Finding The Path – The Origins Of Pathfinder – Prime

How does one company go from publishing gaming magazines to one of the most popular fantasy RPGs out there? Here’s the story of Pathfinder.

Pathfinder is one of the most popular fantasy RPGs out there. And during the first half of the twenty-teens, it did what no other RPG has managed to do–topple D&D from the number one best-selling spot in RPGs. Though it wouldn’t last, the journey of Pathfinder to the top of the charts, from its humble origins as a “half-finished game” that was run as a desperation play when the company that founded it lost its ability to publish D&D material to an RPG franchise that’s popular enough in its own right, is a fascinating one. Today we’re going to take a look back at where it all began. Join us as we look back at the origins of Pathfinder.

D&D 3.0 – the Beginning

The story of Pathfinder is a story of three editions. Many people say it begins with Dungeons and Dragons 3.5. After all, it exemplifies the bedrock that would become Pathfinder. It was a system that wanted constant improvement, the fact that it was a .5 edition sets the tone for the birth of Pathfinder. But that’s only a part of the picture, the whole story of Pathfinder starts with 3rd Edition D&D and the acquisition of WotC by Hasbro, two years after WotC itself acquired TSR and all the associated D&D. In 2000, the now corporate-backed WotC had many changes on the horizon, including the launch of D&D 3rd Edition.

But with the launch of 3.0, came many layoffs. There’s a series of infamous Christmas layoffs in the year 2000, which were shocking to many because the launch of 3rd Edition had been such a smashing success, to the point that it launched its own genre of roleplaying games, which is important, but we’ll get to that later. For now, all you need to know is that 3rd Edition’s success didn’t prevent the “Christmas Layoffs” at WotC, which included the woman who would go on to become Paizo Publishing’s CEO, Lisa Stevens. Ironically, Stevens was Wizards’ first full-time employee, hired nearly a decade prior. She writes, in Designers & Dragons about her experience.

In return, all these companies were pushing more and more players towards the D&D Player’s Handbook and this aided in making the third edition launch one of the most successful ever. I enter this decade at the tail end of my Wizards of the Coast career. Fresh off the success of the 3rd edition launch, I was shocked when WotC cut me loose right before Christmas in 2000.

I missed a lot of the initial excitement of the d20 revolution and the spate of new companies arising to meet the demand for more d20 products. When I started Paizo Publishing in the summer of 2002, I was shocked to see the landscape of publishers changed so drastically. Green Ronin, Goodman Games, Monte Cook Games. Necromancer Games and a host of others were now some of the most successful RPG publishers around.

But employees aren’t the only things Hasbro is looking at removing at this point–as the next two years see a significant reduction in Wizards’ portfolio, trimming away some of its less successful programs to focus on publishing, as Hasbro put it, “quality toys and games.” Which meant, that by 2002, WotC was getting out of the magazine publishing business. And this is where Paizo Publishing first comes into being.

Enter Paizo

With WotC done with both Dungeon and Dragon, Stevens jumped on the opportunity. An employee at Wizards remembered that Stevens had expressed interest in both of the magazines, and formed Paizo Publishing along with Johnny Wilson and Vic Wertz. Debuting their first issues in 2002, beginning with a big introduction in Dragon #298:

Dragon #298 is the first issue released under the rubric of Paizo Publishing, LLC. The company’s name means, “I play!” in Greek.

You’ll still see the familiar faces in these pages because we brought the entire periodicals department of Wizards of the Coast onto our new publishing venture. We’re very excited about this because it means that those of us who produce the magazines now control our own destiny. Hasbro and Wizards of the Coast are very excited about this venture, as well. They love the way Dragon and Dungeon magazines have matured and they wanted to reward us for our good work.

Frankly, neither Hasbro nor Wizards of the Coast wants to be a magazine publisher. Both companies were built on publishing quality games and toys.

And with that, Paizo came into being. Dragon #299 launched Paizo onto the scene in full. And for a time, they were a magazine-only publisher. At first, Paizo started with three magazine: Dragon, Dungeon, and Star Wars Insider, which Wizards had taken over back in 2000. And with the magazines getting Paizo’s full attention during the midst of the d20 revolution, they were able to grow where other publishers who had been operating their own magazines had found them eventually more trouble than they’re worth. But Paizo had an interesting puzzle in the two different D&D magazines. Dragon continued to be the repository for all things D&D and community, but Dungeon is a different beast entirely.

