How FASA Came Crashing Down – Prime

FASA went from publishing Traveller games to dominating the Mech market–but what happened to them? Here’s a look at their highs and ultimate lows. What Happens When The Shadows Fall.

FASA is a legendary publisher in the tabletop RPG industry, forged in the fire of the 1980s. From their initial work on Traveller to their licensing success with Star Trek, the early 80s were a great time to be at FASA Incorporated. But it was towards the end of that decade that they really hit their stride with two giants in the gaming world: Battletech and Shadowrun. Today we’re looking at how they went from ruling the cyberpunk and battlemech roost to becoming little more than an IP Holding Company.

From the outset, FASA has been a company focused on exploring worlds. Starting with Traveller, Freedonia Aeronautics and Space Administration Incorporated, or FASA Inc. has always been about digging into a setting. And while games like Star Trek and Masters of the Universe gave them a financial boost, FASA really hit their stride with their own IP. Well, theirs and Harmony Gold’s–and with that, let’s look briefly at the two giants of FASA: Battletech and Shadowrun.

Battletech

Battletech was FASA’s foray into another of their founders interest: giant robot anime. Inspired by shows like Macross, Fang of the Sun Dougram, and Crusher Joe, their game Battletech, (originally launched as Battledroids), wore its inspiration on its sleeve. And in 1985, that sleeve got them a cease and desist letter from Harmony Gold USA, producers of Robotech. This first brush with Harmony Gold was dismissed when FASA revealed that they had a license to produce these works from 20th Century Imports, in turn licensed by Studio Nue, who owned Macross.

It was enough to get Harmony Gold to back down… initially, but as you’ll see later in the article, backed down for the time being, this wasn’t the last that Battletech would see of Harmony Gold. It was enough to get the game launched, and when it launched it found an audience that was hungry for the giant robot tactical combat that Battletech was eager to serve up. With technical readouts showcasing new Mechs, and a crop of novels quickly being turned out, the Battletech Universe cast a wide net, hoping to snare as many players as they could with their setting, lore, and mechs.

You might scoff, but the storyline that FASA developed helped push the game into new directions. Innovation was always one of FASA’s biggest strengths–even with a success like Battletech or Shadowrun, the company never rested. They were always looking for new ways to expand the game and update the internal timelines. Battletech has some of the most visible examples of FASA’s storytelling style. In 1989, alongside the launch of Shadowrun, which would be a big enough challenge (and hit), they also released the 20 Year Update for Battletech, which completed the storyline of the Fourth Succession War and changed the whole game, moving it from 3030 to 3050 and changing the game as we know it.

This is the expansion that introduced the Clans, who came in from outside the Inner Sphere with ancient Star League technologies that they used to attack the Succession Houses with devastating efficiency. Everything about this book shook the game to the core. The Clan technology was a significant advance in both in-character storytelling and out-of-character game mechanics. You had pulse lasers and ER PPCs, and enhanced optics that all had rules in the game. And as it trickled out to the Inner Sphere they started copying it.

And while not everyone was pleased with the big, sweeping change to the setting (some fans continue to use Inner Sphere only rules to this day), it was a sign that the game was always moving. FASA learned a lot from the overarcing storylines of Traveller, and they wanted to bring that excitement to their game, wherever it showed up. And this storyline took Battletech into unexpected places–even virtual ones.

In August of 1990, the very first “Battletech Center” opened up in Chicago, with 16 different “pods” that were essentially a giant LAN party but with cool mech cockpit pods for each of the players. This was immediately a smash hit though, as in those days you couldn’t just boot up Battletech on your computer, and things like voice chat hadn’t become regular features, so if you were playing multiplayer games you didn’t know that your opponent was a 13-year-old obssessed with epithets and racial slurs and your mother. It was a quieter time. A peaceful time.

And over the course of two years, the first Battletech Center, part of Virtual World Entertainment, sold more than 300,000 tickets. By 1992, the Disney company took notice, bought a majority control in VWE giving it a financial shot in the arm that allowed them to open up 26 different Battletech Centers around the world.

