D&D World Building Workshop: The Rule of Defaults

Let’s talk about some rules you need to keep in mind when building your world – and how assumptions can be potent tools.

There comes a time in almost every DM’s life when they want to move beyond the existing settings and create one of their own. Maybe you have an amazing story to tell, and it needs its own world to be told in. Perhaps you have a super awesome idea for a world and want to run adventures in it. Maybe you just like making up settings. Whatever the impetus, creating your own setting can be fun and rewarding both to you and your playgroup. In this new ongoing series, we will look at the steps you can take to create your own setting (a process known as world-building), and we’ll look at some tips and tricks of excellent world-building and some common mistakes people make. Along the way, we will build our own setting and world.

Welcome to World Building Workshop, let’s get started.

Warning: This Post Contains Spoilers For Captain Marvel (2019)

The Groundwork

Last time on World Building Workshop, we talked about how you can tell your players about the world. We discussed ways to get information to your players and however, you can build it into all aspects of your world building. Now I know last time I promised we’d talk about maps next, but I realized I was getting ahead of myself. We’ve still got a few rules we need to go over before we get to maps. Let’s go over the first of these, which I think of as the Rule of Defaults.

What Is This Rule?

The way this rule works is that unless you specifically tell your players that something works or is different from what they know, they will default to assuming it works the way they are familiar with. For example, in the real world, rivers run from high ground to low ground, the sky is blue, and the world is round and orbits the sun. Now, when you build a world or setting, none of these things have to be true. In your setting the rivers could flow from the sea up to mountain lakes, the sky could be green, and the world could be a flat plan stacked on many others and lit by a god riding a chariot. These are all possible in your made up world. However, if you do not explicitly tell your players these things, they will assume that the default, the real world conditions, are true and will act accordingly.

This is true of fantasy elements as well, especially if you are using an established setting like D&D. In your world again, Goblins could be noble, well-educated scholars and elves could be cowardly folk who are scared of the sun. However, unless you tell players this, they won’t act like its true. Instead, they will treat the races as they are portrayed in other works of fiction, and in particular in D&D products like the Players Handbook. These products describe many of the fantastical elements of the world in a specific way. Players will naturally default to assuming they are true in your world unless you tell them otherwise.

How Default Expectations Can Cause You Trouble

At the start of your game players assuming the default is true can be cause for confusion. One player might want to play an Elf Wizard, a classic choice. In your setting however Elves are a non-magical race, their connection was severed eons ago and is a significant plot point. Since you never told your player that she wouldn’t know she can’t play an Elf Wizard. This is quickly fixed by a discussion in the planning phase of your campaign and shouldn’t cause real problems.

When the issue comes up later in the campaign; however, it can cause real problems. Let’s say for instance you players come upon a group of Goblins. It would not be out of character in a default setting for the players to attack the evil goblins, ridding the world of their danger. You let this happen, you appreciate player choice after all. Later the players are shocked to find they killed a bunch of peaceful scholars. If the characters should know that the Goblins were peaceful, but it wasn’t properly communicated to the players, they will most likely be upset, feeling upset and confused. Likewise reveling surprising facts about the world late into a game can hurt the immersion and consistency of the setting – worse if this unknown fact causes the players to fail at something it can feel like you are making things up to cause them to fail. This is not good for anyone. Bottom line: if the characters should know something, make sure you tell them.

How Default Expectations Can Help You

The bright side is the rule of defaults can be a big help to you in your world building. The default expectations of your players are cheats and a shortcut to world building. Assuming things in your world work, the way the players are similar with; you don’t have to take the time to spell it out for the players. You don’t have to take time to go over how rivers work, or the rain cycle, players will already know this. If Wood Elves in your setting are tall, thin, graceful beings with long lives, that live in trees, use bows and are slightly arrogant at times, you can get away with just saying, these are Wood Elves, and your players will know what you mean. Likewise, if you chose to use the standard D&D pantheon of gods, just say that, and the players will know what to expect. This can speed up things at every level of the game.

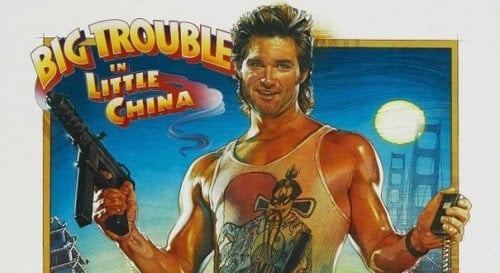

We’ve been conditioned to assume which of these is the good guy and which the bad guy, but are we right?

You can also use the rule of defaults in your storytelling. Let’s take the above example of the players attacking a group of Goblins. Let’s say again in your world that Goblins are good peaceful folk with love for learning. However, in your setting, the “civilized” races still treat them like a standard D&D setting and think they are evil beings to be exterminated. The player’s characters would naturally share these prejudices. Thus you could make them attacking the Goblins not about you failing to tell your players something since its knowledge their characters wouldn’t know, but make it into a lesson about the in-world prejudices. (You can see a similar thing in the recent Captain Marvel movie. The audience assumes the Skrulls are bad guys based on their names and their goblin-like looks, and for comic fans on the fact that Skrulls are villains in the comics. In fact, the Skrulls are the good guys in the movie.) In essence by knowing and understanding your players’ expectations you can subvert them. Just make sure you are doing it for the sake of the story, and not for shock value alone.

Have you ever gotten into trouble due to this rule? Let us know down in the comments!