How D&D Shaped The Video Games You Enjoy Today – PRIME

Well before D&D even flirted with digital dungeon delves, it was influencing video games the world over, with a legacy that carries through to today.

Introducing new players to D&D is easier than it ever has been, thanks in part to the massive blossoming of fantasy onto the public consciousness. For one, these days D&D is everywhere, from the New York Times and USA Today, to the Guardian and Forbes–but that only gets you so far. Sure, everyone’s heard of D&D, but what does that really mean? Well there’s an easy answer for that too–“it’s a bit like World of Warcraft” or “did you ever play Dragon Age?” There’s a whole medium that can stand in for explaining what D&D is kind of like. Picking out a class? Well that’s kinda like picking out a job in Final Fantasy, or picking a character in Diablo III. Spell slots are basically mana, and everyone knows what a hit point is when you say ‘your health’. Video games have made it incredibly easy to explain D&D, but that’s because an astounding number of them have been shaped, foundationally, by D&D.

I’d go so far as to say if you’ve played a game in the last ten years or so, you’re connected to the DNA of D&D. It all comes back to those heady, halcyon days of the 1970s and 80s, when computers–and D&D–were just beginning to really take off. Now before we get in too deep, sure, there are some obvious D&D games, but we’re going back further than that. In order to understand where D&D begins to influence the industry we need to look back at the beginning of both of these industries. If you’re interested in the Rise and Fall of TSR (which is also the rise and fall of D&D before it’s meteoric rise) you can learn more in some of our earlier articles. Here’s a brief overview though.

Big Things Have Small Beginnings

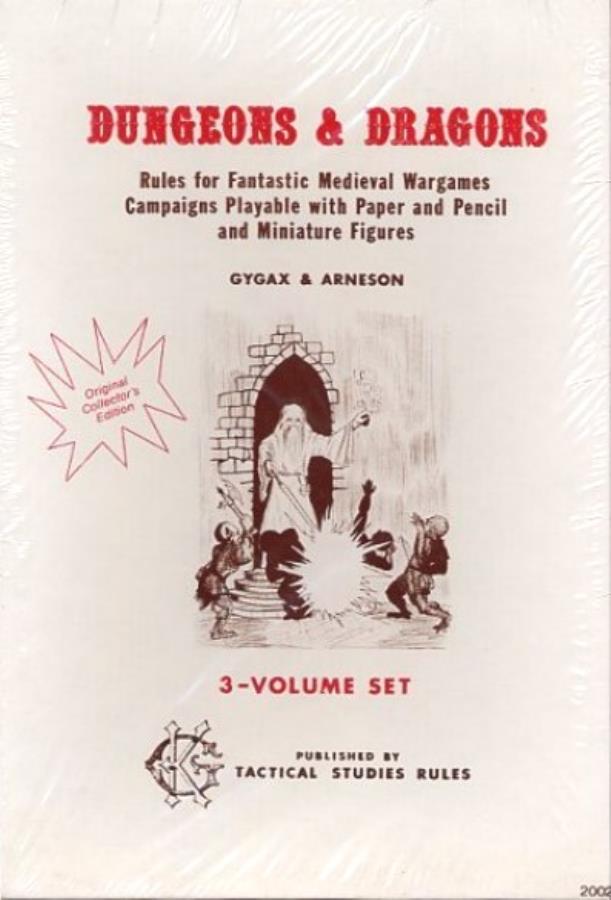

TSR began in Lake Geneva Wisconsin after wargaming enthusiasts Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax participated in a proto-RPG called a Brownstone that was part LARP, part RPG scenario, part wargame where players would take on the roles of characters in a fictional town during a Napoleonic era battle. These infamous events brought together hobbyists and together Gygax and Arneson cooked up D&D, which blended the idea of a fantasy wargame with playing individual characters. For the first few years, the game sold like hotcakes, quickly spreading throughout the world, including overseas where a company called Games Workshop would go on to distribute the game throughout the UK and eventually making its way around the world, including Japan in a big way in 1986, but we’ll get into that in a minute.

While all of this is happening, video games are on an even more meteoric rise. Two years before D&D was first published, Atari, inc. was due to publish Pong, which is widely considered the first commercially successful video game, and home consoles like the Magnavox Odyssey were bringing video games to a much wider audience. Video games were coming into their own first rush, and would soon see their own market flooded, alongside a devastating crash in 1977–a heavy lesson that TSR could have learned from for they fell prey to basically the same thing almost a decade later. But for now, games are booming. Even before the release of arcade cabinets, though, video games had their home on mainframe computers, and in particular at universities.

