West End Games: How An RPG Legend Expanded Star Wars’ Universe – Prime

From Paranoia to the expansion of Star Wars into what it is today, West End Games has one of the most enduring legacies of tabletop gaming.

In the world of roleplaying games, West End Games casts a long shadow. The tiny company made a journey from the beginnings of the industry in 1974, through the tumultuous 80s, where they were one of the few companies who could go ten rounds with TSR and have a shot at coming out ahead, to a strange, spiraling descent in the late 90s. Even then, West End Games had enough staying power in its properties to keep it going in one shape or another until 2017.

West End Games has an enduring legacy, with a surprising number of hits that outlast their own time in the spotlight. Their popularity let them tackle big names like Ghostbusters, Star Wars, and much later, Hercules & Xena. For a while, West End Games had tapped into that magic formula that makes all things possible: having enough money to have the infrastructure and pay people competitive rates. It helped that they started their tenure in the RPG industry by already being successful somewhere else.

Already having money has been the secret to pretty much every American success story, whether they’re an individual robber-baron, or a “self-made” tech startup that began in a garage with just a few hundred thousand dollars “loaned” from their parents. But unlike these folks, West End Games’ did actually earn their money the hard way at first. Like most things in the RPG industry, it all starts in the early 70s, with Wargames.

In 1974, West End Games was founded late one night in a campus bar near Columbia University. It rose out of the smoldering embers of a wargaming company called Morningside, based out of the Morningside area, that went “belly-up” and left behind a number of talented designers with an interest in seeing their work find a home. As one of the company founders, Scott Palter puts it:

We were a wargame company because I was a war game geek. A prior company I had playtested and designed for– Morningside– went belly up. It left a pair of finished but unpublished games, one mine and the other one I had done a bit of work on. I had a few bucks from my day job and teamed up with the remaining partner to publish. We got the name “West End Games” because the late night meet where we finalized the deal was at the West End bar near Colombia University. Between the four of us– 2 partners and 2 girl friends– we shot down every other name and I had to file as something. It went from there.

After that night, with a name in hand, West End Games began its life as a small wargames publisher. It started with all the usual wargaming fare, publishing a World War II simulation, Salerno, as well as Scott Palter’s game:: Marlborough at Blenheim.

Marlborough at Blenheim was a classic example of wargaming at the time. It was a recreation of the Battle of Blenheim, where a major battle in the War of the Spanish Succession was fought. The battle was where the swift, heroic action of Duke Marlborough turned the tide of the fight, driving back assailing forces from Vienna, changing the whole course of the war. This made it a natural fit for a wargame, but the recreation of the character of the battle was one of the things that helped West End game stand out.

Their most successful game was Imperium Romanum, released in 1979. As you might guess from the name, Imperium Romanum is all about the Roman empire. It’s a strategic board/wargame designed by Al Nofi, that attempted to recreate the various political, economic, and military conflicts that defined the Roman empire, giving players quite a bit of logistics and scenarios to work with. But even this initial success was still small potatoes in comparison to what they’d later find. By 1979, West End Games was still relatively small, boasting only two employees. And if not for fateful hiring in 1983, they might not have made it much past that.

However, in 1983, West End Games brings aboard Greg Costikyan, a veteran out of Simulations Publications, Inc., another well-known wargames company. SPI’s own story is a particularly labyrinthine one. It was a wargames company and magazine publisher that changed the face of wargaming as it tried to take the hobby over from Avalon Hill, the hobby’s other giant at the time. It’s a fascinating story as they were one of the factors that helped foster the creation of TSR, and ultimately, it was TSR that destroyed them.

It all comes down to the Dallas RPG and how that led SPI owing a great deal of money to their venture capitalists, which in turn led them to secure a loan from the then-flush TSR, who, not two weeks later called in their debt and sold off SPIR piecemeal, driving them out of business.