In 1993, patrons in Battltetech Centers could compete against players around the country. And this is just the start of it. There’s a whole strange history to just the Battletech centers and how they pulled in celebrities like Cheech Marin and Weird Al to play characters in the Battletech world.

But that’s hardly the only venue that FASA was exploring. They pushed their book publishing into a whole new level in 1991, partnering with Roc Publishing to produce more than 100 books over a decade, starting with Legend of the Jade Phoenix for Battletech and launching the novelization of Shadowrun. If you ever read Never Deal with a Dragon, you’re benefitting from this agreement.

Perhaps the most successful venture for FASA was the second blossoming of the video game industry. As early as 1988 FASA was exploring the digital frontier with Westwood Studios’ Battletech: The Crescent Hawk’s Inception, a series launched for DOS and the Apple II, while the very first MechWarrior launched in 1989 from developer Dynamix. And that’s just the 80s. The 90s brought with them the home video game console boom, and Battletech made a splash on the SNES and the Sega Genesis with a port of MechWarrior, Battletech: A Game of Armored Combat, and Mechwarrior 3050. Meanwhile computer games like MechWarrior 2 and MechWarrior 2: Mercenaries shaped the way gamers viewed Battletech.

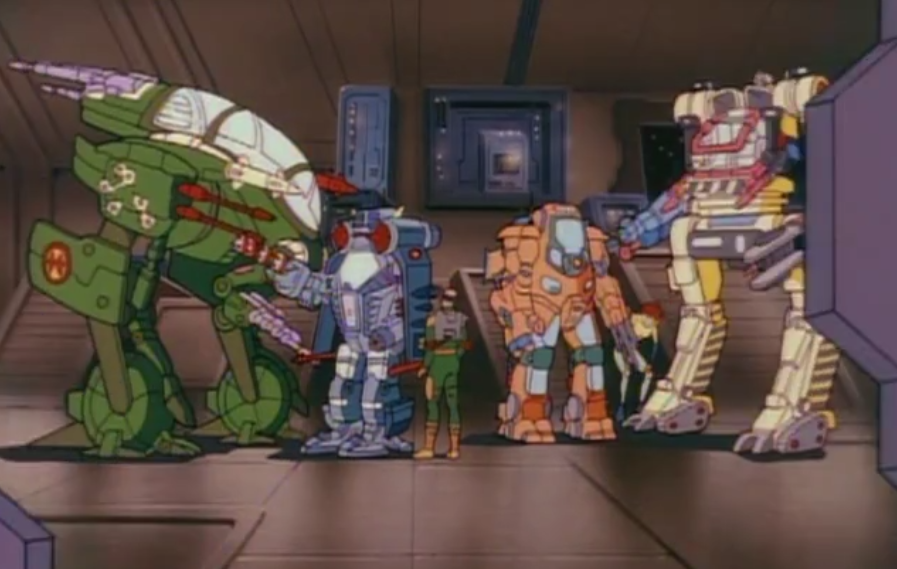

There was a Battletech Cartoon set in the Blood of Kerensky trilogy, making it one of two RPG franchises to have a Saturday Morning Cartoon:

Troublesome Toys

In fact, there’s only one place where Battletech had trouble expanding, and that was in the toy department. Battletech would eventually find a home with Tyco, but this opened the door to all sorts of trouble as competitor Playmates started work on another popular cartoon: ExoSquad.