With its focus on adventures, Dungeon was an outlier. After all it was aimed at people looking to run adventures, but it became a testing ground for some of Paizo’s more adventurous ideas. In fact, without Dungeon you probably wouldn’t get Pathfinder as we know it today.

Dungeon was known for its short adventures, and on occasion you’d get one or two that were connected, but when Paizo began its experiment with the “adventure path” — a concept introduced by WotC to define their interconnected campaign known as the Wrath of Ashardalon — everything changed. In Dungeon #97, gamers are introduced to the first of Paizo’s adventure paths, The Shackled City. This 12-part series of adventures took characters from 1st to 20th level, giving many people the chance to live out the D&D dream with most of the work done for them.

I can’t stress enough how much of a change this is. Paizo starts publishing campaigns that people can play through, and it helped shape the playstyle of tables throughout the era. Where many games would peter out around the mid-levels, these campaigns, which purposefully lead into the highest levels of play, gave players a glimpse into a whole other world, making it easy for DMs to run high level threats (which has always been one of D&D’s Achilles’ heels), since most of the work is already done.

The first gaming group I played with rapidly fell apart due to the burgeoning distance, but the second group I ever played D&D with was running through the Savage Tides, and it was a twice-weekly affair with players gradually growing in power and getting used to the complexity of high level play as we went along. So it was for many folks, who had a roadmap towards adventure. Not that there weren’t plenty of other pre-existing campaigns or linked adventures beforehand.

But Paizo’s refinements to the adventure path helped cement their success, proving popular enough that Paizo published hardcover compilations of their most popular adventure paths. Again, this is all while 3rd Edition is waxing gibbous. Alongside the Adventure Paths, Paizo starts putting out other accessories, including many that are tried-and-true staples of Paizo’s products today. Before Pathfinder even scratched the surface, there were Flip-mats and GameMastery products like Map Packs and Item Packs, and the Critical Hit Deck, which still sees use at tables today.

Rise of the Adventure Path

But in spite of these successes, the writing was on the wall, and by the time 2007 rolls around, Wizards of the Coast informed Paizo they would not be renewing Paizo’s license to publish the magazines, instead taking them back over and ending the print runs of them permanently. Fortunately, WotC gave Paizo a year to prepare, and this is where the massive pivot comes in. As Stevens writes in her retrospective on Paizo’s 10-year anniversary:

I have to give Wizards of the Coast a lot of praise for how they handled the end of the license. Contractually, they only needed to deliver notice of non-renewal by the end of December 2006; without the extra seven months’ notice they chose to give us, I’m not sure that Paizo could have survived. Wizards also granted our request to extend the license through August 2007 so that we could finish up the Savage Tide adventure path. This gave us quite a bit of time to figure out how we were going to cope with the end of the magazines. It would have been very easy for WotC to have handled this in a way which would have effectively left Paizo for dead—all they would have had to do was follow the letter of the contract. Instead, they treated us like the valued partner we had been, giving us the ability to both plan and execute a strategy for survival. For that, I will always be thankful.

And survive they would. Though Paizo had to pivot, and sharply. Over the course of 2006, they revamp their strategy and announce in 2007 their intent to publish the Pathfinder Adventure Path, due to debut at that year’s Gen Con. And this is the Paizo Adventure Path in all its glory. Six-book sets, the world of Golarion, all the trimmings. The only thing missing was the game itself. But that would come later–for now, Paizo knew that its survival was entirely dependent on the Adventure Path.

The news caused us to kick our plans for other product lines into a higher gear. In fact, before even two hours had elapsed, we’d already scheduled an offsite meeting at my house. We knew that the key to our survival beyond Dragon and Dungeon hinged upon our mastery of creating adventures, particularly Adventure Paths. So we started to plan for what would end up being one of the most shocking announcements in the history or RPG gaming… but that tale will have to wait until the 2007 blog!

