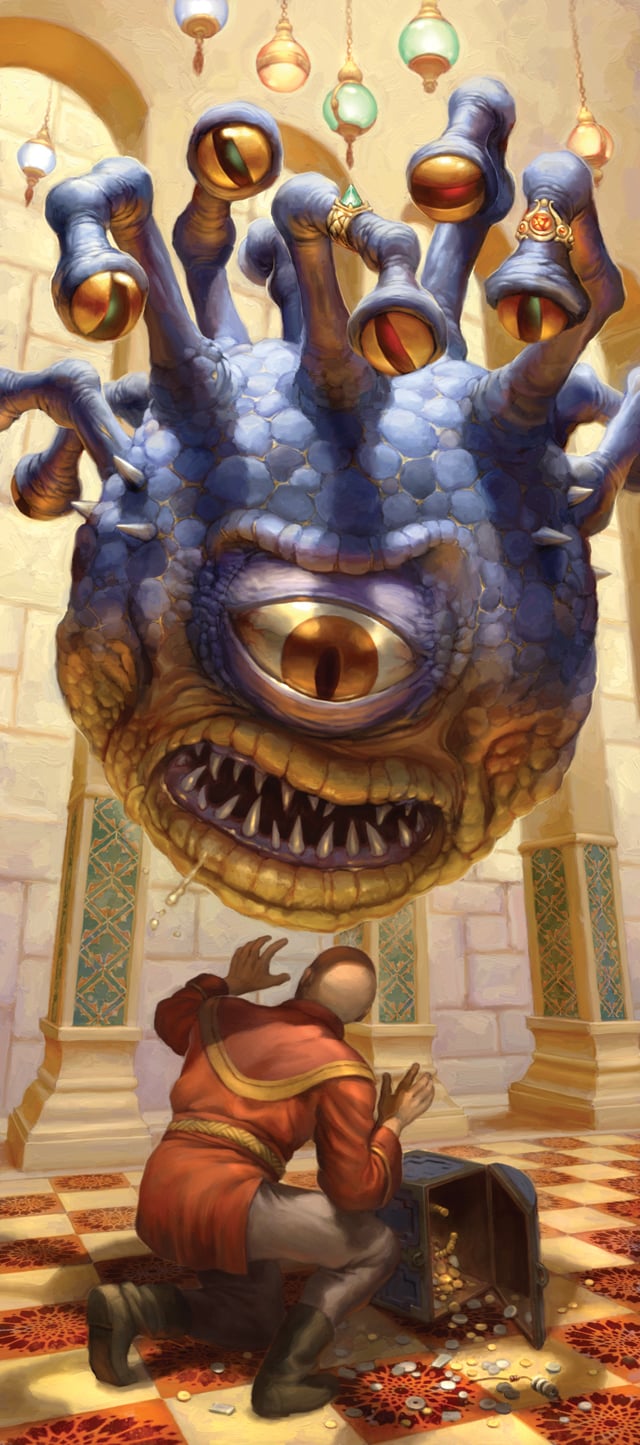

For most of us, the low-levels of Dungeons and Dragons are a fact of life. Nearly every campaign starts off in that level 1-3 zone, where players still go out and sort of scavenge for every scrap of gold they can while barely managing to stay ahead of the hobgoblins and gnolls that they have to contend with. Not so, says Waterdeep: Dragon Heist. Just because your characters are 1st level, doesn’t mean they can’t enjoy themselves. Doesn’t mean they can’t be pitted up against the movers and shakers of the world. Quite the contrary, Waterdeep: Dragon Heist wants you to get in over your head. It wants you to come face to face with the Xanathar and try and scrabble out of it by the skin of your teeth.

And by and large, Waterdeep: Dragon Heist lets you pull that off. Or at least, it gives you the tools to do it and says, “good luck.” And I love that about this game. You can see this ethos present in the way the book is structured. Chapter 1 is an adventure in the city. Chapter 2 is mostly an opportunity to roleplay within Waterdeep, with very little happening that moves the plot forward–but it’s probably one of the most charming chapters out there. Chapter 2 is an introduction to the neighborhood of Trollskull Alley. You could possibly play through this entire chapter in a single session, or you could stretch it out over weeks, depending on how you like it.

As I said, nothing happens to more the plot forward–but it’s because of this freedom that the chapter really shines. There’s so much personality and character to it. Trollskull Alley feels alive, and it’s the perfect way to get characters invested in the different factions of Waterdeep (perhaps they’ll take on some sidequests), as well as giving characters a base of operations which feels like an important development for the way wealth in D&D is perceived, and is perhaps one of the most underrated things in the book.