Spacewar! is the first example of a mainframe computer game. In it players are pit against one another as starfighters flying through space obeying a rough approximation of Newtonian physics, armed with a limited number of torpedos and the goal of blowing up the other person. The proliferation of games like this is important, because it helps make for rich, fertile ground when D&D comes along. The two industries intersect well before anyone realized how big either of them would be. And the first known place is in a game called pedit5.

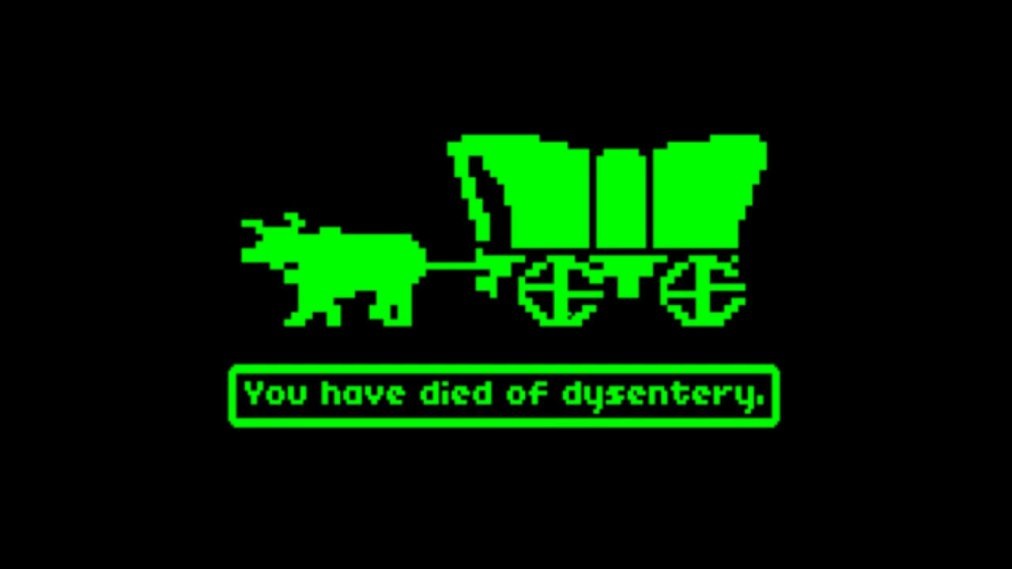

pedit5 is believed to be the first example of a D&D-inspired video game. The whole thing is a top-down dungeon crawl, where players would generate a character with statistics inspired by D&D statistics like strength and dexterity and hit points, and explore a single-level dungeon where they could encounter randomly generated monsters, and acquire treasure, kill monsters, and cast spells.

The dungeon itself was a persistent layout–the rooms were always the same, but the contents, monsters and treasure, were created at random, making this a proto-roguelike game. More on Rogue in a minute, though. pedit5 is a story all itself. For one, the name comes from the naming convention of the University of Illinois’ Population and Energy Group program slots:

The earliest surviving role-playing game on the PLATO is pedit5, alternately called The Dungeon, written in 1975 by Rusty Rutherford. Rutherford worked for the Population and Energy Group at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, and his group was assigned pedit1 through pedit5. Pedit1 through pedit3 were programs for the Population and Energy Group, which left two surplus spots for additional usage. The game was frequently deleted, as the system administrators determined that gameplay was an inappropriate use of this space. An earlier game, m199h, appears in some PLATO lesson lists, but descriptions of this program sound more like text-based Adventure type game than a dungeon crawl.

And though sysadmins would delete the game wherever they found it, the game–and others like it–spread pretty rapidly.