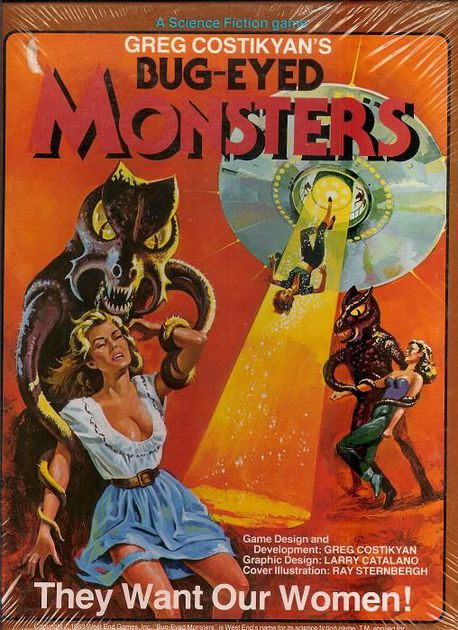

But that meant Costikyan had some well-earned experience that brought new ideas to the table and opened the door to new genres besides historical wargames. With Costikyan at the table, West End published sci-fi and fantasy board games, making a smash hit with Bug-Eyed Monsters. This game secured some much-needed growth for West End Games, but it was Costikyan’s next idea that would change the company forever.

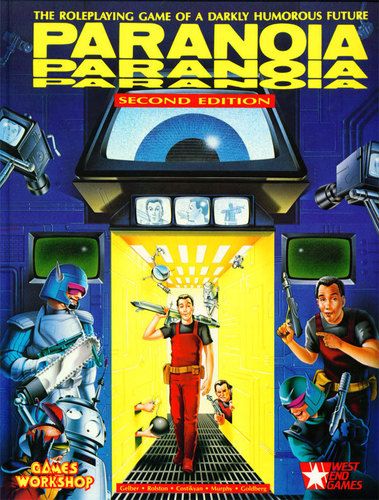

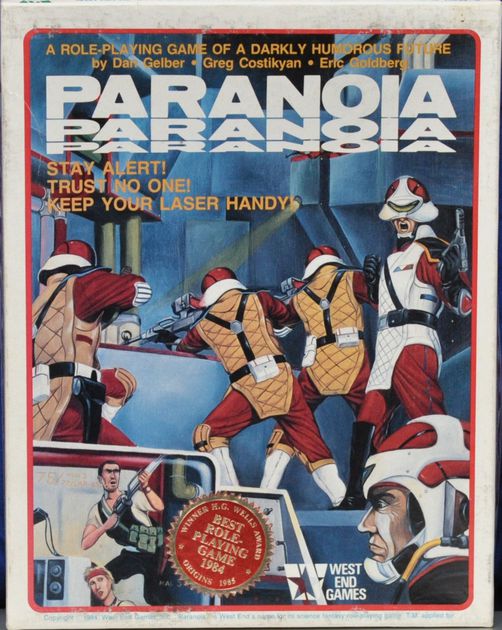

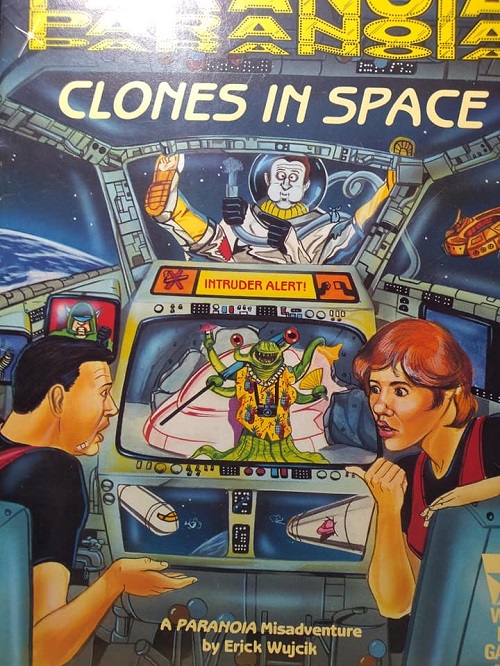

Because before Costikyan found his home at West End Games, he had been working on an RPG that you might recognize–Paranoia. Costikyan and his friend Dan Gelber had created the dystopian nightmare of a world run by a computer but interjected with a quirky sense of humor and a sort of cheerfully optimistic nihilism. Like most early RPGs, Paranoia began life as a game run for a small group of friends. Gelber had been running stories of Alpha Complex for his friends when both Costikyan and a fellow SPI-er approached about turning the game into something more, as he explains in an interview:

Okay, a guy by the name of Dan Gelber — a local-area gamemaster — came up with the idea for the game about three years ago [1981]. He ran it without any kin of system other than a few sketchy notes, improvising as necessary on the spot.. I played the game a couple of times, enjoyed it a lot, and thought the approach of a malevolent gamemaster in a malevolent roleplaying universe was a very interesting one. And so I suggested to Dan and to Eric Goldberg that it might be worthwhile taking Dan’s conception and turning it into a publishing game.

Subscribe to our newsletter!Get Tabletop, RPG & Pop Culture news delivered directly to your inbox.By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Of course, West End Games hadn’t made their mark at the time, but when Costikyan wound up there after TSR dissolved SPI, it seemed like a natural fit for a company that realized the Wargames market was starting to collapse. In the early 80s, Roleplaying Games looked like the next big thing, and Costikyan brought Paranoia to them at just the right time.

With its quirky sense of humor and dystopian fields, this was a smash hit. Paranoia was unheard of in the RPG world. In the 80s, RPGs were one of two things: they were D&D and its imitators like Tunnels & Trolls or The Fantasy Trip, or they were serious genre affairs like Traveller and Call of Cthulhu. Paranoia was something completely different. It called into question both ideas of setting and genre and leaned into the fact that it could appreciate the typical player shenanigans. To the point that it was designed for meta-gaming (which even back in the 80s was the source of many a fan-published thinkpiece), including mechanics for treason points gained if you, as a player, knew too much about what was happening:

The game system features a couple of innovations beyond the “Dramatic Tactical System.” […] For example your current standing with The Computer is expressed in “commendation points” and “treason points”; — In a touch of pure Costikyan devilry, the players — who are never supposed to know what’s going on — are neatly prevented from just sneaking a look at the GM’s books. Any player caught displaying knowledge of their contents immediately earns a treason point!

When you are asked “have you read Paranoia?” by someone you suspect you’ll be playing it with, your ownly wise response — even if you know all three books — is, “Just the Player Handbook.” The game influences your behavior even when you’re not playing it — a true “meta-game.”

Paranoia was something innovative and original, and it rests entirely on the fact that the writing brings out the atmosphere and tone of the game. Without the humor, and without a system that leaned on it, Paranoia would be just as flat as later attempts at “humorous” games. The game had a lot of innovations with it. Not only did it subvert the expectations for RPGs at the time–with both players and GMs encouraged to be playfully adversarial, and even unfair. It was also the first game to lay down a track in the more ‘storytelling’ focused games that would blossom in the 80s and 90s, influencing later titles than Ars Magica and Vampire: the Masquerade.

Paranoia’s focus on delivering a fun experience rather than creating a path for individual player success changed its approach to how players interacted with the games. Players could start plots and schemes against the others–as mandated by their secret society, which might give you anything from an individual quest to asking you to make sure that one of your fellow troubleshooters died. With Paranoia you had the first waves of what would later become the Splatbook movement, with secret society sourcebooks and other supplements that reshaped the way the industry worked

It’s hard to overstate Paranoia’s importance. It changed the whole paradigm of what an RPG campaign could be. It was a great experience, but it wasn’t designed to be played time after time. It’s not a long-running tv series, but rather a mini-series that you break out every few months. Same as Costikyan’s later titles, Toon.

But while Paranoia was a critical success that would go on to influence the RPG industry as we know it, it wasn’t the big commercially successful break that West End Games was looking for. As Palter puts it in an interview:

We got into rolelaying because Paranoia was kicking around looking for a home. The designers were in our extended social and playtesting circle. I wasn’t much into RPG’s due to an insane travel and work schedule from my main gig in fashion shoe imports. However I appreciated the humor and took a chance. It worked. Made a modest profit.

