RPG: Star Frontiers – A Game Ahead Of Its Time – Prime

Though Dungeons & Dragons put them on the map, TSR was one of the biggest RPG producers in its day. Here’s a look at their most underrated system, Star Frontiers.

Star Frontiers is the sci-fi RPG of your dreams, even if you’ve never played it. Created during the heyday of TSR’s dalliance with genres beyond fantasy on their quest to make themselves the single best name in RPGs, Star Frontiers is the lovechild of classic 70s Sci-Fi titles, like Battlestar Galactica, Buck Rogers, and a certain movie about a farm kid from Tattooine–and a team of RPG designers who were given a surprisingly free rein to create something that felt like it leapt off of the screen or the page, and into your imagination. In an era when many of the ‘aliens’ you could play were humans with different foreheads, Star Frontiers got weird. It delved into weird questions that all the best sci-fi explored, and then, just when it was bursting onto the scene, it was killed.

It was a game ahead of its time, and one that ignited the flames of sci-fi in many a young gamer. With its flexible system, and, for TSR, bold new classless system, Star Frontiers is a one-of-a-kind jaunt into a world like no other. Come and join us today as we step back through history and take a look at the utter madness and glory that is Star Frontiers.

First let’s set the stage for the birth of Star Frontiers. Now while this is D&D’s first committed outing into stellar adventures, science fiction had been a part of TSR’s very roots. As early as 1975, TSR had been peppering sci-fi elements into their most popular game. Let’s look at the revolutionary Blackmoor supplement, which included an adventure The Temple of the Frog wherein players must rescue a captive baroness from an evil temple. This is the first adventure designed for other people to run–which makes it remarkable, but moreso because it features many science fiction elements, like power armor, teleporters, and “scout craft.”

The High Priest of the Temple of the Frog.

Traditionally this role was voted to the most influential member of the “Inner Circle” of the brothers. It is now held by a usurper, Stephen the Rock. This fellow is not from the world of Blackmoor at all, but rather he is an intelligent humanoid from another world/dimension. Originally, he and his compatriots were sent to the area to police it against incursions of similar beings, for it was discovered that a dimensional nexus point existed in this area that allowed such possibilities. He assumed leadership of the Temple in order to have a base of power, for he now seeks gory and personal gain, with as little personal risk as possible. When the team was intact, this self-seeking would have been checked, but with the death of all but the creature now posing as the commander of the guards, loyal to the High Priest and also power-oriented, most restraints are gone.

Once each year the High Priest must report to a hovering satellite station, giving the details of what has transpired below, and turning over any powerful “artifacts” taken during the previous time period. Failure to turn over sufficient loot will certainly result in his recall/trial/extinction — as will, in fact, the discovery of just what has been going on below!

At present the High Priest possesses a complete set of battle armor, a mobile medical kit, and a communications module. He has modified the Temple so that there is a complete set of alarms to warn of intruders and established identification rings to allow him to direct and control all movement. He has genetically modified the killer frogs to begin breeding frogmen and constructed the control ring to maintain his control ability over them. Other treasure have been brought to him and he has mastered their uses. Other treasures have been brought to him and he has mastered their uses. He has no magical abilities of his own but when in the battle armor he is immune to many things.

Advertisement

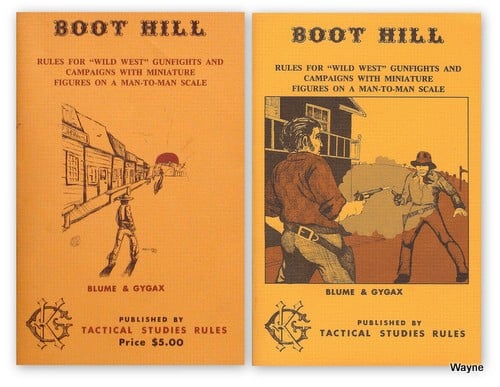

And the list goes on. The Battle Armor is straight up a suit of power armor. Later they’d add anti matter rifles, and so on–but 1975 was an excellent year for TSR. It was also the year the third RPG was introduced: Boot Hill, an RPG of the Wild West.