And as Pathfinder Publisher Erik Mona puts it:

In the days and weeks to come, a lot of those answers grew more and more clear. Paizo would go on. Once we came up with the idea behind a “monthly Adventure Path book” (not yet called Pathfinder), the management team resolved to chart a path to the company’s survival that kept every employee intact. We’d already experienced a bunch of layoffs, and to transition the company into its new form in 2007, we’d need all hands on deck. To their credit, Wizards of the Coast graciously extended our license by a few months so we could bring the Savage Tide Adventure Path to its proper conclusion, and even though it’s fair to say things between the two companies were very awkward for a while, everyone still remained friendly and cordial.

That’s the stage as it’s set for Paizo when the big year rolled around. 2007 meant preparing for the final issues of Dragon and Dungeon, as well as launching their first Adventure Path, which took the form of a 96-page book (well six books all in all), while laying out the groundwork for their own in-house developed world of Golarion, which had previously been explored in GameMastery supplements.

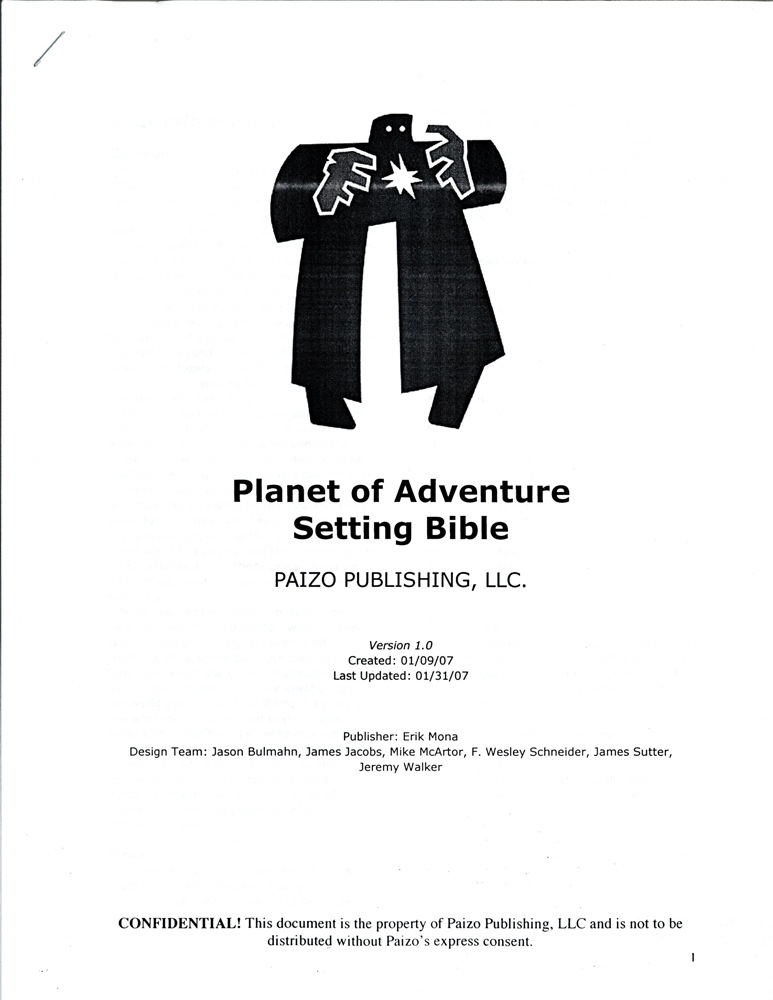

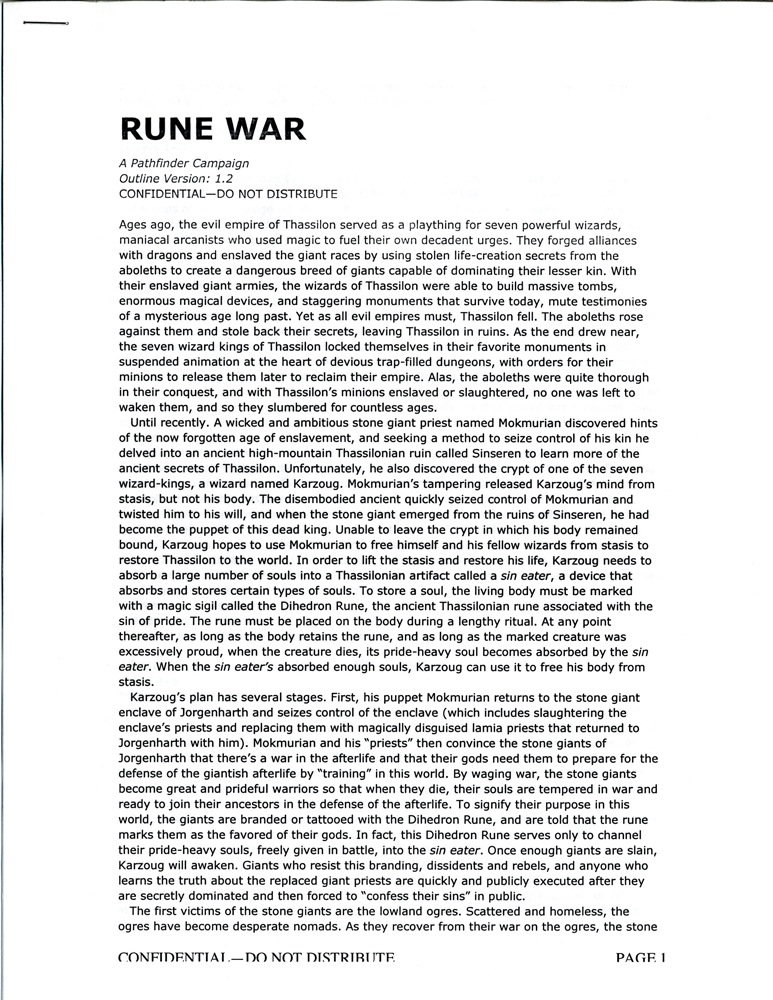

Here’s a look at some of the outline documents, as shared on Paizo’s own blog. In it we can see a look at the well-established history of Golarion now. Here’s the early days of the Rune War, and the outline for the adventure that would launch Pathfinder. As all this is happening, Paizo is working hard to finish off the Savage Tide adventure path, which culminates in a showdown with Demogorgon, and is generally warmly regarded as one of the best 3.5 Adventure Paths out there.