Paranoia was a flyer at humor. I was in love with the setting premise. It sold. Not blow you away numbers but healthy profit. OK. So to my mind RPG’s would sell. They were also less of a financial risk than board games. Cost less to create and MUCH less to print 5,000 or so.

So we did Ghostbusters.

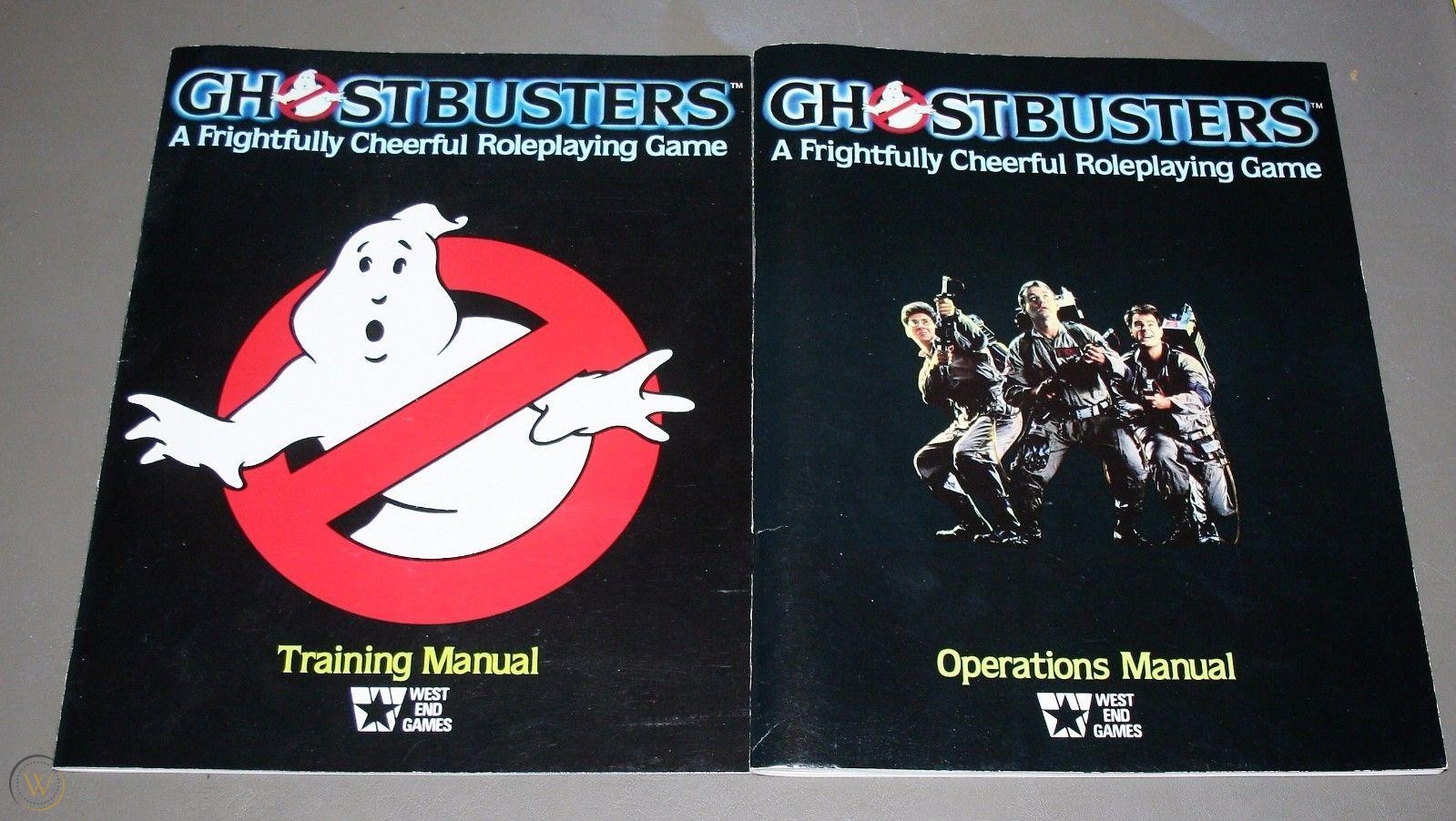

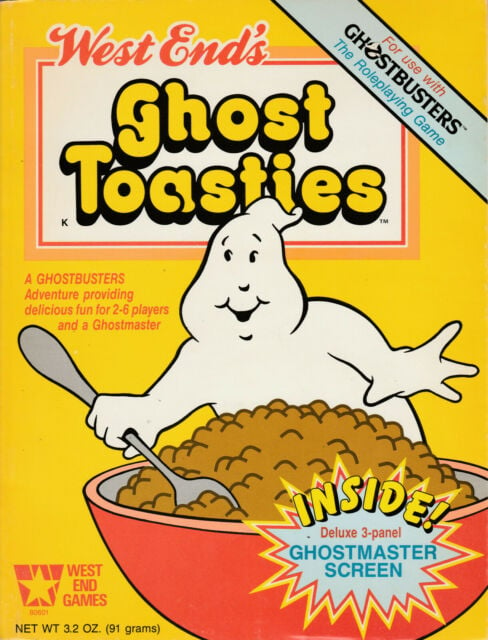

And that brings us to the first big thing for West End Games. With Ghostbusters, they had an obvious followup to Paranoia. It had everything that a distributor would want–a known brand, a gamble at a time when licensed properties were looked down on by the rest of the industry, it had an easy vehicle for humor–all it needed was a new system. It’s an interesting confluence of the industry at the time. The game was designed by Chaosium, experimenting at the time, with being a design house, but published by West End Games.

This was something of a risk, at the time. This was not long after FASA had lost some goodwill with its interpretations of Dr. Who or the declining Star Trek RPG. And TSR’s Indiana Jones RPG had done its damage and been scrapped, to the point where only a fragment remains as one of the more prestigious gaming awards now. Ghostbusters was not expected to be anything different.

But as Palter puts it, he was “always better at getting quality design work than I was at marketing, hence my fascination with licensing.” And that proved to be a surprise success here.

The system that Chaosium designed for Ghostbusters was a simple but broad system, and it laid the core for West End’s later successes. It’s one of the first games to experiment with additive dice pools, where players would assemble a number of dice to roll based on their skill. This goes on to influence later titles that use the exact same mechanic, such as Shadowrun or World of Darkness. But Ghostbusters had more to offer than just that.