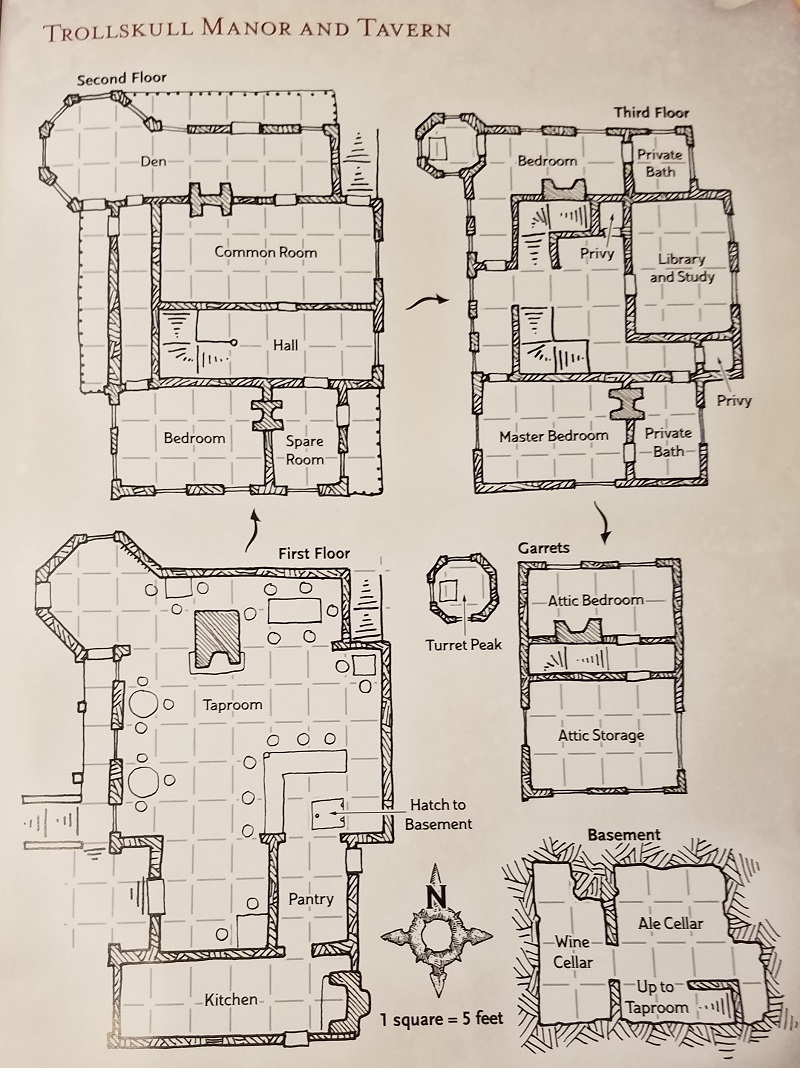

You see, the adventure gives the characters property. By the end of Chapter 1, if they successfully complete their quest, none other than Volothamp Geddarm hands them the deed to Trollskull Manor, a rundown, poltergeist-haunted inn in Waterdeep. This is amazing. It gives players a stake in the world around them. And right at 2nd level at that. So before you even have time to make a subclass choice for most of the classes, you’ve got the deed to a rundown inn. It even has a map to go with it. It’s this real, concrete thing in the world, and it’s yours. You can take a look at the map, decide to find some nice chairs to put in the taproom, and then draw them in. And then boom, you’ve done it. You’ve made it happen. You’ve changed the world around you. And that attitude–the idea that you can change the world and make something your own–is going to give so much vibrancy to games.

At 2nd level, when players are trying to figure out what their fighting styles will be like, Dragon Heist is asking players what they want to be invested in. It’s showing them their actions have consequences, and giving them something to look forward to. And more importantly, something to spend money on. Not to get too sidetracked from the other chapters, but Waterdeep: Dragon Heist has one of the best attitudes towards treasure in any D&D adventure. Simply put, treasure isn’t meant to be carefully hoarded. It’s best when it’s used to get players immersed in their world. Which is a breath of fresh air compared to the usual way treasure is treated in a D&D adventure. Players might even find themselves owners of the half-a-million gold coins at the end of the adventure–and the adventure is fine with it. Better than fine, it says, “Okay so you have 500,000 gold pieces…now the real adventure begins,” and it gives you guidelines for what to do now that your players are rich beyond their wildest imaginings.

Chapter 3 gets the plot moving again, taking players through an inciting incident that acts as a weathervane for how your party will handle things like urban investigations, tracking targets, and how they interact with the city. At each step of the way, they’ll have a chance to bring the guards or the agents of the Lords of Waterdeep (or their enemies, depending) in on the search for the treasure. Which is good, because if you’re going to survive an encounter with one of the main villains, you’ll need the protection (or at least the promise thereof) of someone just as powerful in order to help you keep your skin. There’s a lot that smacks of good intrigue in this book, so if you’re looking for a guide on how to put together courtly intrigues, this book actually isn’t a bad start, which is surprising to me.

Chapter 4 is the climax of the adventure. Here’s where we see players actually pursuing the object of the adventure, and going through a series of encounters that can kind of shift depending on what villain you choose. Which, in case you didn’t already know, one of the other experimental things about the book is that you can pick your villain from one of four. And each of them come with their own goals, their own motivations, their own minions and special events. In Chapters 5-8, you’ll find every villain written up with their own set of special encounters that can potentially happen–including ones that change the ‘official’ story of what happens down in Waterdeep.

And that’s it—8 Chapters of Adventure plus 25 page Enchiridion that takes Waterdeep and makes it feel alive. I can’t say enough good things about this book–it’s a much different flavor than WotC’s usual fare, but I love it. Whether it’s the motivations of the villains (you can really feel for some of them), or the way it sets up DMs to try and make this adventure theirs, this book does some important work. And, like any good RPG tome, it makes me want to sit down and play some D&D. Be sure and tune in later this week as we delve through more to see what else Waterdeep: Dragon Heist has to teach us, including a look at design philosophy and social encounter construction.

Until then, this book is highly recommended, and Happy Adventuring!