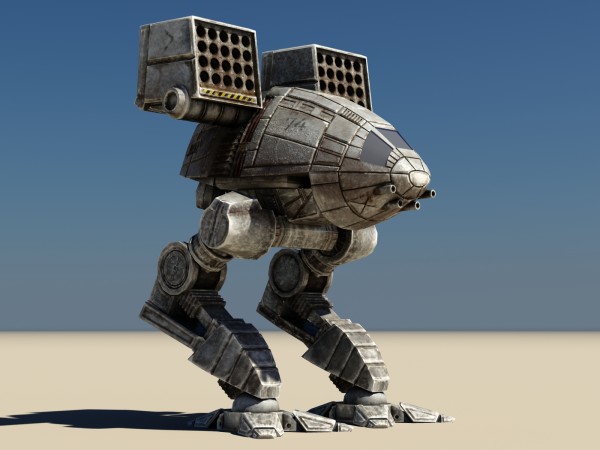

It all starts in 1993, when Playmates Toys releases their own line of action figures. FASA opened with a cease and desist letter, claiming that ExoSquad’s designs infringed on their IP rights (an ironic claim if you know the history), and that Playmates had used the MadCat design–which you can definitely see in the picture above. So FASA Corporation and Virtual World Entertainment launched a lawsuit against Playmates Toys:

FASA is the creator, developer, and distributor of various fictional universes, including BATTLETECH, which form the basis for board games, role-playing games, novels, and various game supplements. FASA also licenses the intellectual property and proprietary rights in its fictional universes to third parties for the development of interactive entertainment games, models, miniatures, merchandise, toys and other items.[4] Pls.’ Objs. & Resps. to Def.’s Reqs. for Admis. [hereinafter Pls.’ Admis.]

1. VWE is a virtual reality entertainment company formed by the creators of BATTLETECH to create and develop virtual reality games simulating adventures in the BATTLETECH universe. Pls.’ Facts

2. Playmates is a marketer of toys including a line of six toys featuring characters and vehicles found in the EXOSQUAD animated cartoon series.[5]Id.

6, 7, 9. The present lawsuit centers on *1339 Playmates’ alleged infringement of FASA’s intellectual property and proprietary rights in BATTLETECH by designing and marketing the EXOSQUAD toy line.

And this legal battle is a long, drag out fight, lasting a full three years–three years during which Playmates arranges a license with Harmony Gold to release Robotech toys as part of the ExoSquad line, which led Harmony Gold and Playmates to file a lawsuit all their own against FASA about the original Macross infringement. And while ultimately this lawsuit would be dismissed owing to Playmates trying to consolidate their suit against FASA with the one FASA brought against them, it was ultimately dismissed when a Judge found that no infringement had happened on either side:

The three year legal battle between FASA Corporation and Playmates Toys, Inc. over similarities between FASA’s BattleTech and Playmates’ ExoSquad has ended in a draw. On January 22, 1996, the United States District Court issued a long awaited ruling in the case which was tried before Judge Reuben Castillo in June of last year. In a lengthy opinion which detailed the development of BattleTech and ExoSquad, the Court rejected the claims of both parties.

FASA sued Playmates in April of 1993 for copyright and trade dress infringement and unfair competition after Playmates’ introduction of the ExoSquad prompted a FASA licensee to put the development of a BattleTech toy line on hold. Less that nine months earlier, Playmates had considered and rejected a BattleTech license but failed to return BattleTech materials submitted to it. Although the Court found “that there is a certain amount of similarity apparent between the BattleTech Mechs and the ExoSquad toys, especially between the Mad Cat design and the ExoSquad heavy Attack E-Frame design,” that “general impression of similarity” was not enough to award damages to FASA.

In reaching this decision, the Court also specifically rejected Playmates attack on FASA. Playmates had argued that FASA’s Mech designs were unprotectable because they were nothing more that general ideas common to the industry. The Court concluded, however, that “FASA’s Mad Cat and other BattleMechs and OmniMechs and the BattleTech Universe have incremental originality beyond any pre-existing works.” Noting that the “trade dress of FASA’s Mechs and OmniMechs have great notoriety and recognition among consumers of role-playing, board and virtual reality computer games,” the Court also determined that FASA had established protectable trade dress rights.

FASA Chairman Morton Weisman, disappointed by the Courts ruling on the ExoSquad similarities, was nonetheless pleased with its confirmation of FASA’s legal rights in BattleTech. “It is never easy for a small company like FASA to challenge a large company like Playmates, but FASA remains committed to protecting the integrity of the BattleTech Universe for its loyal and devoted fans and licensees. I am proud of FASA’s efforts in this case and look forward to many more years of dynamic development for BattleTech.