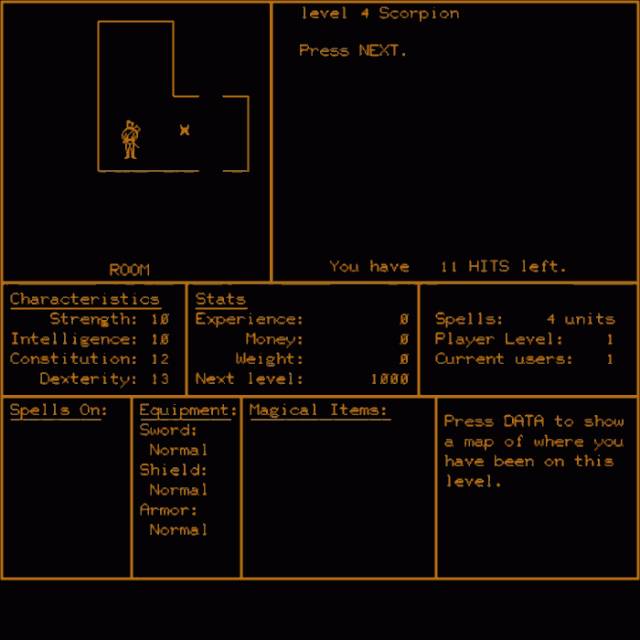

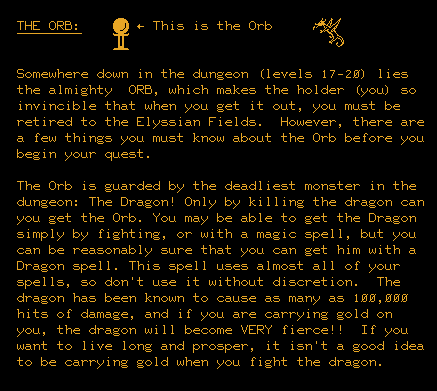

Another, much more obvious example can be found in the game dnd, which takes its name from Dungeons and Dragons. Developed by Gary Wisenhunt and Ray Wood while they were at Southern Illinois University, dnd was a game inspired by pedit5, but with new features, many of which are still around in video games today, no matter their genre:

As we built the game we added new features that we didn’t see in other games, such as the Orb, transporters, the idea of a boss monster (there was no term for that since there wasn’t anything remotely like that at the time, we just wanted a final challenge against a very powerful opponent before you could “win” the game and have your character retired to the Elysian Fields).

At the time, though, one of the most powerful features was probably the fact that Wisenhunt and Wood were sysadmins of the main frame, so they didn’t have to worry about their game getting deleted, a fact which meant it was around when the game’s other big author, Dirk Pellett came to the university and played both D&D and dnd and loved the latter so much he made improvements:

Dirk Pellett had also played D&D at Caltech in 1974 and 1975, before coming to Iowa State University. He played dnd, and liked the game so much that he had ideas for improving it. He made his suggestions to the original authors, Gary Whisenhunt and Ray Wood. They liked his ideas enough to give him access to edit the game directly, and he joined them as a full-fledged author of the game. By October 30th, 1976, Dirk had added many enhancements, including a great variety of magic items and more monster types. Within 21 months of the publication of the D&D rule book, the game of dnd based on it had reached version 2.8, and a counter of the number of dungeon trips by all players since the game’s creation (or, at least, since the counter was initialized) was fast approaching the 100,000th trip.

For those of you playing along at home, this means that within a scant 21 months of the game D&D being published, it helped influence and standardize the creation of video game tropes so common that you don’t even think of them as tropes–they’re just a part of the genre. It’s hard to imagine most video games without boss encounters, or main, overarching quests. But even things like random battles and charmed monsters that fight for you (aka pets), have their origins with D&D.

Even if the game you’re playing has nothing at all to do with dungeons and/or dragons, you’d be hard pressed to find a game that didn’t feature “health” or “life” or some kind of leveling up? Even your first-person shooters have embraced the inevitable gamification and you can get yelled at by a fourteen year old somewhere in middle America who’s still struggling to learn how to curse well–but makes up for a lack of understanding with an unbridled enthusiasm–while grinding enough XP to gain your next level in a CoD or a Battlefront.

Not that D&D invented the idea of ‘a progression system’ but it helped codify it in the minds of the early generation of players who would go on to become the early generation of game designers. Those roots, like those of the trees outside of Isengard, go deep.

Down Into the Dungeon

Even the term ‘experience points’ comes from D&D. Well, if you want to get pedantic and who doesn’t, it comes from Dave Arneson’s proto-RPG Blackmoor, which in many respects we are worse off for not seeing how that game might have further influenced RPGs if Gygax hadn’t been so quick to sideline Arneson and take over D&D in the 80s. Blackmoor is the first game to feature experience points and leveling up, though they migrated over and gained popularity in D&D.

