PRIME: The RPGs That Went To Hollywood

There are plenty of TV shows that have their own RPG now, from Altered Carbon to the Buffyverse. But that door swings both ways. See which tv shows began as RPGs.

Roleplaying Games and television have a storied history. RPGs and the movies also have a storied history, but it’s less of a tale of cool ideas taking new form, and more a tale of irony, fumbled attempts, and Jeremy Irons squeezing every last ounce of blood from the set he’s chewing on.

We’ve talked before about why a D&D movie is a tricky thing to accomplish, notably that it requires a mix of humor and an understanding about what the rules are, what the game is, and why people love it so much. Otherwise you just end up with a generic fantasy story wrapped up in some D&D trappings, but touching on nothing that really makes it feel like D&D.

Or, as Gygax did in his original concept for the script, you cling too tightly to some idea of whatever you think D&D is supposed to be and you end up with something like the original draft of the never-produced D&D movie:

This is your dungeon,” the Nightking explains, “You are in it. There are no guards. The doors are open… which door did you come through? Can you remember? Was this the door?” In his villainy, he continues, “You are surrounded by my Underworld. The choice is yours.” They can remain in the seven-sided room until the Master fades, or explore the castle, “for I have things outside in store for you.” He then unceremoniously departs.

While the party deliberates over which door to take, the Nightking raises the temperature of the floor in the seven-sided room until they are forced to choose. Drobni carries the Child as they make their way through a surreal snowy landscape that soon turns into a dungeon passage. “It’s a maze,” Margot concludes, “We’re in a maze.” The Nightking briefly interrupts to inform the party that “something is hunting for you.” As they begin making their way from chamber to chamber, it soon becomes clear that a dragon pursues them.

A dragon in a dungeon. (emphasis ours)

AdvertisementThe party is briefly separated, and Odo, Drobni, Margot, and the Child come face-to-face with the dragon. To save the Child, Odo throws himself into the dragon’s jaws. But then Drobni, who cries “Not my Odo!” growls in rage and grabs the dragon’s tail. Thumbless Drobni starts to “pivot,” which throws the dragon off balance, and then “pivot harder, harder, turning in a circle,” until the dragon is lifted off the ground, “not far-but just enough to swing it like a bolo, in a circle.” Finally, Drobni releases the tail, and the dragon is flung into a stone wall. “We hear its skull crack as it crashes on the stone,” and the dragon is slain.

But it’s not all bad. There’s something about the nature of an RPG story that translates incredibly well to television. Maybe it’s the way that each episode is like an adventure all its own, maybe it’s the way you can string each season together like a campaign, but whatever the case, for all the problems that crop up when trying to create a movie, they seem to just create fertile ground for TV shows based on RPGs. And not just loosely inspire by, but adapted from. Some of your favorite shows (and many of your not-so-favorite) began as RPGs. The Expanse, famously, was based on a play-by-post game that took place in a lavishly detailed setting.

But the Expanse isn’t the only TV series to have its roots with an RPG, so let’s step back through the ages and look at some of the many games that made the jump to the small screen.

Dungeons & Dragons

This one’s a gimme, given that it’s the name of the game right in the TV show but it bears mentioning because the story of how Gary Gygax went from being president of D&D to being “banished to the West” in all but name, where he found immense success and got a three-season animated special that helped propel D&D into the mainstream, complete with tie-in action figures and everything. It all starts in the 1980s, when TSR is experiencing dizzying highs and crushing lows year by year.

Back in 1975, when TSR Hobbies, Inc. was formed, and Gygax was reduced to a minority stockholder. Well, as TSR grows, Brian Blume’s brother, Kevin Blume, rose through the ranks, eventually buying out his father’s shares and leaving TSR with three presidents, which ends about where you’d expect.

“The fact is, though, that there were three persons on the Board of Directors of the company – Brian Blume, Kevin Blume and me. Similarly, while I was the President and CEO, Brian placed himself in charge of creative affairs, as President of that activity, while Kevin was President of all other operations. This effectively boxed me off into a powerless role. If a ‘President’ under me did something I didn’t like, my only recourse would be to take the matter to the Board of Directors where I would be outvoted two to one.”

“I have spoken earlier of the structure that the Blumes imposed on TSR in 1981. As another example of things before then, late 1979 or early 1980, I issued some instructions. When Brian heard what I had ordered he shouted loudly for all to hear: «I don’t care what Gary said. I own controlling interest in this company and it will be done the way I say!». I should have parted ways with TSR then and there, but I still had a lot of loyalty to the company and the vision upon which it had been created. Anyway, from that point on, I had little control, and in general what I desired be done was ignored or the exact opposite was put in place.”

