D&D: Mythic Odysseys Of Theros Has The Secret To Adventure

They weren’t joking around with the title. If you want to send your players on Mythic Odysseys, the new D&D books has the rules you’ll want.

We’ve talked before about how great the new Theros book is. It adds a lot of spice to the original D&D flavor that makes for a high-powered kick in the pants. Theros is a high-powered plane where champions go to war with servants of the gods, while the divinities interfere in mortal events to their hearts content. There’s a lot to live up to, but the Mythic Odysses of Theros has rules to create adventures that feel a little different than most. Today we’re going to take a look at how Theros’ new rules uniquely prepare you to run some Odysseys of your own.

Exploration is the most overlooked of D&D’s “three pillars” — the other two being combat and social interaction. It’s not hard to see why, “exploration” is such a nebulous concept, and the rules don’t necessarily help out a player/DM who doesn’t have a sense for what makes that fun. Until Theros came along with some helpful advice for everyone. There are two main sets of exploration rules to play with, inspired by some classic myths: nautical adventures, and journeys into the Underworld.

Nautical Adventures could easily be written off as “travelling but the DM gets to use sea monsters and it sucks if you fall off the boat,” but Theros has more to it than that. It wants to capture the feel of bold sailors recounting mythic adventures, and it does it by turning to the stars. Seriously, the best advice it gives for sailing adventures is to get a little more Star Trek:

Knowing the difference between port (left) and starboard (right), or a ship’s bow (front) and stern (rear) isn’t necessarily important to legendary heroes, particularly when brave crews sail along with them. Feel free to think of the ship your heroes travel upon less in the terms of a pirate story (full of commonplace duties and dangers) and more like a vessel in a space-faring, sci-fi adventure (where mundane operations often fade into the background). How much a story engages with course setting, provisioning, periods of inactivity, and other aspects of long ocean journeys is ultimately up to you and the players to decide, but consider cleaving to what the group thinks is fun rather than stretching for unnecessary accuracy (whatever that might mean for a world as magical as Theros).

And the best way to do that is to break it down into a few easy steps. First things first, as a DM you’ll want to give your party a reason to head out at sea, and it wants you to know that setting out is only part of the journey. Getting lost and trying to find your way back is just as exciting as trying to slay a monster.

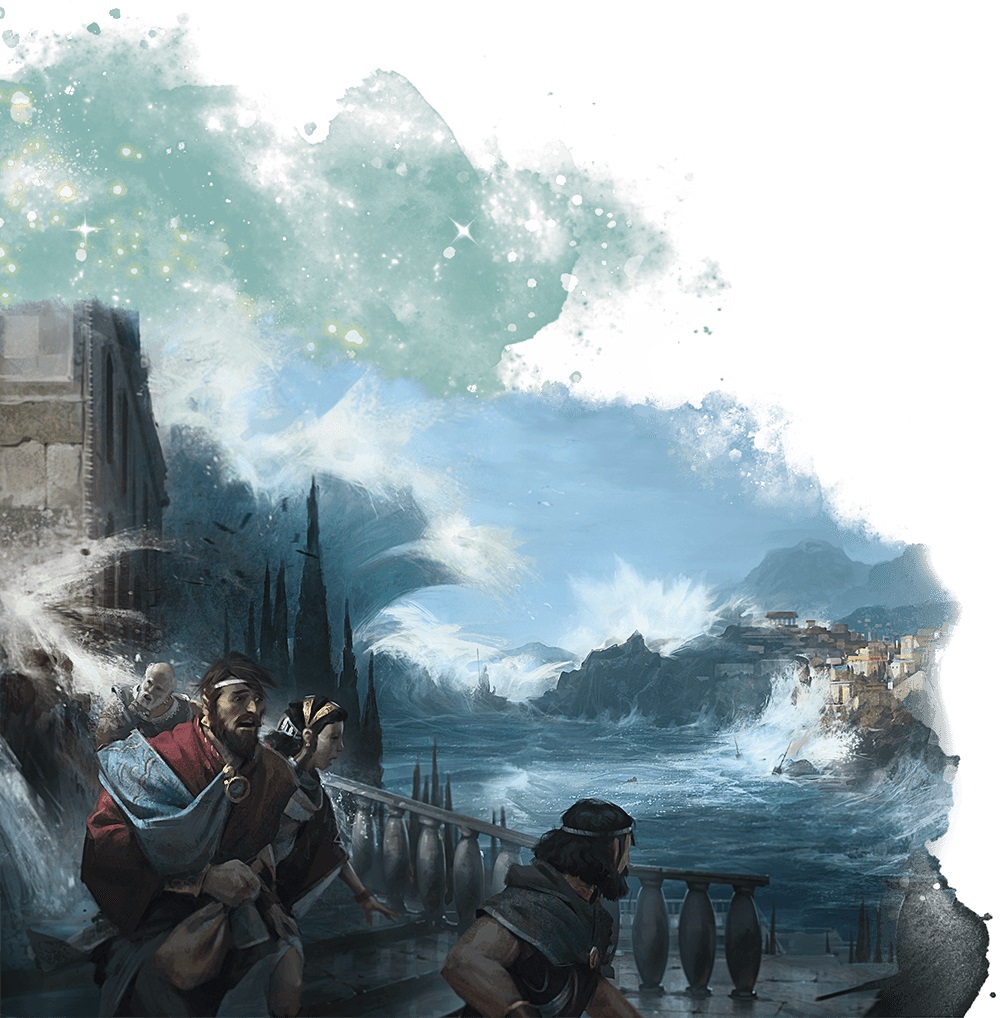

But how do you structure these kinds of adventures? Again, turn to sci-fi. The seas of Theros are dotted by “mystical islands” and it’s helpful to think of these as separate planets that one might visit if this were a Star Trek. Each island can be its own episode as you explore strange shores and navigate treacherous illusions, or discover that you’re walking atop a gigantic slumbering creature.

Or deal with the inhabitants of it–be they undiscovered civilizations, creatures who believe they’re the last of their kind, warring city-states, or stranger still. And if you want to go deeper still, Theros has some great guidelines for traversing the ocean depths, giving higher level parties (or those who can breathe water naturally) some great seeds for heroic adventure.

The other big adventure they touch on is a journey into the Underworld. Like Orpheus, who ventured after Eurydice, you want to have a reason to venture into the Underworld, whether or not you go willingly. If you venture willingly into the Underworld, you’re in for encounters with demons and mythic beasts and worse, and getting out is harder than getting in. The book lists a few different ways to escape, but the real excitement is in how the game hanges the way you look at character death:

When a character dies, their adventures don’t need to end. The Underworld presents an opportunity to provide a sense of closure for deceased characters—as adventurers’ ends tend to be quite sudden—or to give them a way to continue engaging in the quest while their companions attempt to bring them back to life.

AdvertisementThese interludes can be played as brief scenes where the player of the dead character is in the spotlight and the rest of the group observes. Alternatively, the rest of the group could participate as NPCs or even monsters the dead character meets and interacts with.

Options include narrating an Epilogue where your hero sees the souls of people they’ve lost along the way, or perhaps you get a glimpse of your hero’s soul waiting to be resurrected, taking a moment to reflect on what they have done, and what might happen if nothing changes.

These are just a few examples, but this already has me excited to play with these kinds of stories. It takes some of the sting out of dying (and dying in Theros isn’t any easier, so you might feel less bad about deliberately attacking downed foes, otherwise you might never get to this part), and opens up new avenues of adventure.

Happy Adventuring!