Even format stuff, like taking control of a whole party of characters has its origins with D&D. Though dnd was all about a single character, another game, Dungeon, would take on multi-character parties.

Dungeon was an unlicensed adaptation of D&D written by Don Daglow, a student at the Claremont University Center:

“In the mid-seventies I had a fully functioning fantasy role-playing game on the PDP-10, with both ranged and melee combat, lines of sight, auto-mapping and NPC’s with discrete AI.”

And while it’s hard to track down a game called Dungeon, you can find traces of it. The game was mostly a text-based game, though it did have some graphics elements to help portray line of sight. Most importantly, though, it allowed you to take command of a party of characters. That would help lay the foundation for the next wave of games that more closely resembles what we consider modern cRPGs. But before we go there, there are a few other branches to explore.

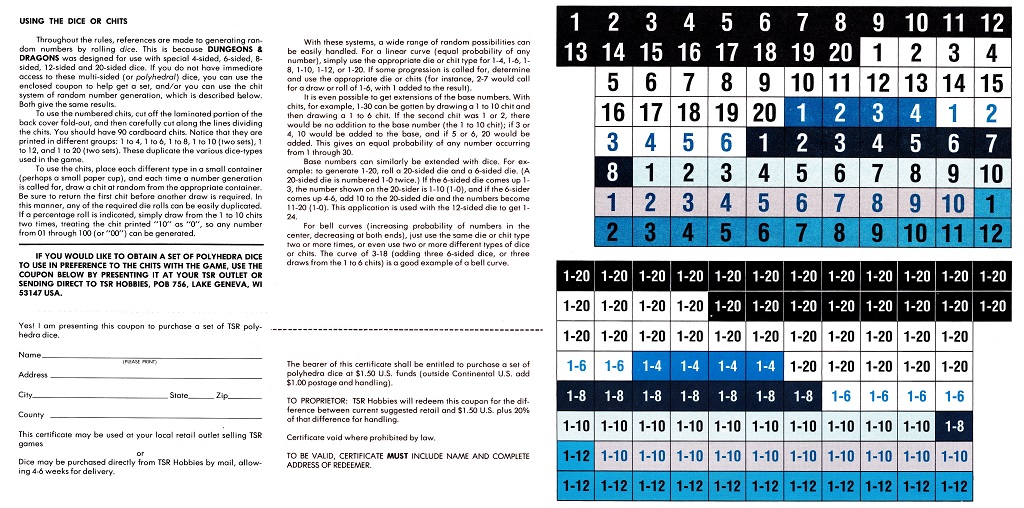

The games we’ve listed so far are right around the launch of D&D. Gygax and Arneson’s game was a hit with the people that loved it. So much so that the game’s 3 volume set, which went for a cool $10 in 1970s money, which equates to about $52.17 today, had to be reprinted. There was even a run on dice for a while, and some versions of the game came with a sheet of perforated number chits that you would draw, because the folks that D&D found to manufacture their polyhedral dice weren’t prepared for the demands of hungry gamers.

