D&D: Rime Of The Frostmaiden – The BoLS Review

Rime of the Frostmaiden wears fantasy horror to hide a magitech treasure race at its core. Is it a wintry wonderland, or will it give you the cold shoulder?

In the cold wastes of Frozenfar, everyone has a secret. But secrets have a way of outing themselves when adventure is in the air–that’s the promise of Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden, at any rate. It sells itself as a new adventure that plays up themes of horror, isolation, secrets, with a little bit of paranoia mixed in. And while that’s there if you’re looking for it, the adventure, overall, represents a marked shift in direction/tone we’ve seen growing over the last few D&D modules.

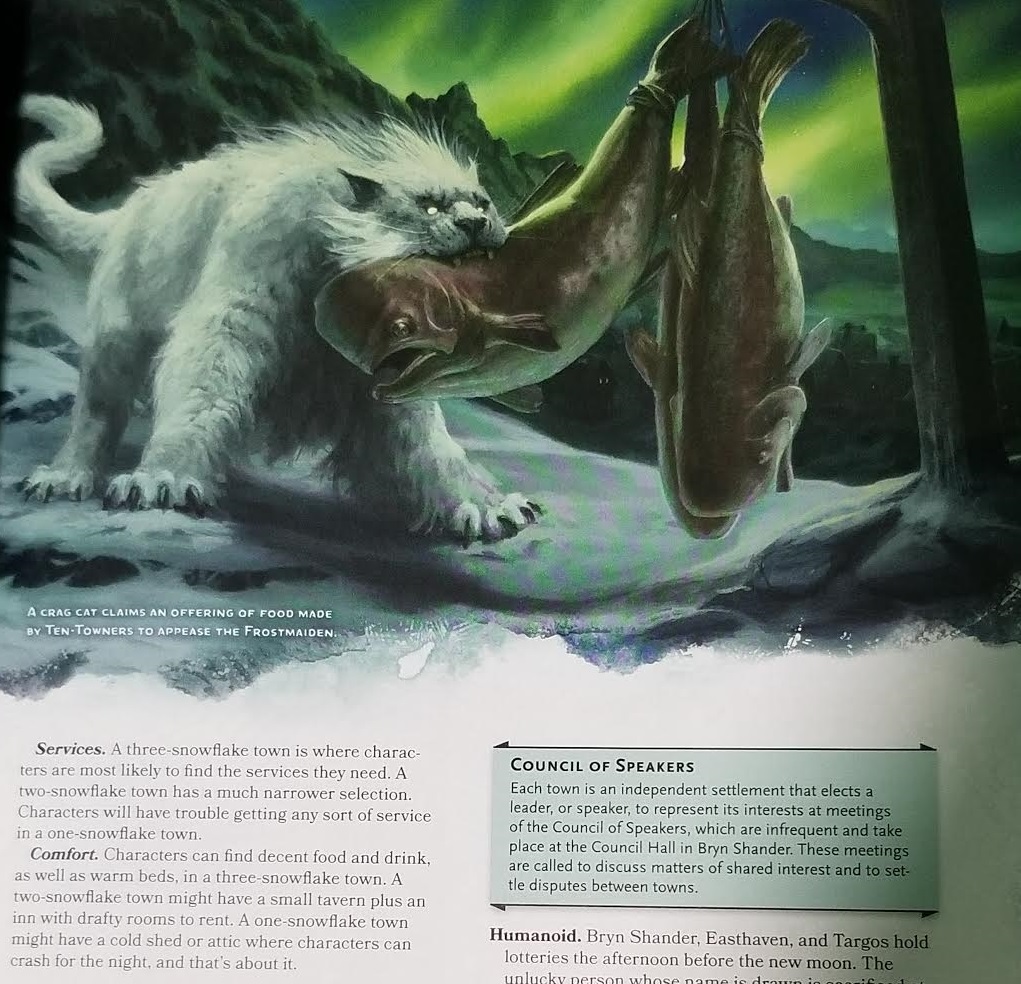

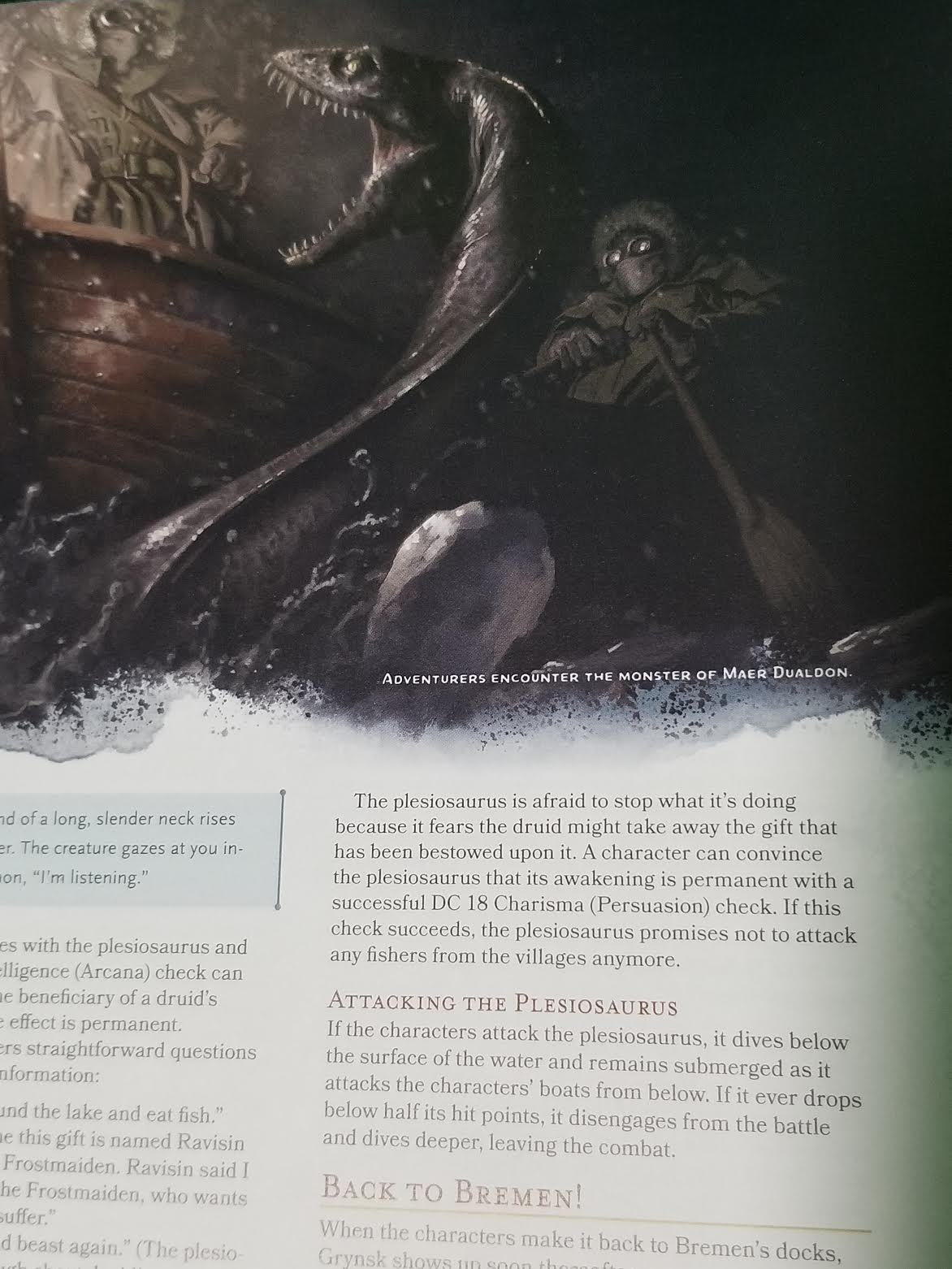

Simply put, Rime of the Frostmaiden feels like the first adventure module in another era. It’s an era that begins with Waterdeep: Dragon Heist and continues through Eberron: Rising from the Last War, Guildmaster’s Guide to Ravnica/Mythic Odysseys of Theros, and Baldur’s Gate: Descent into Avernus. One of the defining features of this era is a move towards more larger than life moments. Inside the books above and, in Frostmaiden as well, you’ll come across moments that feel like something you’d find in an actual play stream or podcast. And it’s little wonder, considering that streaming/casting shows are on the rise right now. Whether it’s racing on giant infernal war machines that are part machine, part demon, all metal–or dealing with an Awakened Plesiosaur, moments that feel meant for “good TV” abound in the game. Which isn’t a bad thing. Not by any stretch.

In fact some of the more over-the-top moments are among the standout features of Icewind Dale: Rime of the Frostmaiden. Seriously, this is one of the more whimsical D&D adventures if you take little more than a passing glance: you ride on the back of a magical Narwhal, deal with all sorts of magical nonsense like Living Spells gone awry, potentially even fight a goddess while investigating the magitech ruins of a past age. Not that there’s a shortage of serious moments either, but Frostmaiden is meant to feel fun. You might be asking, isn’t that a good thing? Shouldn’t all adventures be fun?

