RPG Monsters: It’s A Mimic’s Life For Me

When the monster can be anything the fun never stops. It’s time to take a closer look at the Mimic!

The monster was…right here a second ago…hang on, maybe it’s hiding in that chest… Huh, nope, it’s not there. Well where could it be? Maybe it’s the desk? Oh geez guys, this is embarrassing. After all this trouble we went through–the trip to the underdark, the three lost hirelings who helped us “identify” the monster, and the long haul back (including the unfortunate incident with the shipping container) we’ve gone and lost the monster we were hoping to drag into the spotlight. So, I guess, be careful–it could be anywhere. It could be anything.

Each of those mimic minis is itself an actual mimic. Mimiception.

The Mimic is a quintessential part of D&D history. It has its roots in Gygaxian dungeon philosophy, where just about anything in the dungeon can and should be a dangerous threat to the party. Players should never be allowed to rest on their laurels. Mimics are one way of ensuring they never get too comfortable. Even discovering a reward can be a threat.

The lesson here is never trust anything. Especially when you think the GM is handing out treasure–the mimic is a perfect example of how to prey on the minds of the players (not just the characters). This was something Gygax loved to do, he’d come up with traps and puzzles that were meant to mess with the people sitting across the table with him, that’s why things like the Tomb of Horrors are so legendary.

Mimics are just a natural evolution of that drive. And I think there’s something that’s approaching the platonic idea of a D&D monster in these creatures. They’re monsters that don’t necessarily have a rhyme or reason–though later they’d be monsters of the underdark–but they could sometimes be friendly, sometimes deadly. Whatever the case, things always get interesting when you have a monstrous talking treasure chest nearby that’s hungry for adventure(rs).

The 1st Edition Mimic is where it all began. Back in 1977 in the 1st Edition Monster Manual, we got out first glimpse of these subtertranean creatures that were described as being unable to stand the light of the sun. Capable of perfectly imitating stone or wood, these mimics came in two varieties, the smaller 7-8 hit die mimics, which could sometimes be friendly (and were more intelligent than their larger compatriots) if they were given food. These (sometimes) friendly mimics could sometimes aid an adventurer, offering advice about what they’d seen recently.

The larger, 9-10 hit dice ones attack everything indiscriminately, as you might expect.

Though the one pictured is a chest, Mimics could also pose as stonework, doors, chairs–any kind of object that is composed of the substance they can imitate. Then they lay in wait for a creature to touch them, at which point it lashes out with its pseudopods and adhesive glue, which causes creatures touching it to be stuck to the mimic. Presumably until the glue was dissolved or the mimic destroyed.

Mimics also get an “ecology of…” treatment in Dragon Magazine #75, with a writeup by Ed Greenwood, who describes them as having eyespots (patches of sensitive, photoreceptive sensory organs) littered across its body, which is why direct sunlight blinds them.

The 2nd Edition Mimic is much more colorful–a bright, adventurer attracting red. These mimics have a little more detail to them. They aren’t just naturally occurring monsters, they have to be magically created with an outer carapace that protects them from whatever prey they encounter that might fight back. They come in two varieties, as before, common and killer–each does what it says on the tin.

2nd edition mimics are much bigger than their 1st edition counterparts, but otherwise are much the same as before, all the way down to their 3d4 pseudopod attack, and their adhesive glue that now has a little more clarity to its rules. You can dissolve it with alcohol, though only after three rounds, at which point you can try and pull yourself free. Otherwise, adventurers are stuck to the mimic while it pummels them.

However, despite the similarities between 1st and 2nd editions, the latter remains the most important edition to the development of the mimic for one reason:

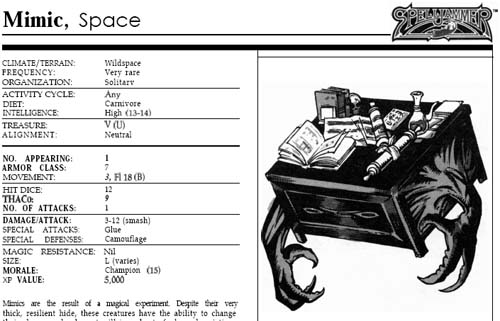

Space Mimics. Yup. Introduced in Spelljammer, these mimics could pose as patches of Wildspace, with their natural skin color appearing to be a shifting, twinkling cosmos. Or, failling that, they could appear as floating bits of debris, even ships (or parts of ships) that had been long abandoned, just waiting for an adventurer to claim them. They could also cast spells, were competent illusionists, and loved to eat wizards and take their stuff. I guess it’s true what they say–you are what you eat.

3rd Edition Mimics have a much more natural coloration. Their pseudopods are still mentioned in their description, though this illustration clearly shows two arms ready to make the characteristic slam attack that has come to define mimics for so long. It took until 3rd edition to categorize natural attacks that weren’t a bite or a claw as a slam–but it’s nice that they had that catchall.

These mimics are much less powerful though. The mechanics of D&D had started to become a little more forgiving, and it shows here in their adhesive ability. These no longer auto-catch you with their glue, instead there’s a DC 16 reflex save to avoid losing a weapon when you attack it. That said, the mimic did pick up a crush attack which it could use on any creatures that it was grappling–a feat made much easier thanks to its natural adhesive.

And at 1d8+4 that’s nothing to sneeze at.

4th Edition Mimics got a little off the rails. You had the same familiar mimic everyone knows and loves–called the Object Mimic in this edition. Only this mimic could adopt the form of any object OR alternatively could revert to its “native” form, that of an ooze, at which point it could do all the normal fun ooze things. Including slipping into spaces where it would otherwise be Squeezing without granting advantage.

However there was another kind of mimic–one that would impersonate the form of another sentient being, using its stolen form to kill and eat the next as it leaves a trail of bodies and different forms behind it. Which might sound an awful lot like the Doppelganger, but rest assured these are different, we promise.

The 5th Edition Mimic is a triumphant return to form. This artwork clearly knows what a mimic is and how it works. I feel like this is the best translation of concept to picture that we’ve had since 1st edition, which is saying something. As before, the Mimic is back to taking the shape of anything wood, stone, or other basic material, and they are known for generally taking the shapes of chests. And in 5th Edition these are represented mechanically with perfect imitation, as long as it remains motionless. As soon as it moves, the adhesive is deployed–and mimics are capable of snaring anything Huge or smaller with their glue. However it only takes a DC 13 to escape their grapple, so, apparently that glue has been fading in strength since 1977.

They do have the luxury of dealing damage AND adhesive with their pseudopod attack, though, which puts something in perfect position for its bite attack, eabling the mimic to deal piercing and acid damage at a staggering rate.

And that’s the mimic–a storied part of D&D history. They embody the “game” of it–they’re fun, but also deadly, but even when they show up you can’t feel too bad about fighting them because they’re just a chest. Or, my personal favorite, a door leading out of a room which had a chest (that turned out, of course, to be a second mimic).

They’re always fun to play around with, and have led to wonderful creations like the cottage-sized Elder Mimic, a BoLS favorite. So if you’re ever looking to get in the heads of your players–just turn back to this article, because it’s been a mimic this whole time.

Graaarrrarargh!