Over the next few years, D&D supplements would give TSR a chance to grow massively. The next five years saw D&D Coalesce into AD&D, as well as exploring other genres and other games. 1980 ended with TSR reporting $20 million in gross sales by the end of 1981, just to give you an idea of how rapidly the company was growing.

And on the way there they had explored all but the most obvious ground. By the time Star Frontiers rolls around, we’ve seen Boot Hill, Gamma World (post-apocalyptic) and Top Secret (an espionage RPG), even an RPG set in the roaring 20s called GangBusters. But Sci-Fi didn’t have much. There was Traveller, introduced in 1977, and that system was fantastic if technically complex. Traveller was a great system for playing Hard Sci-Fi. Which is great, if that’s what you’re after.

But 1st Edition Traveller was… challenging. To the point that when Star Frontiers finally came out, it was marketed as ‘The Playable One’.

And it’s onto this fertile ground, not five years after Star Wars came along and changed everything, that Star Frontiers erupts. Perhaps the best thing it had going for it was its playability. Star Frontiers, especially the earliest edition was about as basic as it gets. Echoing the earliest days of D&D, Star Frontiers gave you rules for moving tiles and tokens around on a map and determining combat stats and attacks and the like.

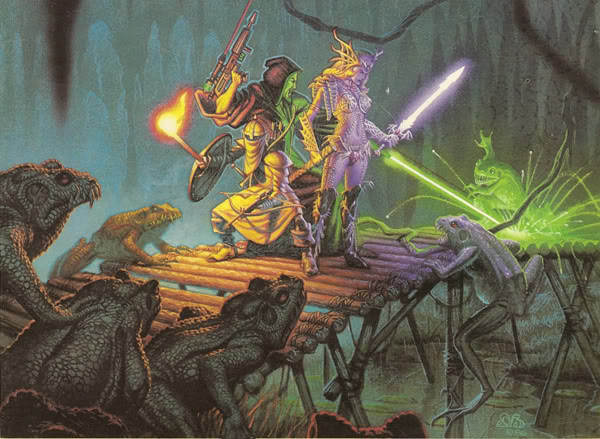

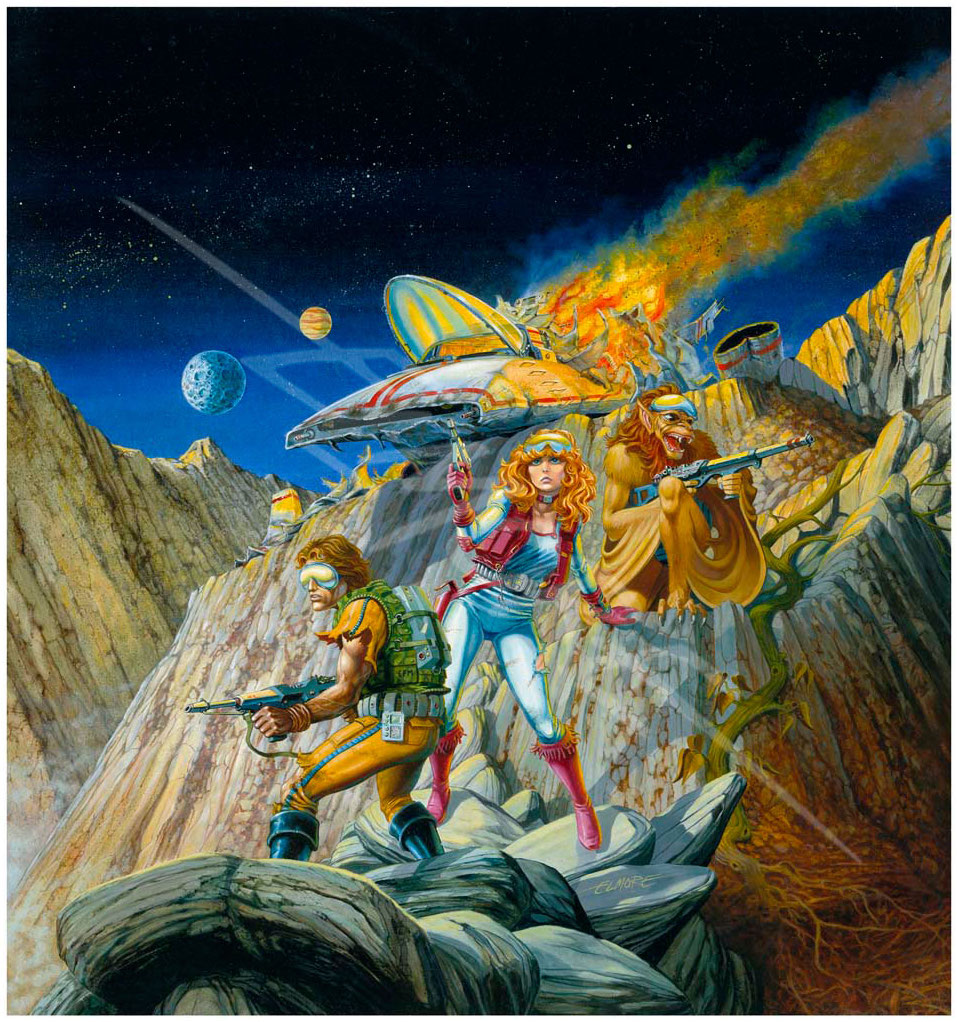

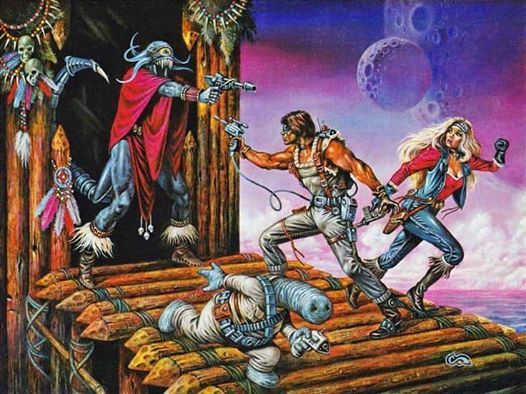

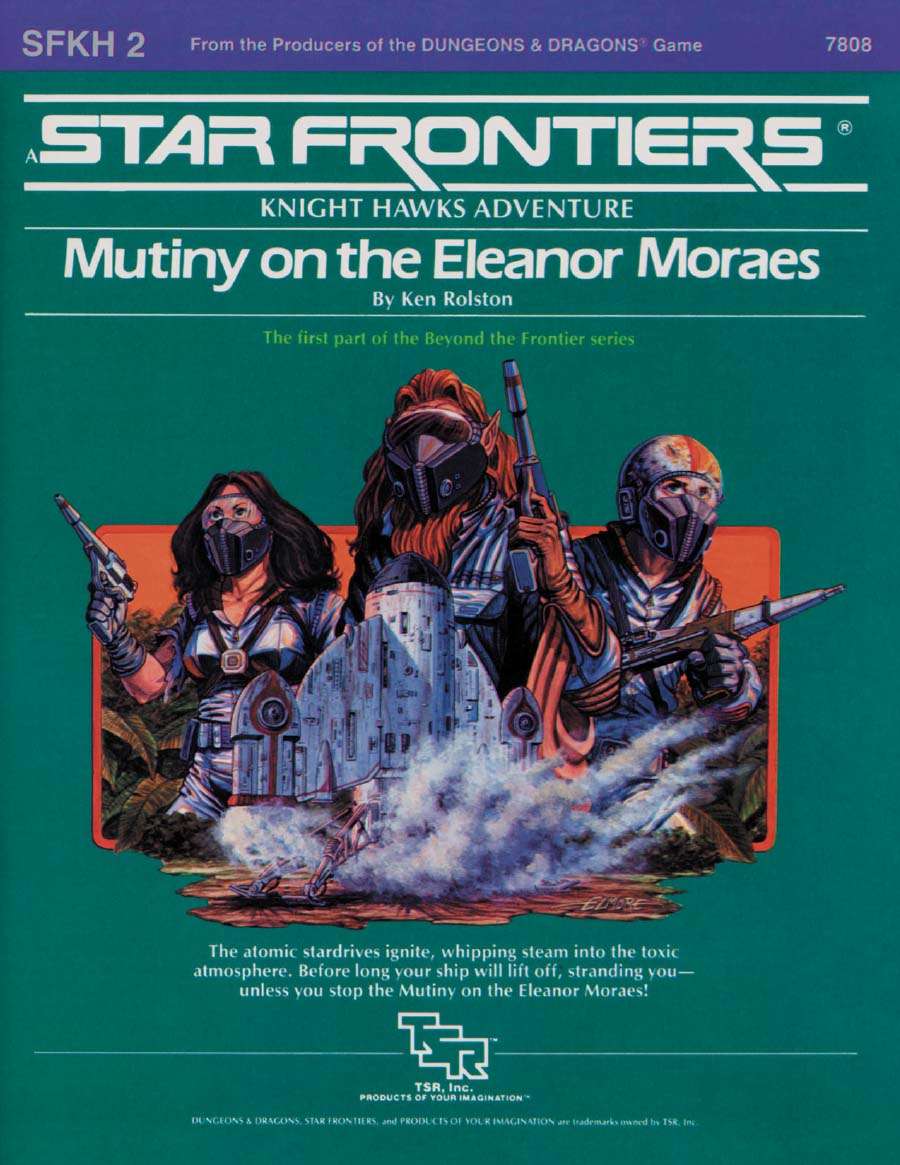

But the other big thing it had going for it was its skill system. Well. Okay that’s not true. The single best thing it has going for it is Larry Elmore’s art at the peak of his ability. You will not find better art out there for a sci-fi game. It’s as gloriously 80s as it gets.

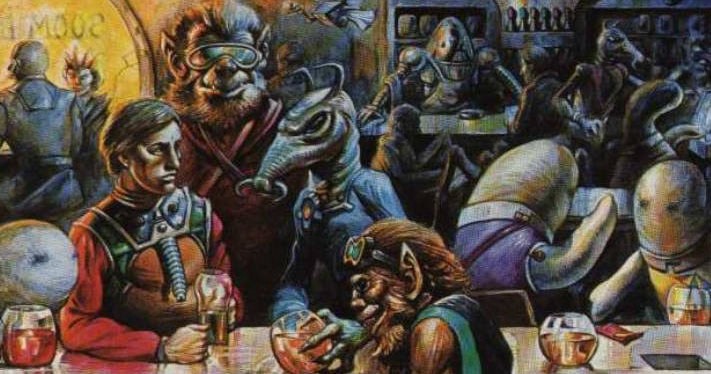

Even the cool bat-man has sunglasses. It’s a theme that repeats itself consistently. And Larry Elmore outdoes himself every time. He captures the feeling of the game, so that even without reading the rules you can get what it’s going for. This isn’t the pristine sci-fi of Star Trek. It’s sci-fi with swashbuckling and sunglasses. It’s all about laser guns and daring escapes and harrowing crashes. It’s not the time to worry about oxygen scrubbing, but about whether you have enough ammo left to deal with the aliens that are coming your way.

The first edition of Star Frontiers reads very much like a gunslingers in space kind of game–in the basic rules, the game is set in an area known as “The Frontier Sector,” they’re tasked with exploring the Frontier, looking for evil aliens and adventure. As later expansions were released, the game changed, but for now let’s look at some of the basic rules.

The basic game is centered entirely around its stats. There are eight all in all, paired into four distinct pools: Strength/Stamina, Intuition/Logic, Dexterity/Reaction Speed, and Personality/Leadership. They pretty much do exactly what they say on the tin. It’s nothing truly remarkable, roll a percentile dice to determine a base score from 30-70, and the rest of the game is all about rolling under your strength score with percentile dice.

And that’s it. The rest is about getting equipment, and the like. But where the game really takes off is with the Advanced Rules.

These rules add more detailed explanations of character abilities, new rules for movement and combat, new equipment, and rules that would allow characters to advance and learn skills. Basically this expansion added the roleplaying portion of the roleplaying game–including rules for someone to run the game as the referee.

As we mentioned, this is where the game takes off. You still use all the same percentile dice and eight abilities, but the expanded rules mix in experience points and most importantly skills. Here’s where the game departs from the ‘wild west gunfights in space’ formula and comes into its own. Take a look at the skills offered in the game, and you’ll find some quite complex rules for interpreting what they can do.

