D&D: Alignment Does Almost Nothing

Alignment in D&D is one of the most contentious things about 5th Edition, and it doesn’t really do anything in the game. Here’s how it works, and doesn’t.

If you’ve been paying attention to some of the big conversations that have been going on in the D&D community, you’d know that alignment is one of the main issues of the ongoing discussion and the push to make D&D more diverse and inclusive to folks of all stripes. For a while now, folks have been calling out the fact that Orcs always being evil reflects harmful stereotypes, WotC themselves acknowledge it in their diversity statement:

And a lot of folks have an opinion about how heady concepts like “good” and “evil” fit into the game.

But today we’re not here to talk about what alignment means, but rather, what it does. Which is to say, nothing. That’s right, alignment doesn’t do anything in D&D 5th Edition. It almost feels like the designers wanted to get rid of it, but have been too afraid to leave behind one of the “iconic” parts of D&D, just like ability scores in lieu of ability score modifiers. We only care about ability modifiers, we only ever use ability scores when increasing them to find out if the modifier changes. And just like there’s no functional difference between a 14 and a 15 (for the most part) being evil, good, or neutral has very little bearing on your character, mechanically. Let’s take a look.

In the Player’s Handbook alignment is barely mentioned. You get told to pick out an alignment for your character, you’re presented with the same nine options that you’ve seen in countless memes:

You find it mentioned in a few other places–the character traits that you use to inform your personality under Backgrounds, starting on page 127, have an alignment descriptor tag. For instance the acolyte might take an ideal like Faith, which reads “I trust that my deity will guide my actions. I have faith that if I work hard, things will go well,” and it’s tagged “(Lawful)”. But that just means that the ideal is one that tends towards lawfulness, but you could play a chaotic or neutral character and still hold that ideal.

But in the places where you’d expect that it would show up–places like Clerics or Paladins, whose story might be shaped by their alignment, it doesn’t. Unlike, say, 3.5 edition where your alignment had to match your deities at least a little, you could play a Lawful Evil Cleric of Pelor, for instance. Or a Neutral Good follower of an evil deity–and that owes largely to the fact that deities kind of take a backseat in 5th Edition, they largely appear as a collection of traits and powers that Clerics get until you use them in the game.

And Paladins aren’t required to be Lawful Good anymore, they haven’t since 4th, or 3.5 depending on what sourcebooks you used. But even their abilities don’t key off of whether someone is good or evil. Divine Sense, which used to be Detect Evil, references evil and good, sort of, but not really:

The presence of strong evil registers on your senses like a noxious odor, and powerful good rings like heavenly music in your ears. As an action, you can open your awareness to detect such forces. Until the end of your next turn, you know the location of any celestial, fiend, or undead within 60 feet of you that is not behind total cover. You know the type (celestial, fiend, or undead) of any being whose presence you sense, but not its identity (the vampire Count Strahd von Zarovich, for instance). Within the same radius, you also detect the presence of any place or object that has been consecrated or desecrated, as with the hallow spell.