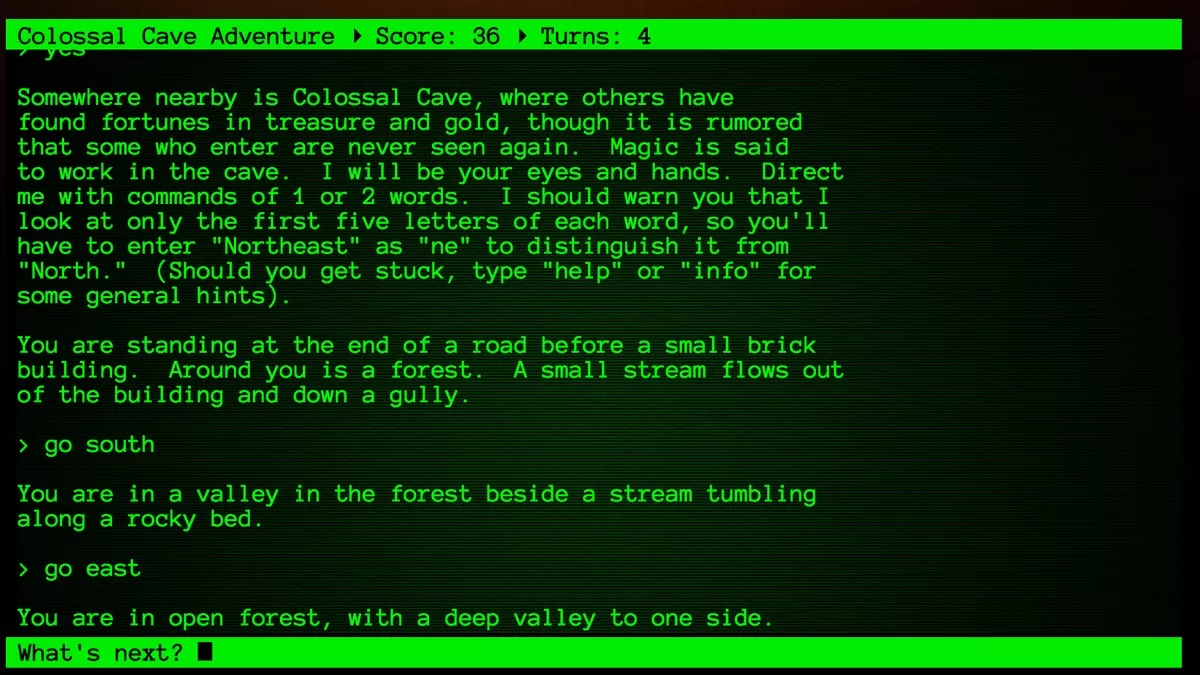

To be fair though, TSR did manage to get their act together and make sure there were dice enough for all. But the point is the runaway success of early D&D took people by storm. The people that played it wanted to share it with their friends and families. Which takes us to another early game, Colossal Cave Adventure, or as it was sometimes called Adventure. This game is one of the early text games, developed by Will Crowther in 1976. Crowther, then a student at Stanford and an avid caver, wanted to share his love of D&D and caving with his estranged daughters. And to do that he created a game about exploring a cave with fantasy/D&D elements sprinkled in:

Colossal Cave is certainly a groundbreaking game, both in the figurative and literal sense—the author and his wife were dedicated cavers, and Crowther based much of the game on an actual cave system in Kentucky.

AdvertisementSurely it is not a coincidence that both games are focused on the type of thrilling exploration one finds as a caver or urban explorer. To my mind, these games are less “interactive novels” than “interactive maps”. Another interesting “coincidence” here is that the first jigsaw puzzle ever sold was of a map. It seems that maps and puzzles have been associated from very early times!

Although exploration games can be rendered with graphics instead of text, this eliminates much of the freedom (or at least the illusion of such) allowed by text.

That’s right, we’re in text-based territory now. Colossal Cave Adventure is one of the earliest interactive fiction games. But if you drill down, text based games like Colossal Cave Adventure or Zork are essentially just a simulation of the conversation between player and dungeon master in D&D. Especially when you take into account Crowther’s desire to adapt D&D:

I had been involved in a non-computer role-playing game called Dungeons and Dragons at the time, and also I had been actively exploring in caves – Mammoth Cave in Kentucky in particular. Suddenly, I got involved in a divorce, and that left me a bit pulled apart in various ways. In particular I was missing my kids. Also the caving had stopped, because that had become awkward, so I decided I would fool around and write a program that was a re-creation in fantasy of my caving, and also would be a game for the kids, and perhaps some aspects of the Dungeons and Dragons that I had been playing. My idea was that it would be a computer game that would not be intimidating to non-computer people, and that was one of the reasons why I made it so that the player directs the game with natural language input, instead of more standardized commands. My kids thought it was a lot of fun.

Text adventure games like this emulate the way a DM describes what’s going on in the world of the game. Instead of a human sitting across the table from you, telling you that the small stone room smells of old hay, or that obvious exits are West, East, and Dennis, the computer sets up the prompts instead. It then waits patiently for the player to give a response of what they want to do, and then it interprets it. Often with unexpected results–a famous example of this comes from Colossal Cave Adventure’s encounter with a dragon:

PLAYER: kill dragon

COMPUTER: With what? Your bare hands?

PLAYER: yes

COMPUTER: Congratulations! You have just vanquished the dragon with your bare hands! (Unbelievable, isn’t it)

You can practically hear the DM and players laughing about this. There’s very much a conversational style to these kinds of games. And it comes from D&D. In fact, it comes from a variant D&D that was developed around 1975 by Eric Roberts, called The Mirkwood Tales. Crowther would take the experience of the Mirkwood Tales and combine it with the experience of exploring the Mammoth Caves of Kentucky to create the Colossal Cave Adventure.