A player character might learn the Computer Skill but within that skill’s umbrella, there’s a lot to pick from. You might write programs on the fly, defeat or bypass security, get relevant information to display, manipulate programs, repair or interface with strange computers. Each of these subsystems has its own order of operations to go through that sets out very clear guidelines for what characters can and can’t do.

For 1982, this is groundbreaking. In contrast, Oriental Adventures won’t release until 1985, and it’s not until then that the idea of nonweapon proficiencies are introduced, and the idea of what we think of as “skills in D&D” lays its groundwork. It starts with Star Frontiers.

The other thing that helps Star Frontiers stand out from the crowd is its boldness. As previously mentioned, the early 80s were a fine time for TSR. The rumblings of Gygax’ ouster from the company are a few years off yet, and despite layoffs and financial troubles, by and large the company is able to keep itself going by releasing products for a hungry audience.

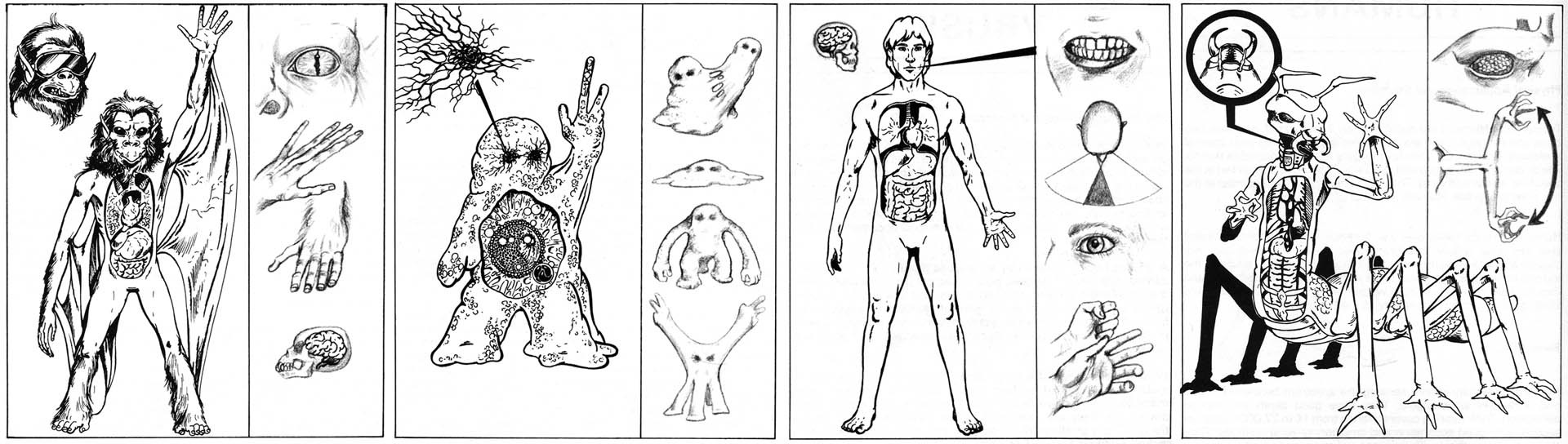

And with Star Frontiers, the TSR staff takes a huge swing. Take a look at the alien races available to players. They’re a far cry from what you see in other Sci-Fi RPGs. While there are only four to pick from, they stand out.

There are the standard humans, which everyone knows and is. But players could also choose to play one of the amoebic Dralasites. These short, rubbery aliens have no bones or hard body parts–instead they have a tough, flexible membrane that protects their central nervous system, keeping their internal organs floating inside themselves. It’s said that if you look closely you can watch a Dralasite eating by absorbing its food directly through its skin.

These aliens are reminiscent of the Herculoids, but get some distinct personality traits. They love to take steam baths, get into debates, and love old jokes and puns “that make Humans groan,” to the point where it’s canon that failed standup comedians can go on to found massive success on Dralasite worlds. Which explains Dane Cook, for instance.