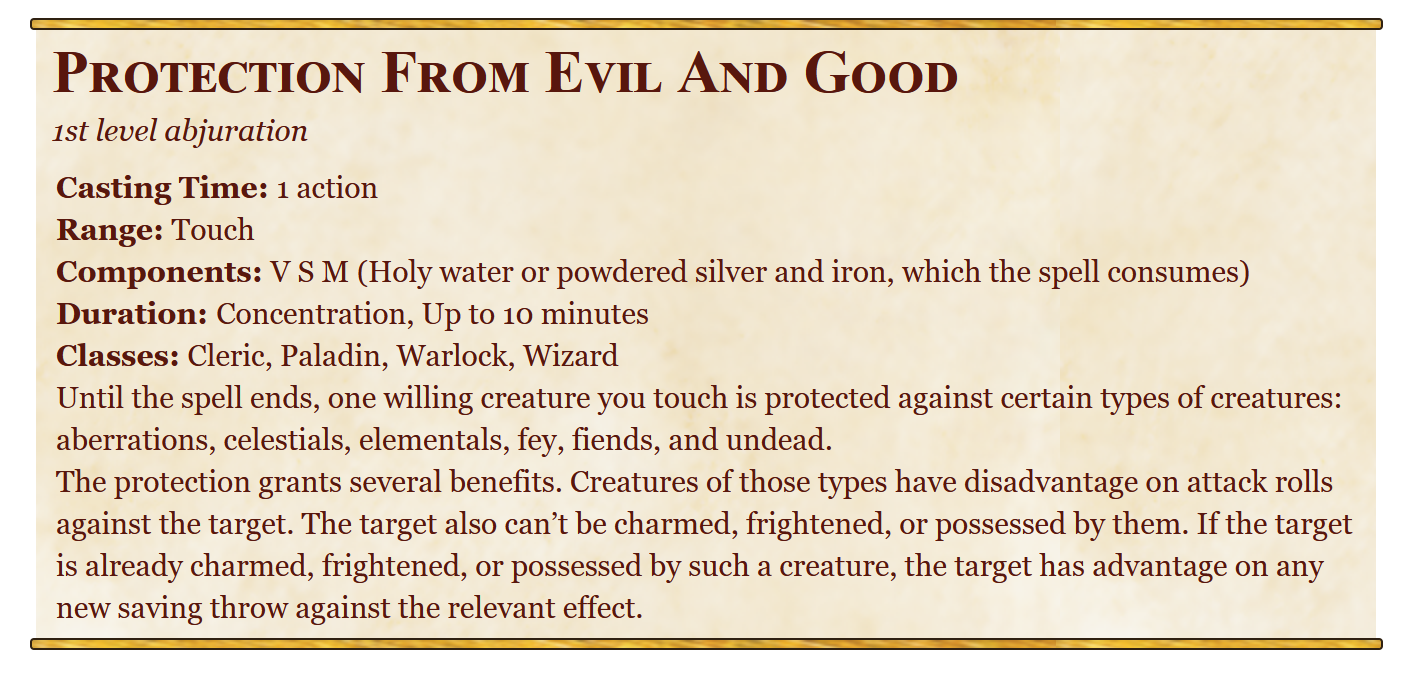

To sum up, all it does is reveal if a celestial, fiend, or undead creature is within 60 feet of you. Which is basically how the spells that reference good and evil work. Both Detect Evil and Good and Protection from Evil and Good only work on creatrues if they are classified as either “aberration, celestial, elemental, fey, fiend, or undead.” Detect lets you know where the creature is, and Protect gives you defensive bonuses and prevents you from being charmed, frightened, or possessed by those creatures.

For the most part though, good and evil are largely academic. They are concepts in D&D but they don’t touch the rules nearly as much as they did in previous editions. It feels like the designers have been distancing themselves from the concept for the last few iterations of D&D. In 4th Edition you just had Lawful Good, Good, Evil, Chaotic Evil, and Unaligned. And in 5th Edition the classic alignments are back, but they’re just descriptors that influence the story.

Which is fine, but that’s not how they’re presented in the book. You’re told pick an alignment, and that’s sort of it. There’s no guidance for how to use alignment in D&D. If you’re a new player, there’s nothing to tell you why you’d play good, evil, or neutral, just that these ideas are in the game. If you’re an old school player, you were probably just going to assume that everything worked the way it did in 3rd Edition whatever the rules actually say anyway, so.

But out of that lack of guidance, come the problems that WotC and the D&D community at large are trying to change. Without guidance, and just using the examples in the text, you get passages like this:

Or this one from Mordenkainen’s Tome of Foes:

And we’ve talked about why this language is harmful before, and in WotC’s diversity statement they acknowledge the kind of damage this language can use. But there’s still no guidance offered on how to use alignment, or why you’d want to in your game. Because, sure, you could use alignment to help shape your character and inform their decision. You could play a Paladin who is torn between desires that seem good, like protecting their family, or risking their lives and ignoring the danger that their child is in to try and save the whole world–or you might play an evil fighter who makes interesting decisions and whose nature sometimes gets the better of them and makes the story pop.

But tables where that’s the case are a rarity. For the most part, you see good and evil used to justify who you kill and who you don’t. Time and again, it’s “go kill the goblins/orcs/hobgoblins because they’re evil.” The good guys kill the bad guys and it’s a simple justification–but as we’ve seen that can easily be used to “other” people. It can lend itself towards some real world prejudice, and it makes for lazy storytelling, go kill the orcs because they’re threatening a village, or because their warleader gave you a scar in a duel and now you’re out for revenge, or because they stole the holy relic and you have to get it back.

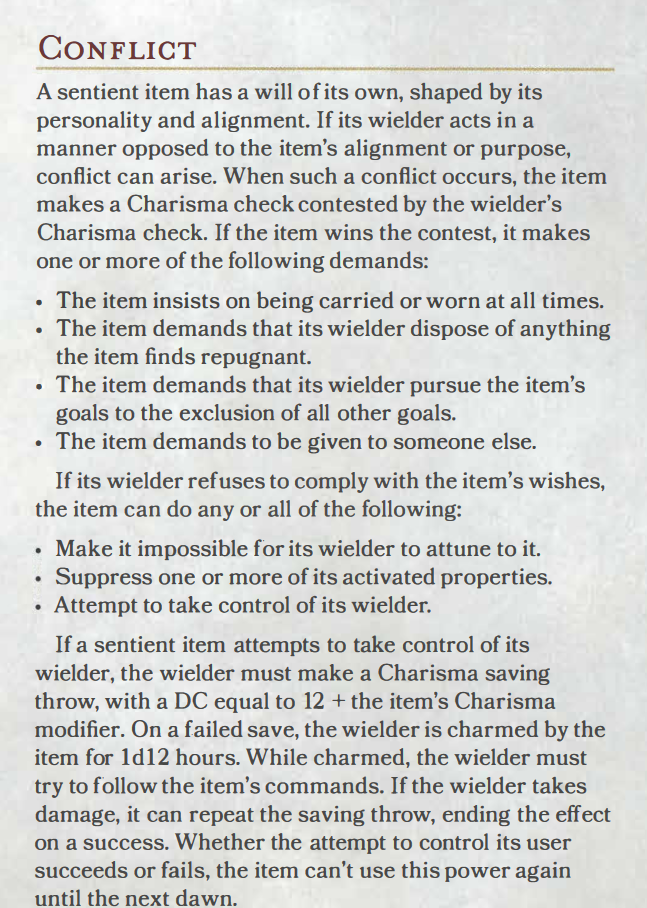

And in the game as it is now? There’s exactly one thing that checks on and cares about your alignment, and it’s not even your deities.

It’s sentient magic items. That’s right, your magic sword cares more about your alignment and how you act than your god does. As D&D moves forwards, questions like, what role if any should alignment play are important ones to ask and answer.

What do you think? How do you use alignment in your game? How would you change it?