Subscribe to our newsletter!Get Tabletop, RPG & Pop Culture news delivered directly to your inbox.By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

In 1983, TSR reorganized and split into four separate companies: TSR, Inc. (the main one we still think of as TSR), TSR International, TSR Ventures, and TSR Entertainment, Inc:

On June 24 [1983], TSR released in excess of 40 Employees — including vice president Duke Seifried — and reorganized into four companies. Each company bears the same board of directors (E. Gary Gygax, Kevin Blume, and Brian Blume). TSR, Inc. will manufacture the role-playing game line and other products, and is further divdied into six departments: Games/Toy, Publishing/Crafts, Finance, Manufacturing, Marketing and Human Resources. TSR Entertainment Corporation (name not final) is the TSR liaison with motion pictures and television. TSR Ventures is a research and licensing company. TSR Worldwide Ltd. is the international-sales and development branch.

Depending on which story you believe, he either exiled himself or the Blumes exiled him to Hollywood, as a part of TSR Entertainment’s founding. And this section is such an interesting branch–it reflects a goal that modern-day WotC is still exploring: media dominance. At the time, TSR Entertainment existed to pitch D&D shows, be they television or movies.

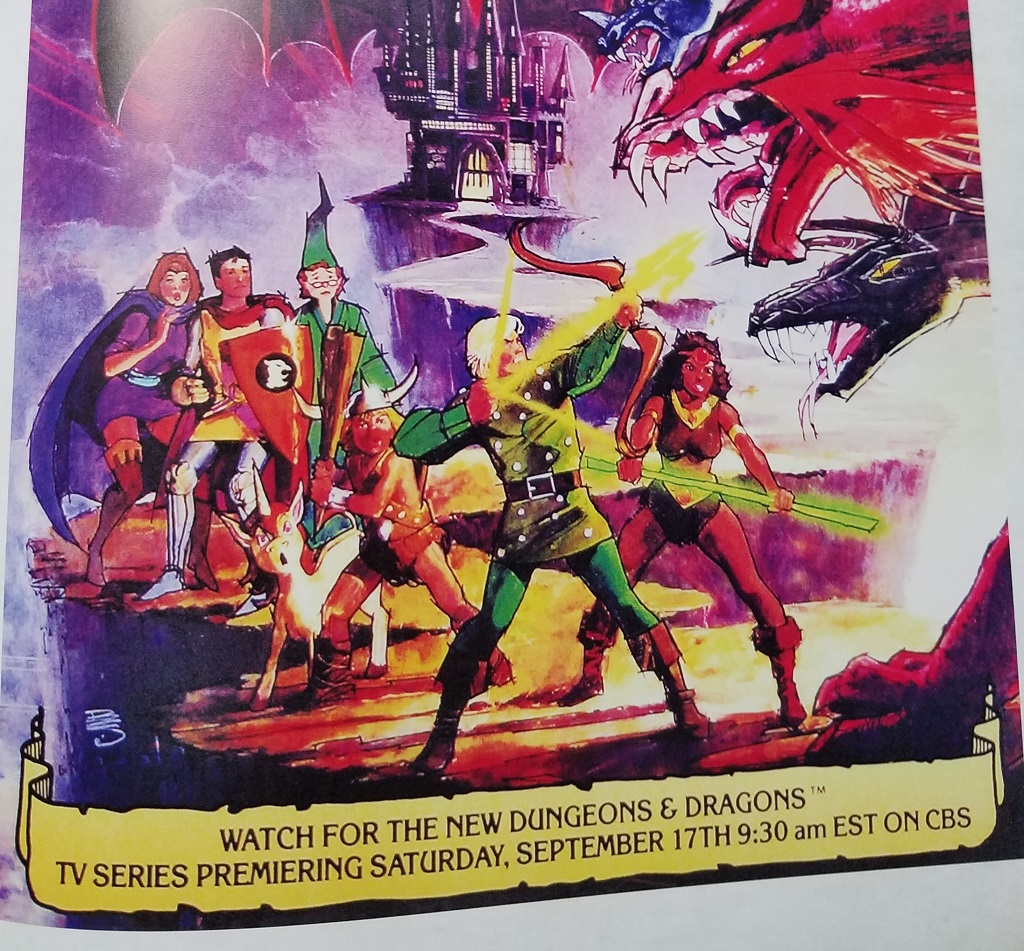

And to a degree, Gygax succeeded, securing a deal with Marvel Comics to create the Dungeons & Dragons cartoon, which premiered in September of 1983 and ran for three seasons:

In other TSR news, a Dungeons and Dragons Saturday Morning Show cartoon series, which has been arranged through the Marvel Comics film division will premier on CBS on September 17. TSR’s negotiations for a possible Marvel superhero role-playing game are not yet complete.

