D&D: You’re Doing It Wrong – Five Rules No One Ever Remembers

D&D 5th Edition is the most streamlined, accessible version of D&D yet. Naturally we’re here to talk about all the ways people get it wrong.

It is no secret that D&D’s current ascendancy comes as a perfect storm of many things intersecting with one another: the cultural powerhouse that was Stranger Things, the rise of streamed games making them more accessible, and a general shift at D&D towards inclusivity, diversity, and above all else, accessibility. This is the game for new players with a lot of the imagination and creativity (and hooks) of the D&D of old as well. Veterans and newbies alike can find something fun in this game that’s especially easy to get into.

Even dogs!

Of course everyone’s doing it all wrong. Not in the ‘your particular style of play is wrong’ sense, but rather even in this most accessible edition of D&D there are still plenty of rules that people keep getting wrong, for a variety of reasons. They could simply not know they’re there–after all, one of the least read books is the Dungeon Master’s Guide, which probably has the rules for the thing you want to do in it already. And most players barely have time to game, let alone learn the rules for classes outside theirs.

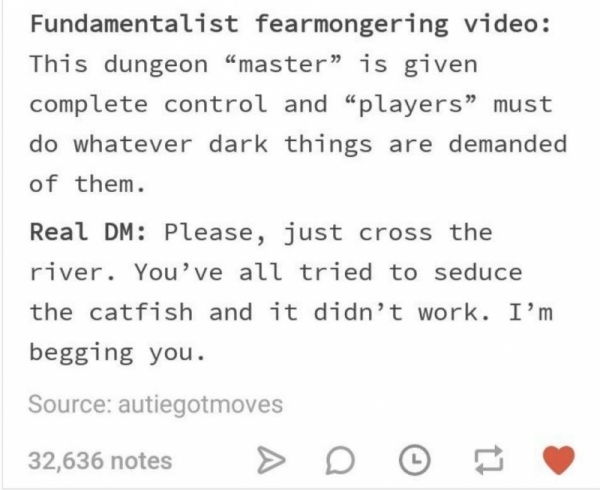

If you’re the DM? Good luck keeping track of everything, how could you possibly be expected to when you’re still just trying desperately to get your players to cross the river instead of trying to see if it’s trapped, because you saying “the river definitely isn’t trapped” is probably a trick to get them to cross, and they should go back to investigate that man who might have been attacked by a gazebo or possibly a davenport instead of continuing on with the adventure.

So it’s little wonder that there are all sorts of rules interactions that people just get wrong. And that’s what we’re here to look at today, some of the most-often mistaken rules and how they’re actually meant to play. With that in mind, let’s get right to it.

Surprise and Initiative

D&D fifth edition has been out for five years, and people still don’t know how surprise works. It’s understandable, considering that a lot of people still try to run it like it was in the good old days of 3.x edition, where you had a surprise round before normal initiative happened, and you had to spend ten minutes remembering features that meant that goblin didn’t hit you for 3 damage.

But Surprise is a tricky one in 5th Edition even without the added help from 3rd Edition baggage. That’s because it’s an abstraction that doesn’t necessarily reflect what you’re doing. I’ll explain that in just a second, but first here’s how surprise works in 5th Edition.

The DM determines who might be surprised. If neither side tries to be stealthy, they automatically notice each other. Otherwise, the DM compares the Dexterity (Stealth) checks of anyone hiding with the passive Wisdom (Perception) score of each creature on the opposing side. Any character or monster that doesn’t notice a threat is surprised at the start of the encounter.

If you’re surprised, you can’t move or take an action on your first turn of the combat, and you can’t take a reaction until that turn ends. A member of a group can be surprised even if the other members aren’t.

Alright, so far it’s pretty simple. The DM determines whether or not the two parties in a fight are aware of each other: if you fail to spot hidden attackers, you might be surprised. The thing that trips people up is that last little coda, which says you can’t move or take an action on your first turn of combat–the trick is just when that first turn happens.

In D&D, you roll initiative when hostilities start, even if there are people involved who aren't yet aware of those hostilities. The unaware creatures follow the rules on surprise. #DnD https://t.co/6zyk3egSFF

— Jeremy Crawford (@JeremyECrawford) October 2, 2019

Technically in D&D, you roll initiative as soon as hostilities start. So if you’re springing an ambush, you roll initiative. No free shot to start off the combat, you just go right into battle then and there. Again, this isn’t too bad either, but here’s where we get to the confusing part. The odd corner-case scenario where you might be springing an ambush, but because you rolled terrible initiative, you’re going last in the round, which means by the time it rolls around to you, nobody is surprised even though you haven’t attacked just yet.

There’s a little bit of dissonance in the idea that an unseen attacker faces a party who become aware they are under attack before their attackers have even had the chance to attack. But there you have it, initiative still matters–especially for characters like Assassins who rely on surprised enemies to get the most out of their abilities. There’s just something cool about a character rolling well and being ready to react to a danger they weren’t aware of.

Lighting/Visibility

Alright let’s talk lighting and visibility. This is one of those rules that can add a lot of atmosphere to an encounter, and can even amp up the tactical challenge, but it’s also hard to keep track of even if you’re using aids like a battle mat or notes about an encounter that say “this takes place in dim light” for theatre of the mind players. Ordinarily a light source sheds normal light out to a certain radius, dim light out beyond that, and then onto total darkness.

Still with me? Normal light is normal vision, no penalties. Dim lighting means that you take disadvantage on perception checks because the area is lightly obscured, and darkness is heavily obscured which means such checks automatically fail.