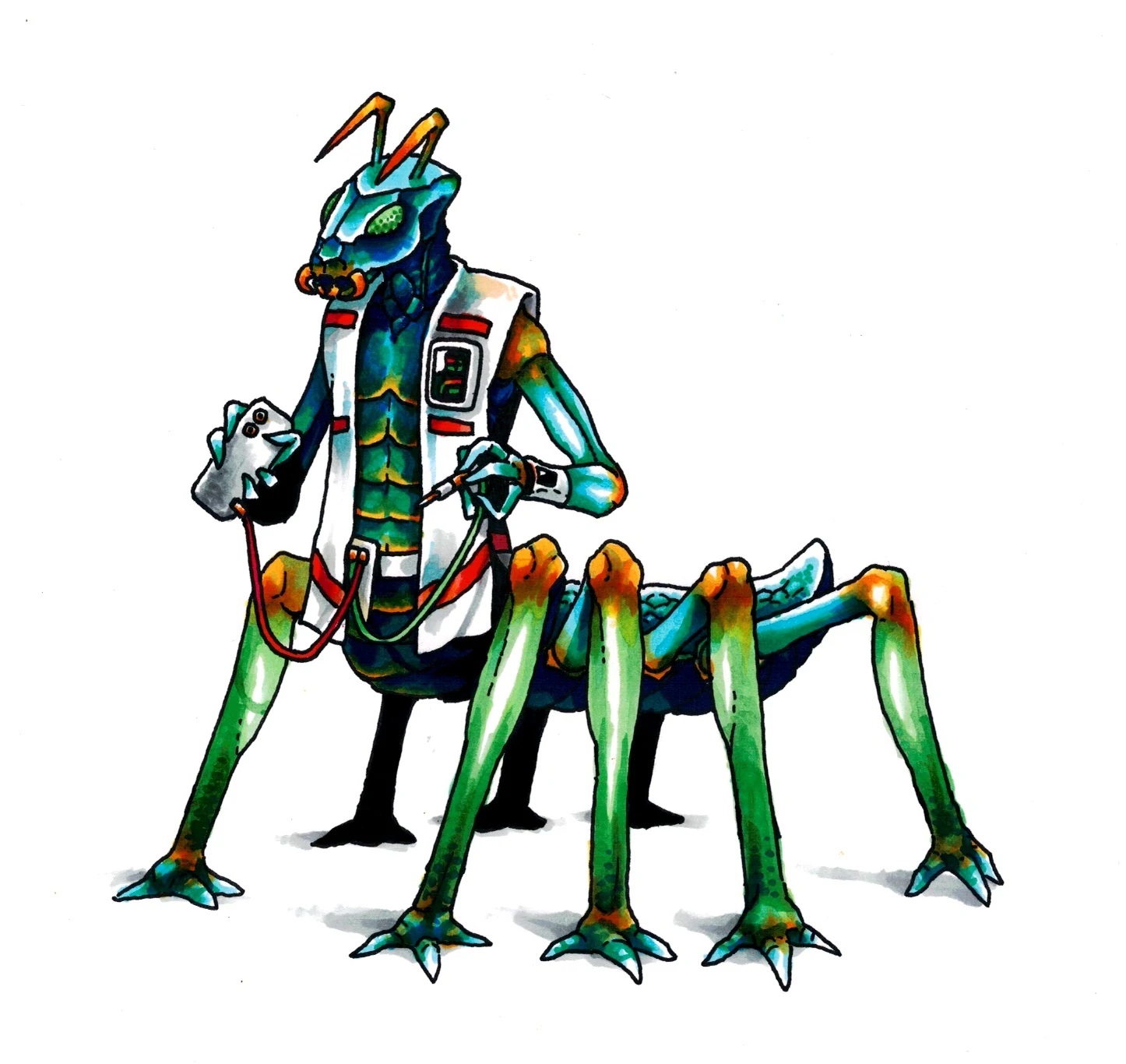

The mantisoid Vrusk on the other hand are a curious mix of Vulcan and Ferengi. They are practical and driven by an analytical love of harmony and order. But their main motivation is to get rich enough to buy whatever they want, and then peace out of society so that they can continue making money without taking risks.