It’s an interesting time, because the cartoon started coming up in the wake of the satanic panic. But look at the fertile ground that the show was planted in. In the 80s, we had the first blossoming of fantasy, with movies like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Conan films, and wildly successful toy-selling cartoons like He-Man and the Masters of the Universe making millions for the right folks.

The question is, who were the right folks? Gygax managed to negotiate a deal with Marvel to develop a D&D animated series which would be sold to CBS. Marvel productions found a difficult partner with Gygax though, who seemed interested in living up the “glamorous Hollywood lifestyle” on the company dime. As they mention in Of Dice and Men, Gygax famously ran up a $10,000/month expense.

Gygax did not live the life of an exile in Los Angeles. TSR was flush with cash, so he rented a mansion on Summitridge Drive in Beverly Hills and played the part of Hollywood hotshot, dining with movie stars, partying with beauty queens, getting driven around in fancy cars. Before long, his expenses approached $10,000 a month — more than $20,000 in 2012 dollars. According to some accounts, he paid half a million dollars to The Lion in Winter screenwriter James Goldman to write a script for a D&D movie.

But that’s tame in comparison to the details spilled in The Believer, which paints a more detailed picture of Gygax’ Hollywood antics.

Gygax rented King Vidor’s mansion, high up in Beverly Hills, with a bar, a pool table, and a hot tub with a view of everything from Hollywood to Catalina. He had a Cadillac and a driver; he had lunch with Orson Welles, though he mentions with Gygaxian modesty that “I find no greatness through association.”

Here a whiff of scandal enters the story. Gygax had separated from his first wife, the mother of five of his six children; he had not yet married his second wife, Gail. In the interim, well, it was Hollywood, and Gygax was in possession of a desirable hot tub. Gygax refers to the girlfriends who used to drive him around—he doesn’t drive; never has—and to a certain party attended by the contestants of the Miss Beverly Hills International Beauty Pageant. But he also mentions that he had a sand table set up in the barn, where he and the screenwriters for the D&D cartoon used to play Chainmail miniatures.

This is perhaps why Gygax, unlike other men who leave their wives and run off to L.A., is not odious: his love of winning is tempered by an even greater love of playing, and of getting others to play along. He ends the story about the beauty pageant girls with the observation that Luke, who was living with him at the time, was in heaven, seated between Miss Germany and Miss Finland.

As you can expect, Gygax was a bit hands-off on this deal, leaving the team at Marvel Studios to find a network to sell the show too, which they did, in CBS. As show developer Mark Evanier puts it:

[Writer-producer] Dennis marks had done a very fine job on the show but, as sometimes happens when something’s around long enough, everyone involved had grown somewhat punchy. In the development process, as the format is being worked out and characters are added, deleted or defined, you often get lost in the ninety-third revision. The CBS folks felt that Dungeons & Dragons was “almost there” as a series but that it needed some work from a fresh mind. I have an extremely fresh mind to go with my fresh mouth.

Talks were held, suggestions made, contracts negotiated and I wound up doing the pilot and format for Dungeons & Dragons — both in about forty-eight hours, which was about all I had before CBS had to set its schedule.

And with that the show kicks into high gear. Though even then, the show is still facing a rocky road to success. Evanier talks about the pressure parents groups were putting on the writers of the show:

Dungeons & Dragons was a series about six kids who were transported to a dimension filled with wizards and fire-snorting reptiles and cryptic clues and an extremely-evil despot named Venger. The youngsters were trapped in this game-like environment but, fortunately, they were armed with magical skills and weaponry, the better to foil Venger’s insidious plans each week.

The kids were all heroic — all but a semi-heroic member of their troupe named Eric. Eric was a whiner, a complainer, a guy who didn’t like to go along with whatever the others wanted to do. Usually, he would grudgingly agree to participate, and it would always turn out well, and Eric would be glad he joined in. He was the one thing I really didn’t like about the show.

So why, you may wonder, did I leave him in there? Answer: I had to.

That’s right, Eric the Cavalier, everyone’s least favorite killjoy who never wanted to do anything fun was there to teach a moral lesson to kids of the 80s: “The group is always right…the complainer is always wrong.” I wonder how that worked out for them.

At any rate, Dungeons & Dragons ran for three seasons with a total of 27 episodes, 28 if you count the apocryphal “final episode” which only exists on the internet.

The Expanse

But let’s leave the D&D cartoon in the past, where it belongs (outside of the occasional Brazilian car commercial), and look at another show that made the jump from RPG to the small screen, The Expanse.