And you’d be right. They should. But this is an adventure that’s designed to feel as fun to watch/listen to/read as it is to play through. It’s a weird needle to thread, because it hits at a time when RPGs are approaching another evolution point. You have to consider, what is this adventure saying about itself? And in this case, it’s saying that the story of Icewind Dale is one that matters–but how it relates to the core rules of D&D matters less. Not to denigrate the work that the writing and designing teams have done here, Frostmaiden features some challenging encounters mixed in. There are places where the game pulls no punches. Auril herself, we’ve seen, is a multi-phase boss fight, and is an answer to the easy one and done encounter. But even then, Auril can be encountered at level 7, and is only herself CR 9.

It’s a new kind of D&D. This is an adventure that knows it has to present the cool iconic moments well before you “earn” them by reaching 20th level. Which nobody does anymore, if they ever did. Data has shown time and again that most campaigns end by the time you hit level 10, and more than 60% end by level 6. That’s where the writing comes in. The game reaches for the iconic moments of a D&D campaign, and largely delivers. You can feel the influence the diverse writing staff have had–there is a wider variety of encounters here than you’d find in your typical starter set. While you’ll still find your “goblin encounters” there are plenty more encounters that are designed from the outset with both combat and “interaction” in mind.

It comes back to the Awakened Plesiosaur for me, which is one of the first moments where the game resets your expectations. After outlining the stats of the plesiosaur and talking through the ways it might attack you, it also mentions what this plesiosaur has to say if your players should talk to it. And this is far from the only moment like it. Much later, as the party is exploring a magical laboratory, you can come across an arcanoloth who always refers to itself in the third person, carries around black licorice, and is attended to by a sentient albino giant penguin known as Kingsport which hands the players a note reading help me.

And it threads that needle. This could be a flight into whimsy for its own sake, but Frostmaiden has a purpose for its madcap pieces. They’re not just thrown in for “reasons” or “because, lol”, but rather they create this environment that begs exploration. While the book advertises itself with horror, it’s one of the best examples of what you can do if you want to focus on the crumbling pillar that is “exploration” in D&D.

It means you don’t have to wait for big moments. The expectations that players of low level can take on challenges far above their weight is plain as day in this adventure. You might have to fight a dragon construct that attacks a town, and is sort of a mini-adventure unto itself. Or you might have to deal with the inhabitants of a magical prison that’s been overtaken–and the game provides you with guidance for a variety of approaches. It doesn’t shrug its shoulders and say “you figure it out” when roleplay/social interaction is an option for encounters–it takes that into consideration and offers you some much-needed guideposts.

I’ve seen a review that calls this adventure “challenging” because it’s full of twists and turns. But I don’t think it is. It’s “challenging” if you’re used to approaching D&D as nothing more than an excuse to kill two goblins, then kill three goblins, then kill four goblins and a wolf, and then finally kill three goblins and a bugbear. It’s not straightforward, but it’s still linear enough that you can follow it. There’s room, much like in Tomb of Annihilation, for exploration, but it’s more at the beginning of the adventure, which does a good job of leading players to their characters.

The opening chapter of the adventure contains multiple different “starting quests” that are there to prime 1st level characters for the challenges they’ll need to face when the adventure begins in earnest. It’s like the first mission in a Bioware game where you go on an adventure and everything feels fine, but as you near the end of your quest, you start to realize things aren’t what they seem, and the next thing you know your life is forever altered as you’re pulled onto a collision course with an epic adventure.

That’s what Icewind Dale is. In many ways, it’s the starter set that the new generation of D&D players demand. It helps folks who aren’t professional voice actors find ways to get into character. On the starting quests, you’re given choice after choice to make to define your characters before you take them on the adventure. It’s the opposite approach to most D&D modules, including Dragon Heist, where the beginning is basically “you’re on this adventure, go.”