But hey let’s complicate this a little with Darkvision, which is something most parties are chock full of. You could be forgiven for thinking that Darkvisions means you see in the dark completely normally–or at least effectively. But Darkvision treats dim light as normal light, and darkness as dim lighting, so going torchless underground means everyone’s at disadvantage on perception rolls based on sight.

But we’re not done with visibility yet. Because dropping darkness (or any heavily obscuring spell effect) on unsuspecting foes is something a lot of folks do–only they probably don’t realize the rules about unseen targets and attackers. If you’re attacking a creature you can’t see, even one you can hear but not see, you have disadvantage. This cuts both ways, so if your target can’t see you, you have advantage when attacking them.

And now let’s complicate this with the way advantage and disadvantage function–they cancel each other out. So if you drop a darkness spell on a crowd of enemies, your targets can’t see you, so you have advantage! Which is great, except, you also can’t see your targets (without a few exceptions), so you have disadvantage to hit them.

Which means your spell has functionally not changed your die roll. Not to say there aren’t other effects, like enemy spellcasters can’t target you while you or they are heavily obscured, which is great.

One last visibility thing. Invisibility, the spell, which turns you Invisible the condition. Invisible creatures are impossible to see and count as heavily obscured in terms of hiding. But! Going invisible doesn’t mean your enemies don’t know where you are–this is a little detail with a huge impact. You can still be detected by tracks you leave and noise you make. According to the rules as they are written, if you turn invisible in the middle of a combat, unless you spend an action (or bonus action, rogues) to hide, your enemies can still attack you. With disadvantage, albeit, but they still can nonetheless.

Bonus Action Spells

There are two main misinterpretations when it comes to bonus actions and spells that you cast with them. Notably, some people have an impression that you can only cast one spell (with a spell level) per turn. Even the cast of Critical Role keeps saying this one–so take heart if you’re reading this, pobody’s nerfect. But you absolutely can cast more than one spell in a turn–as long as you have a way of taking more than one action in a turn. Fighters that can cast spells can use their Second Wind feature, for instance, to cast two fireballs on their turn, if they have that capability.

It’s just that most people can usually only cast two spells in a turn by relying on a bonus action spell–and that’s where it starts to get messy.

A spell cast with a Bonus Action is especially swift. You must use a Bonus Action on Your Turn to cast the spell, provided that you haven’t already taken a Bonus Action this turn. You can’t cast another spell during the same turn, except for a cantrip with a Casting Time of 1 action.

But even this still leaves people with a lot of little interactions that they get wrong. For instance, some cantrips like Magic Stone or Shillelagh are bonus action cantrips–as are any cantrips that a Sorcerer might Quicken (which lets you cast any spell as a bonus action). But even if you cast a cantrip as a bonus action, you can’t then use your normal action to cast a full spell.

So a Sorcerer can’t, say, quicken a fireball and cast a fireball. Or, if we’re talking cantrips, they can’t quicken something like Booming Blade and then use their action to cast fireball.

The way to think of it is, if you want to use your bonus action to cast a spell, the only other thing you can cast on your turn is a Cantrip.

Cover

Did you know that D&D has a system for determining cover? A lot of people don’t. This is because a lot of fights turn into boring melee-fests as fighters clump up and ranged casters try raining fire down. DMs, use more creatures with mobility and ranged attacks–seriously–but let’s get back to cover. There are three kinds:

A target with half cover has a +2 bonus to AC and Dexterity saving throws. A target has half cover if an obstacle blocks at least half of its body. The obstacle might be a low wall, a large piece of furniture, a narrow tree trunk, or a creature, whether that creature is an enemy or a friend.

A target with three-quarters cover has a +5 bonus to AC and Dexterity saving throws. A target has three-quarters cover if about three-quarters of it is covered by an obstacle. The obstacle might be a portcullis, an arrow slit, or a thick tree trunk.

A target with total cover can’t be targeted directly by an attack or a spell, although some spells can reach such a target by including it in an area of effect. A target has total cover if it is completely concealed by an obstacle.

Things worth noting: if a creature is between you and a target (friendly or enemy), they have half cover. You don’t run the risk of hitting your friends, but you do run the risk of missing altogether.

Also, speaking of ranged attacks, you don’t take a penalty for firing at a creature who is engaged in melee combat. Again, you don’t run the risk of hitting your friends if you’re shooting arrows into a melee. However, how many of you are taking disadvantage when casting a ranged attack spell or making a ranged attack while someone is engaging you in melee?

Concentration

Finally, Concentration. This one trips up a number of casters and is the bane of my existence. First there’s the restriction of only being able to maintain concentration on one spell at a time.

This one isn’t so bad–it’s just hard to keep track of if you’re not used to it/don’t know which spells are concentration spells. It gets tricker when you realize that a lot of spells require concentration and if you cast another spell that requires concentration, even if you don’t maintain concentration on it, the spell you were concentrating on ends immediately.

You might be wondering about Concentration Checks–well those aren’t a thing anymore. Another holdover term from 3rd Edition. Concentration might be disrupted if you take damage–and that means making a Constitution Saving Throw:

Whenever you take damage while you are concentrating on a spell, you must make a Constitution saving throw to maintain your Concentration. The DC equals 10 or half the damage you take, whichever number is higher. If you take damage from multiple sources, such as an arrow and a dragon’s breath, you make a separate saving throw for each source of damage.

Finally a DM might decide something particularly hazardous, like fighting on a ship tossed by a storm, or fighting in the midst of a blizzard, or any other hazard might require you to make a Constitution save of DC 10 or lose concentration.

Phew, that’s a lot of rules. Let’s turn it over to you: how many of these were you getting wrong? How many are you getting right? What rules are your achilles heels? Let us know in the comments!