Finally the Yazirians are a strange mix of bat and ape–they have leathery membranes that give them the ability to glide, and they share many traits with your typical honorable warrior race, except for that they’re all typically a little more frail and lithe than big and beefy. It makes for interesting roleplay choices.

Opposing all of these are the Sathar. These are the enemy of all life–long worm-like creatures who try to kill every alien creature they meet on the Frontier. They refuse any attempts to communicate, instead preferring to attack and, if overwhelmed, will kill themselves rather than be captured alive. And it’s hard to beat one–they come eqiupped with hypnotic powers, advanced technology, and their agents spread their influence like a virus. There’s a reason most Star Frontier players will tell you all Sathar must die.

The Expanded Rules introduce a lot. If you want to know how to create your own alien creatures, they give you some of the best advice for making your own aliens/monsters, including “what does this creature do and why are you making it.”

For all that though, the real next-level in game design comes one year later, with the advent of Knight Hawks. This is the spaceship ruleset for Star Frontiers, and it’s honestly some of the best ship-to-ship combat that would hit the market for quite some time.

There’s a wonderfully usable system for creating your own starship that focuses on how the players will play with their ships. It gives you the parts you’ll need to use to start having exciting ship battles. Starship decks are stacked on top of each other, giving you a very modern starship layout (compared to other sci-fi games at the time that ran everything horizontally, look it was a weird time).

While these aren’t as in-depth as more vehicle-heavy systems, the mechanics presented in Knight Hawks are a logical extension of the system introduced in the core books. And Knight Hawks goes beyond just creating ships and battling them. It talks about other things you might do with them, including mortgaing them, using them for business purposes, mining with them–it’s very reminiscent of the infrastructure you see in place in games like EvE Online or Elite Dangerous, where you can easily find many types of ships operating in a way that feels realistic, but still fun.

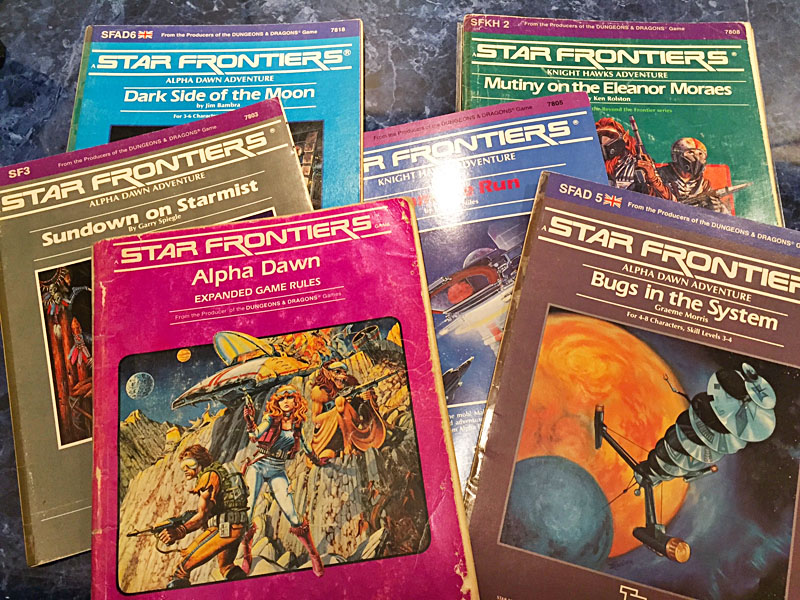

And that’s saying nothing of the modules that were released. Star Frontiers was basically its own community in the RPG world for a while. There were some truly excellent modules released, along with some truly mediocre ones. Many players pan the first adventure module, Crash on Volturnus because it’s about as railroady as you can get without being in Promontory Utah. You know, where the transcontinental railroad was finished.

The biggest problem this one has is it’s a wilderness adventure in a space game. Players didn’t want to feel like they were space boy scouts, they wanted to feel like space heroes. Like something straight out of Buck Rogers. Which is where modules like the Mutiny on the Eleanor Moraes shine.