Harmony Gold’s own suit was refiled, and eventually that lawsuit was settled out of court, which resulted in some of the ‘Mechs being called the Unseen, still extant, but featuring no art based on their old designs. The fallout from this lawsuit would continue to plague Battletech across millennia, which is a rare distinction for a legal case. But Harmony Gold’s lawsuit came back in 2018 when HareBrained Schemes had Battletech and MechWarrior 5 due to come out.

As part of the settlement agreement, which included a non-disclosure agreement, FASA forfeited the right to use the images in question henceforth. This affected many core designs which have been described as the bedrock of the BattleTech universe at the time, and thus was a serious blow to FASA. All existing products featuring pictures of the Unseen, be it on the cover or within the rulebooks—effectively most if not all BattleTech publications—had to be discontinued, and while numerous other original designs remained that could still be depicted, this massively affected the BattleTech line. Miniature molds had to be destroyed as well.

Beyond the specific artwork covered in the Unseen lawsuits and settlement, FASA decided to summarily treat all designs as Unseen that had been developed out-of-house on general principle as a precaution. This included some designs that had not been covered in the court case, but shared the same background as the contested ones, but also unrelated third-party artwork to which FASA did have full rights.

Because this settlment was confidential, the issue of who had the rights to this artwork was vague enough that Harmony Gold would bring suit again when Catalyst Game Labs brought back the Unseen. Eventually this lawsuit would be “dismissed with prejudice” but that wasn’t until 2018. But let’s go back to the 90s for now.