Players could receive “brownie points” which let them influence the game to get their characters out of a tight spot or achieve some other narrative success. And the d6 engine proved to be commercially and critically viable. A fact that will soon become relevant.

Ghostbusters was also notable for being easy to just pick up and play. 24 pages of rules contained everything you needed to go on adventures–a format that many Indie RPGs follow even today. If you’ve ever played a quick game with surprisingly deep mechanics, you know what I’m talking about.

But West End Games had another RPG that would see it go down in history. And West End’s looming success begins a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.

As Palter puts it:

So to my mind RPG’s would sell. They were also less of a financial risk than board games. Cost less to create and MUCH less to print 5,000 or so. West End Games was supposed to be a side biz, not a money pit. So I rolled the bones on Star Wars.

I was always better at getting quality design work than I was at marketing, hence my fascination with licensing. I saw fantasy as covered by D&D. Traveller was there, but the universe didn’t excite me. Star Wars was the best universe out there. So I spent the money and we did it.

And when Palter says they spent the money, he means it. Especially since Palter’s approach was designed to generate a quality product:

Industry wisdom was that licenses didn’t sell. Public thought they were crap. Yes, many of them were but that wasn’t my approach. My approach was quality product. The license cost was marketing/branding. You still had to do first rate product – writing, playtesting, editing, art, layout. But the name bought you an audience that would try the first product. Hence betting a VERY large amount of money on Star Wars. Space Opera was a smaller market than fantasy but the niche to my mind wasn’t well filled by Traveller. Star Wars was even at ten years old the best known, most loved name. The trilogy was still all over cable TV so people kept seeing it. Even kids too young to have caught it in theaters.