REFEREE: The passage continues west.

FARIN: We’ll follow it.

REFEREE: After walking about twenty more feet, you notice that there is a corridor off to the north some twenty feet ahead of you, although the main passage continues west.

FARIN: We go up to the intersection and carefully look into the northern corridor. What do we see?

That’s a transcript from Roberts’ Mirkwood Tales manual. But it could easily be a segment from an adventure game. Just replace ‘we’ll follow it’ with ‘go west’ and add in the occasional ‘look’ and you have all the elements of an adventure game. And if any of this is sounding a bit like Zork, well you’d be right. For context, Crowther was more than just a caver and a D&D enthusiast. He was also part of the original ARPAnet team, and is responsible for the internet evolving into the platform that we’re all on today.

Naturally word of the game got around. Other programmers played the game–which was designed to be accessible by non-computer people–and they loved it. There’s an urban legend that people were so drawn into the mystery that all computer research in the country ground to a standstill for two weeks while people tried to play through the Adventure.

For a couple of weeks, dozens of people were playing the game and feeding each other clues … Everyone was asking you in the hallway if you had gotten past the snake yet.

Enter Zork…

And true to form, they beat the game by examining the game with a debugger. But once Colossal Cave Adventure was done, they wanted more. So a team of four authors, members of the MIT Dynamic Modelling group, Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling came together and wrote Zork, first developing their own command language parser that would lay the foundation for the Great Underground Empire. They took Crowther’s original design and expanded it in every direction. They had added considerable more elements of fantasy to the game, including the troll and cyclops and thief.

Zork was a bigger game than adventure. With a completely new map and more puzzles to work their way through, as well as familiar elements like an inventory and combat that required the right kind of items to succeed (if you were lucky), Zork was a hit. And when the developers finally finished it in 1978, they named it Dungeon, and watched as it became popular among gamers. And here, we get to another important part of the influence that D&D has had on gamers.

1978 is a particularly litigious year for TSR. This is around the same time the company is establishing its own headquarters, and stretching out its legal muscles. Now, this is in part because around ’78 and ’79 there were many D&D copycats like Tunnels and Trolls, and the common response from TSR was to send a cease and desist, which they absolutely would back up with a lawsuit if needed. Though they wouldn’t earn the name until later, a popular joke held that TSR stood for They Sue Regularly.

And it’s this litigious spirit that has influenced Zork, because when TSR got wind of Dungeon’s popularity, they responded the way you’d expect. As Tim Anderson puts it:

“Zork was originally called Zork. It was renamed to Dungeon in a fit of tastelessness later on, then renamed back in response to a threatening letter from the D&D guy’s lawyers. I found the response from MIT’s lawyers extremely entertaining, but I don’t think anyone wanted to fight for the right to use a bad name.”

Only the Beginning

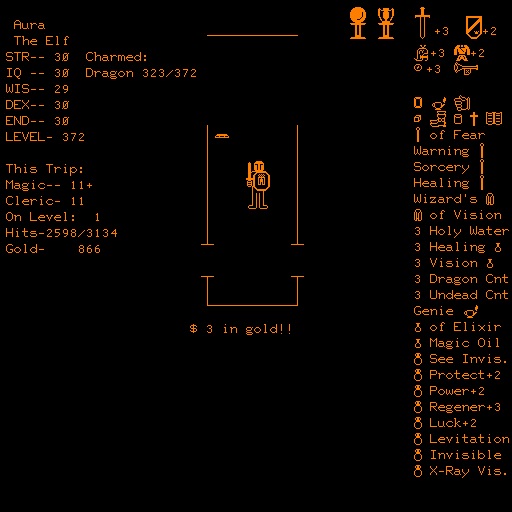

But this is only the very beginning of D&D’s influence on the development of video games. The biggest steps, which would see not only the number crunch and puzzle-solving elements of D&D, but the story and the roleplaying part of a roleplaying game get implemented into computer games, would come just a few years later in the early 80s. Games like Ultima and Wizardry wore their influences on their sleeves, and would be responsible for carrying D&D much further than the original three volume set.

That’s a story for another time though. Check back for part two!