Shadowrun

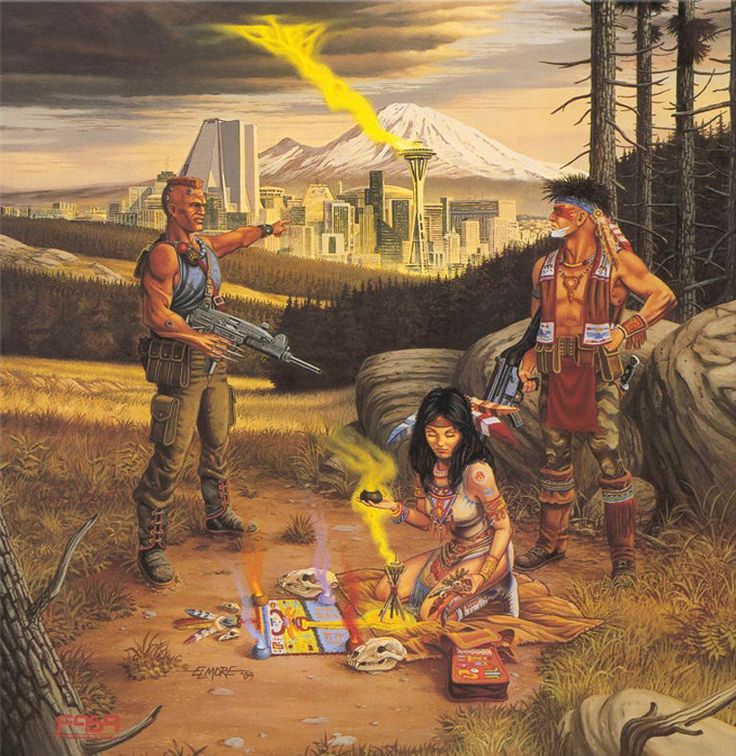

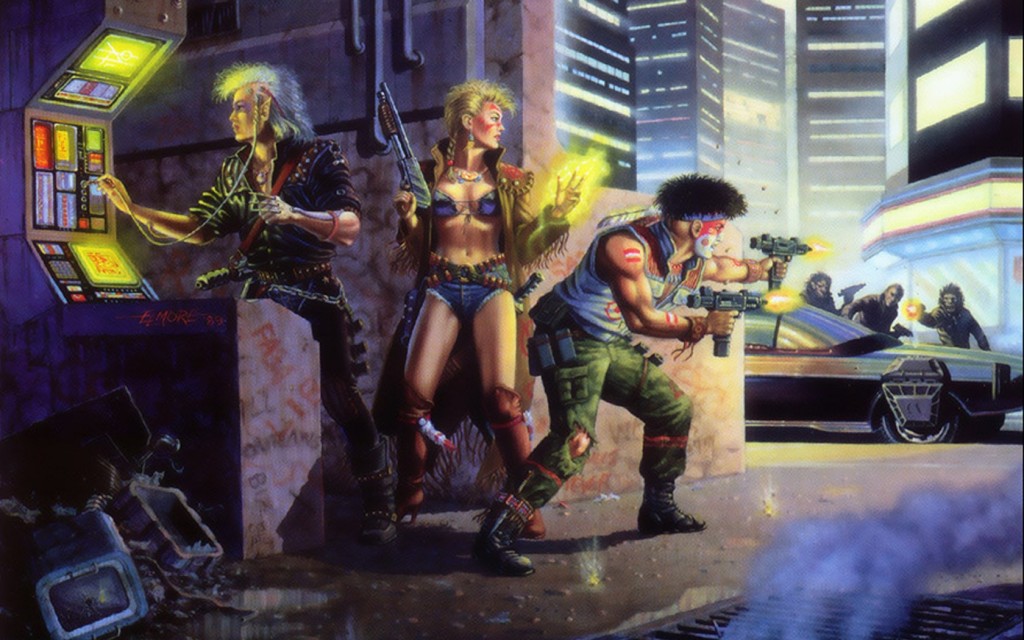

Because alongside the rise of Battletech, came Shadowrun. This is FASA’s other big title, and like Battletech, it hit at the right place at the exact right time. Where Battletech landed amid an audience hungry for anime action, Shadowrun landed right smack dab on an audience eager for an oppressive future dystopia where the line between man and machine brought about the commodification of human life as corporations ran amok over personal liberties. Guess everyone got what they wanted.

But at the tail end of the 80s, with novels like William Gibson’s Neuromancer kicking off the genre, Cyberpunk was a new, unexplored territory and Shadowrun manages to catch that wave. Shadowrun, which helps establish the scale of “mirrorshades-pink mohawk miniguns” is a fresh enough take that it captures all kinds of attention. With the addition of “elves on harleys” as founder Jordan Weisman likes to say, Shadowrun had something to offer to everyone, from fans of the genre to D&D players looking to try something new, but familiar enough, to people who just want to play a troll with a robot arm, Shadowrun exploded in popularity from the get go.

Shadowrun had just enough to distinguish itself when it came out–because it wasn’t the first Cyberpunk game on the market, that goes to R. Talsorian’s Cyberpunk, which is due for a new release sometime this year–but Shadowrun had an innovative feature with its fantasy pastiche. Shadowrun is a world where magic returns to the earth in a big way in 2011, culminating in an apocalyptic 2012 that ushers in the fabled 6th world of Mayan folklore, an era where magic informs as much of daily life as does technology. Trolls and Orks and Elves and Dwarves, it claims, have always been lurking in the background of humanity’s DNA, just waiting to explode–though it takes a massive plague to trigger it.

And of course it’s a hit. Shadowrun was not only a new game it used a new system–it’s one of the first “build your dice pool” games. Where most used a d6 or a d20 or some combination thereof, Shadowrun was all about stacking up as many d6s as you can and rolling to see how many beat the target number. While the initial system was a little unwieldy, this is the basic formula that informs much of the next generation of games, from White Wolf to Cortex, you can feel the influence of Shadowrun.

Considering that one of the initial designers on the system was Tom Dowd, who would go on to pioneer the mechanics in Vampire: The Masquerade, there’s little wonder of its DNA. FASA’s rapid expansion in all directions benefitted Shadowrun as well, with the aforementioned novel line quickly expanding the world, while video games–including two of the greatest video games (with wildly different results) to hit the SNES or Sega Genesis.