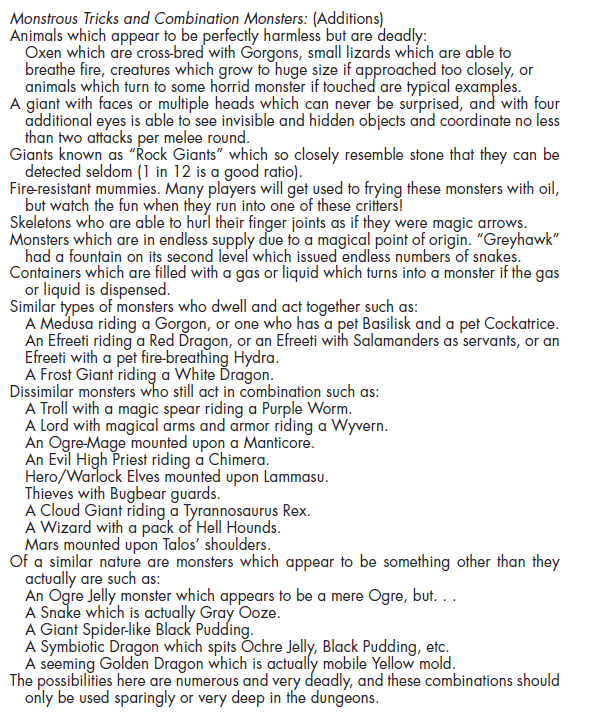

Here, it’s figure out who you are. Have encounters with dwarf bandits and haunted mines. Meet a variety of NPCs that give you an opportunity to play off of them. Honestly, I wish I’d had an adventure like this when I was starting with D&D. They’re out there–people brush off old school D&D modules as being dungeon crawls with little else to offer, but there’s a surprising amount of character in them. And if you look back at even the hackiest, slashiest dungeon crawls, the best ones, the ones that stick in your minds are the ones that try something different. Whether that’s finding a crashed spaceship, or fighting weird combination monsters, like these, outlined in the original Greyhawk campaign box:

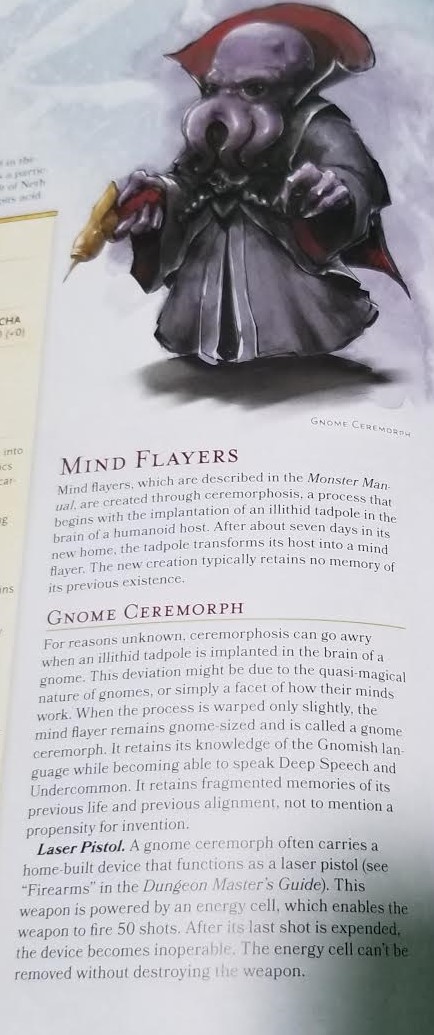

Look at the list, and you’ll find lots of over the top encounters that feel like the sorts of things you’d hear about from your friends, or watch on one of your favorite APs. These are held up as things to be used to make your dungeons fun. That’s where the reward was, finding fun encounters with things well above your weight class. Not fighting the same three goblin encounter time after time. Here you’re fighting gnome-sized mindflayers armed with laser pistols, and having a great time.

That’s what Icewind Dale delivers. It has that old school wild-style flare with a thoroughly modern design schema. It’s fun to read and fun to play and fun to talk about. It’s a difficult goal, and there are definitely places where Icewind Dale’s pacing can feel erratic, or where it feels like the PCs go to a place because they’re expected to, but those are few and far between.

Frostmaiden plants a flag in a new era. You only have to look at how it’s been promoted to see the ethos behind it. The book was announced by streamers, most of whom are streamers of color, the writing staff is 50% folks who identify as women or non-binary–but while that is sure to generate a big boost of warm, fuzzy PR friendly feelings, the fact remains that this rings a bit hollow in light of recent controversies. Many of the names on the credits for this book are no longer at WotC, having stepped down very publicly and very recently. And WotC is still under fire for mistreating their employees of color, and creating an environment where their voices don’t feel heard within the company.

So even as a new era opens up, the waters are murky. And the wind is picking up. RPGs are approaching an inflection point, and if WotC wants to, as they claim, support and advance the voices of marginalized folks to make their games more equitable and inclusive, they’ve got change along with the wind. But for now, there’s the cold of Icewind Dale.

Happy Adventuring!