But getting that kind of quality takes money. Even getting the license takes money. Fortunately, Palter had the family firm of Bucci Imports to help bolster them. Bucci Imports had already helped West End during hard times, but now, with Star Wars laying before them, Bucci Imports enabled West End games to offer an advance of $100,000 to Lucasfilm.

As they say, “to make a small fortune, start with a large one.” But it worked. Thanks to Palter and Bucci, West End Games secured the Star Wars license, and that changed both companies forever, as you’ll soon see.

Before that though, West End Games had some rocky-roads to travel through. Costikyan, one of the company’s best designers had been hard at work, making a template-based character creation system, allowing for archetypes without the restrictions for classes (things familiar to Shadowrun players, no doubt). But Star Wars–for all its innovation and polished design, hit a big stumbling block when Costikyan and fellow designer Eric Goldberg decided to leave West End Games in January 1987. Many reasons have been given for this: Costikyan and Goldberg wanted equity in the company, disagreements with management, the stories conflict, but ultimately everyone agrees that it came down to a conflict between Costikyan, Goldberg, and Palter. So the two left.

This left the game without its star designers. But that left room for a new face in gaming–Bill Slavicsek, whose name you’ll recognize from a ton of RPGs, including working on D&D (and being one of the designers who ultimately helped bring Keith Baker’s Eberron to fruition), and co-creating Torg, and a host of other beloved games. But back in 1987, the biggest thing Slavicsek had going for him was working on some of West End’s other products, and seeing Star Wars 39 times the summer it was released.

He was a huge fan of the movies, and it made him the perfect fit to launch the game. When they released Star Wars, Slavicsek had to communicate with West End Games. As he puts it, he told them that what they had was a cardboard movie town. They had the appearance of buildings and aliens and all these things–but none of them had weight. At the time, Twi’leks didn’t have a name, nor did Ithorians.

Facts that we take for granted, like Bacta tanks and detailed treatises on Ord Mantell and what exactly a proton torpedo is, hadn’t really been established. They were all just references in a movie that existed to provide flavor. All style. No substance.

Slavicsek and his team had to change that. Which they did with one of the best known Star Wars products: the Star Wars Sourcebook. It was an exhaustive resource on all things Star Wars. If you ever read anything in the Expanded Universe, or played through games and found something off the beaten path it can be traced back to this sourcebook.

When Lucasarts contracted Timothy Zahn to write the Thrawn trilogy, they considered these resources so invaluable and so canonical that they gave him a copy of the game and its sourcebooks to use for reference material:

The Star Wars movies themselves are always my basic source of ‘real’ knowledge. Supplementing that is a tremendous body of background material put together by West End Games over th eyears for their Star Wars role playing game. The WEG source books saved me from having to reinvent the wheel many times in writing Heir [to the Empire.]

And with this release, they had everything they needed for success. A strong license, a strong system, and equally as important, strong writing that breathed life into a world for an audience that was hungry to experience it. As Palter would later put it:

People really want to play out their media and comic book fantasies. Yes there is a market for generic worlds but there is a large one for worlds that already excite the imagination.

‘Cinematic realism’ matters. The less the rules make you think of them as rules/game the better. You should be doing scenes from the movie with yourself as the hero or villain. The rules work if they keep you ‘in the moment’ living the dream. They work if the end result at the table feels like an episode of the movie or show. Every time you have to come out of that dream to figure odds and minimax is a failure.

This game changed both West End Games and Lucasfilm’s trajectories. By the time the game was released the movies had been out for 4 years and nothing new was on the horizon. Along came West End Games and suddenly, the whole universe was expanding. As Palter puts it, even years later, “the movies never die, so people don’t forget them.”

All of that meant that West End Games was on the map. Sadly, it wouldn’t last–but for the next decade, West End Games was a rising star in the tabletop RPG world. How did they end up falling? That’s another story entirely. For now, we leave them, with their lasting mark on Star Wars and gaming firmly secured.

West End Games led to the Thrawn trilogy, which means that even in 2020, West End Games’ Star Wars is influencing canon.