Shadowrun on the SNES was not exactly an authentic recreation of Shadowrun’s systems, but it captured what people loved about the setting–it told a story that wanted to roll out the world’s greatest hits, and with a soundtrack that remains killer to this day, it’s little wonder it did wonders. Sure, you play a Shaman with Cyberware, who also is a Decker, but that would be refined in later games.

Meanwhile, the Sega Genesis game was a much more faithful exploration of Shadowrun’s rules, though the heavy combat of the setting made it feel less like what people thought of as an RPG at the time, and more like a brawler. That said, it does have some of the best Decking in games to this day, and that alone makes it stand out.

And with a world like Shadowrun being big enough to support supplement after supplement, the game quickly made an imprint. With sourcebooks like Seattle and Berlin giving players a look at familiar locales done up in Cyberpunk fashion, with a lot of folklore sprinkled in, it’s little wonder it was so popular.

True to form, FASA’s plan of advancing storylines that update the game as they go was present here. There was a metaplot of insect spirits invading the world that was in the background of many of the supplements, and it culminated in wraiths invading from space to feed on magic and a saga that stretched back so far they had to create their own fantasy setting to present more of the backstory.

Earthdawn

Enter Earthdawn, FASA’s foray into fantasy. Earthdawn is basically a fantasy game where the apocalypse has already happened, Horrors from another world have ravaged the earth, civilization is just now recovering in the fourth age, emerging from the bunker-like dungeons to explore a world with sword and shield and spell. This game used its own skill system, experimenting with rolling everything from d4s to d20s, depending on how skilled your character was.

And FASA being FASA, the world was seeded with lore that would roughly set up events in Shadowrun, mostly related to dragons and a cadre of Immortal elves. Dunkelzahn aka Mountainshadow, is another great example of the bridge between the two gameworlds. However, as FASA would find out, sometimes that reliance on a metaplot can be as much a burden. Supplement after supplement ground the plot to a halt and tying things up for developers, and the overarcing story would get softly rebooted in later editions of Shadowrun, starting with 3rd.

The Fall

And amid this landscape, with both Battletech and Shadowrun performing strongly, FASA enters the tumult of the mid-late 90s. This is when the collectible card game wars start to happen–games like Magic: the Gathering threw the industry into disarray, as FASA had to shed licenses in order to try and weather the storm. Earthdawn weighed heavily on the company, though it faltered and would eventually be killed off. Meanwhile Shadowrun ran a big event to try and keep interest afloat with a massive presidential election–this culminated in the election of the great dragon Dunkelzahn (by player vote), who was then promptly assassinated, launching Shadowrun 3rd Edition and pushing the timeline to 2060.

This also set the stage to publish two of their own CCGs, unsurprisingly pushing both Battletech and Shadowrun into the CCG market for better and worse. As you might expect, both of these had enough success to keep the company pumping money into them, but never enough to justify the expense.

But even amid all of that, FASA still had some high marks ahead. In 1999 Microsoft acquired Virtual World Entertainment Group AND FASA interactive, which have both of these groups the opportunity to sort of regain control of Mechwarrior while the Xbox was looking for hot titles. This was a match that would eventually lead to MechCommander, but before then, FASA was quietly shuttering some of its least popular lines. Earthdawn was shut down in 1999, a few weeks after Microsoft acquired them–but then a few months after that, FASA was acquired by Deciper Inc., manufacturers of both Star Trek and Star Wars CCGs.

But then that deal fell through, and FASA floated, aimlessly for a while until the end of 2001, when it finally closed up doors. FASA exists in two places, FASA Corp, which holds the rights to Battletech and Shadowrun, and sold them to WizKids, and FASA Studios, which has been licensing some of the other rights FASA owns. In the ensuing time, FASA’s properties have traveled through WizKids, Catalyst Game Labs, and more. But that’s a story for another Prime.

That’s the history of FASA, which is still sort of around today, even if they really aren’t