The Expanse is the brainchild of George R.R. Martin collaborators Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck, working under the name James S.A. Corey–which makes me wonder if every author with two initials is secretly two people, because who even knows what’s real anymore. But, leaving all that aside, readers might be familiar with the Expanse as theSyFy-and-later-Amazon Prime series which will at some point have at least five seasons, or possibly as the ongoing nine-book series that starts with Leviathan Wakes.

This epic space opera which grinds into harder science fiction than most sci-fi shows, has a robust world full of characters that feel like they’ve always existed in it. But that is not where the story begins. Before it was even a book, the Expanse began as a roleplaying game.

In fact, it almost began as an MMORPG, when developer Franck joined forces with a friend hoping to develop an MMO for a Chinese ISP as an incentive to get people to sign up for its service. This is back in the frontier rush of MMOs when games like EverQuest and EVE Online hadn’t quite been edged out by new kid on the block, World of Warcraft yet. As Franck puts it:

At the time, EVE was out as an SF setting; it’s a cool game, but it’s limited to just the spaceships. I really wanted a version of EVE, or something like EVE, where you could actually get off of your ship and have adventures on the ground. That was sort of the initial idea, and then I took this near-future setting and built it out to accommodate spaceship and ground-based adventure.

We wanted to do different things from World of Warcraft. Of course, they have two factions, the Alliance and the Horde, so we had three factions: Earth, Mars, and the OPA. Those would have been the factions you started out your character in.

Although you can imagine what developing an MMO was like in those days, many didn’t even get off the ground, and once the ISP realized how much it would cost to develop the MMO being pitched, they backed off and the Expanse’s world lay dormant for a time. Until 2006, when Franck started running a roleplaying game on a play-by-post gaming forum, where characters (who would go on to influence events in the book) emerged in the tri-factioned world he’d started building out.

I had all this material, and I’ve been a gamer all my life — computer games and role-playing games — so I started play testing in the universe with my gaming buddies. Did it work? Were there interesting stories to tell? What kinds of characters would be fun to play in that setting? Not with any real purpose in mind — just because that’s something I do for fun. So I started running games in the setting. I came up with a rule system that worked for a pen-and-paper setting and started gaming in it.

I met Daniel years later when I moved to New Mexico and we were in the same writing group together. He and his wife came over to do some gaming with my wife and I. That was years after I started running games in this setting. Actually, Daniel was late to the game — the first game I ran in this setting in New Mexico was with a completely different group. That gaming group was Melinda Snodgrass and Ian Tregillis and George R.R. Martin and my wife.

As you can see, the game brought the two partners together, as Franck and Abraham started playing a game out in Albuquerque:

I started running a game there. That’s when he saw the binder, and he said, “Have you ever considered writing novels in this setting?” and, of course, I hadn’t, because I’m really lazy. So, he said, “Hey, you know what you should do? You should let me write a novel in this setting, and we can split the money,” which is like the opposite version of the gag that every writer hates when people walk up to them at a convention and say, “Hey, I’ve got a great idea: You write it, we can split the money.” So, I actually had an award-winning and respected novelist coming to me and saying, “You’ve got a great idea, I’ll write it, and we can split the money.” He always tells me that I’m not allowed to tell that story, but I tell it anyway. He wrote the first chapter, and again, it was like the thing with my sister writing her story idea: He did it wrong. So, I said, “No, this is wrong. I’m going to rewrite it.” I rewrote it the way I wanted it, and he said, “Yeah, no, this is actually great. You should just write half the book.” So that’s how we started: I wrote half and he wrote half, and that’s what we’ve done ever since.

And once the books become popular enough, SyFy picked them up, hoping to find a show that would scratch the Battlestar Galactica itch that had driven much of that network’s success. From there, a much wider audience gets introduced to the world where the Rocinante and her crew help guide so much change.

But, as the pair point out, even adapting the world over from the game was a challenge. “Games are terrible books” the pair point out, offering this advice to writers:

Don’t take your D&D campaign and write it down as a book. It doesn’t work. Maybe you can take the setting, maybe you can take some of the characters, maybe you can take some of the plot points, but you have to completely redesign the order of events because in gaming, of course, so much of it is interactive, and so much of it is you, as the game runner, reacting to what your players have done and changing the setting or the story to accommodate the actions they’ve taken. In a novel, which is much more driven by the narrative, you actually have to have a much tighter grip on where the story is going, much more control over how you release information to the reader. If you actually read the game I had run and then read the story, you would recognize similarities, but the major plot is very different and how I feed information to the reader is very different than how I feed information to players.

And there you have it folks. Games might not be the best way to start a movie, but they can be fertile ground for TV shows. Who knows what TV shows might creep out of today’s games, already aimed at emulating genre. What would an Apocalypse World or Blades in the Dark game look like? We may one day find out.

Until then, happy adventuring!