In Mutiny on the Eleanor Moraes, players are part of an exploration vessel given the task of surveying a distant star system. While conducting operations, the ship’s first officer engineers a robotic mutiny, attacking an airship and sending the crew careening to the ground. Players start off receiving a message from Bill Terry (as 70s sci-fi a name as you can get):

I directed the survey robot’s attack on the airship. I am very sorry if there were casualties. I have taken command of the mission and the ship. We have no place on this planet. We have not yet learned to live in harmony with ourselves, and everywhere are the idiot signs of our passing. I cannot allow you to bring news of this Eden back to those who would exploit it. I regret the necessity of abandoning you here. I comfort myself with the knowledge that you will be given a chance to learn to live in harmony with the natural forces here. The sacrifice is amply justified if the creatures of this planet are allowed to grow and develop without further interference. I wish you luck and godspeed.”

What follows is a race against time. With 48 hours before the repairs on the ship are completed, the crew must return to the Eleanor Moraes and regain control of it before Terry lifts off and strands the crew there. And as the game crosses certain thresholds, like the arrival on the ship, the clock shifts to real-time, where players might be down to the minute trying to keep Terry from achieving his escape.

And that’s just the first in a three-part adventure. The subsequent modules Face of the Enemy and War Machine reveal a plot by the Sathar, and go through a cavalcade of adventures, including making first contact with an alien species while examining a dangerous artifact and finally tying it all together with an adventure that draws on everything that players have learned in the War Machine:

As far as you know, no one has ever before captured an intact Sathar spaceship. You had one (until it blew itself up), and that makes you valuable property where the UPF is concerned.

Clues from that Sathar ship hint that the Sathar have a base in the FS 30 system, an unexplored star system just beyond the Frontier sector. The UPF want it checked out, and wants your group to do the checking.

The trouble starts as soon as you arrive; fighter patrols, ravaged planets, mysterious messages, and slave camps are the unmistakable calling cards of the Sathar. Their war machine must be stopped at any cost; does that cost include you?

These are fantastic adventures, and if you’re looking for a masterclass in playing with tension and varying stakes, we heartily recommend grabbing these adventures as part of the classic games reprints on DriveThruRPG.

So, with such a beloved game running on all cylinders in both the US and the UK–why was it killed just as it felt like the wave was beginning to crash?

The answer comes from one of the more controversial figures at TSR: Lorraine Williams. Originally brought on by Gygax, who found her while out in Hollywood as part of the TSR Entertainment ventures that led to the creation of the cartoon, a radio show pilot, and comic books, Lorraine Williams was brought on as a vice president who later became the president of TSR after a hostile takeover removed Gary Gygax from the company entirely.

One of the main functions of Williams was to save the company. By the time Gygax was oustered and 1986 dawned, TSR had gone from reporting a loss of $3.8 million dollars to reporting $2 million dollars in profits. And a lot of this can be attributed to Lorraine Williams’ early work at TSR. As the story goes, Williams never once played D&D, but helped lead the company through 2nd Edition:

When she first started at the company, she made a series of announcements which, while rather impolitic, at least had the virtue of being bold. Bill Slaviscek described Williams’ product strategy this way: “The company wasn’t afraid to try new things, and when something was working, they jumped on it and tried to make it bigger.” Under Williams’ reign, the company launched dozens of new products, starting with the 2nd Edition of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons.

The 2nd Edition of AD&D was touted as the most accessible version of the game that had ever been produced. Rules were cleaned up, and bizarre inconsistencies that had plagued the game since the days of Gygax and Arneson were finally resolved, much to the satisfaction of many players who found the new rule set easier to comprehend.

So why then, would she kill off one of their more popular games? To that we need only look to one of the game’s biggest inspirations: Buck Rogers. Williams, through her family, personally held the rights to Buck Rogers. And once Star Frontiers was closed down, TSR started manufacturing their own Buck Rogers RPG and board game. Though by then, interest in TSR and sci-fi had waned, and gamers had found their spaceship cravings satisfied elsewhere.

This was symptomatic of the problems that would ultimately bring down TSR. Too much growth and not in any kind of alignment with what its playerbase actually wanted. Still, we have Star Frontiers, and in it, many modern game elements explored ahead of their time.

Did you play Star Frontiers? What did you think?