And here, we need to pivot ourselves. In the midst of Paizo’s restructuring, planning new Adventure Paths and new accessories and two new lines of 3,5 compatible products, there came the shadow of the giant: D&D was preparing to announce a 4th Edition. This would prove to be a massive challenge for roleplaying as a whole. And to understand that, we need to talk about the importance of 3rd Edition, 3.5 Edition, and the OGL that helped launch a thousand games.

About the OGL

With 3rd Edition came the d20 Trademark License and Open Gaming License, which opened the doors for anyone to publish D&D and D&D accessories using the d20 brand, effectively turning the d20 system into an RPG engine that other people could use to power their games, much like Epic Games did with their Unreal Engine just a few years earlier. And much like the Unreal Engine enabled more games to be created, the d20 System saw the creation of a new kind of company–one dedicated to publishing d20 content.

Three companies hit the ground running with their own D&D adventures ready to go on 3E Launch Day: Green Ronin with Death in Freeport, Atlas Games with Three Days to Kill and Necromancer Games with The Wizard’s Amulet. But these were hardly the only ones out there. The first few years of the aughts were a veritable d20 boom. Companies could make or break themselves on how quickly they could adapt to the change to the market. Green Ronin, for instance, started as just another RPG publisher, but quickly adapted to the d20 market and earned a spot at the top. How was all this possible? Well, let’s take a look at the Open Gaming License itself.

Put forth in 2000 by Ryan Dancey, one of the folks that spearheaded the acquisition of TSR by Wizards of the Coast, the Open Gaming License is a short document that outlines how you can use the “Open Gaming Content.” Here’s a snippet:

1. Definitions: (a)”Contributors” means the copyright and/or trademark owners who have contributed Open Game Content; (b)”Derivative Material” means copyrighted material including derivative works and translations (including into other computer languages), potation, modification, correction, addition, extension, upgrade, improvement, compilation, abridgment or other form in which an existing work may be recast, transformed or adapted; (c) “Distribute” means to reproduce, license, rent, lease, sell, broadcast, publicly display, transmit or otherwise distribute; (d)”Open Game Content” means the game mechanic and includes the methods, procedures, processes and routines to the extent such content does not embody the Product Identity and is an enhancement over the prior art and any additional content clearly identified as Open Game Content by the Contributor, and means any work covered by this License, including translations and derivative works under copyright law, but specifically excludes Product Identity. (e) “Product Identity” means product and product line names, logos and identifying marks including trade dress; artifacts; creatures characters; stories, storylines, plots, thematic elements, dialogue, incidents, language, artwork, symbols, designs, depictions, likenesses, formats, poses, concepts, themes and graphic, photographic and other visual or audio representations; names and descriptions of characters, spells, enchantments, personalities, teams, personas, likenesses and special abilities; places, locations, environments, creatures, equipment, magical or supernatural abilities or effects, logos, symbols, or graphic designs; and any other trademark or registered trademark clearly identified as Product identity by the owner of the Product Identity, and which specifically excludes the Open Game Content; (f) “Trademark” means the logos, names, mark, sign, motto, designs that are used by a Contributor to identify itself or its products or the associated products contributed to the Open Game License by the Contributor (g) “Use”, “Used” or “Using” means to use, Distribute, copy, edit, format, modify, translate and otherwise create Derivative Material of Open Game Content. (h) “You” or “Your” means the licensee in terms of this agreement.

2. The License: This License applies to any Open Game Content that contains a notice indicating that the Open Game Content may only be Used under and in terms of this License. You must affix such a notice to any Open Game Content that you Use. No terms may be added to or subtracted from this License except as described by the License itself. No other terms or conditions may be applied to any Open Game Content distributed using this License.

The most relevant part is that the OGL splits D&D into two distinct parts: “open gaming content” which is free to use–and it’s worth pointing out things like rules and mechanics aren’t copyrightable in the first place, and things like formatting or stat blocks are in dispute even to this day–and “Product Identity” which are things like Mind Flayers and named characters and the Forgotten Realms.

Pathfinder is Born

This is why Paizo was able to keep using the same system–but a new Edition could be troubling. Even the switch from 3.0 to 3.5 was enough to gut some companies who weren’t fast enough to adapt to the new system. And with 4th Edition announced and due to debut in 2008, Paizo had its work cut out. In early 2008, they had some crucial decisions to make, should they follow through with their plans or should they try and adapt to 4th Edition’s new mechanics? The fate of the company seemed to ride on that decision, as Lisa Stevens writes:

We dutifully sent Jason Bulmahn to Wizards’ D&D Experience in Fort Wayne, Indiana that February. Jason’s mission was to learn as much as he could about 4th Edition, play it as much as he could, and report back with his findings. From that, we would ultimately make a decision that could make or break us. The tension was agonizing. I could barely sleep at night as my mind wrestled with the options. If we made the wrong decision, it could very well mean the end of Paizo.

When Jason returned from D&D Experience, he laid out all the information that he had gleaned. From the moment that 4th Edition had been announced, we had trepidations about many of the changes we were hearing about. Jason’s report confirmed our fears—4th Edition didn’t look like the system we wanted to make products for. Whether a license for 4E was forthcoming or not, we were going to create our own game system based on the 3.5 SRD: The Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. And we were already WAY behind schedule.

Jason Bulmahn had a plan to develop a game based on an evolution of the 3.5 ruleset, keeping to the Open Gaming License set out before. And with 2008 dawning, work began on Pathfinder, until in March, Paizo’s website came down, replaced with a picture of Goblins “forcing a decision” on Paizo HQ.

Then the website went live with the announcement and the launch of the Alpha Playtest. From there, the rest is history. 2008 is a rapid-fire year that sees the Beta developed and ready to launch in 2008, meanwhile Monte Cook joins the Design team and the 3.5 Edition quickly becomes 3.75, or Pathfinder.

And in 2009 the game launches properly, while 4th Edition is also breaking away to do its own thing. Both of these games would drive the RPG industry in two different directions. For a while Pathfinder takes the lead, and 4th Edition creates a great deal of trouble for WotC as emerging digital tools take hold. But the evolution of both Pathfinder and 4th Edition is a whole other story in its own right. For now, this is where Pathfinder begins, goblins running amok, one company betting everything they have on a game that they love, and the clatter of d20s.

Happy Adventuring