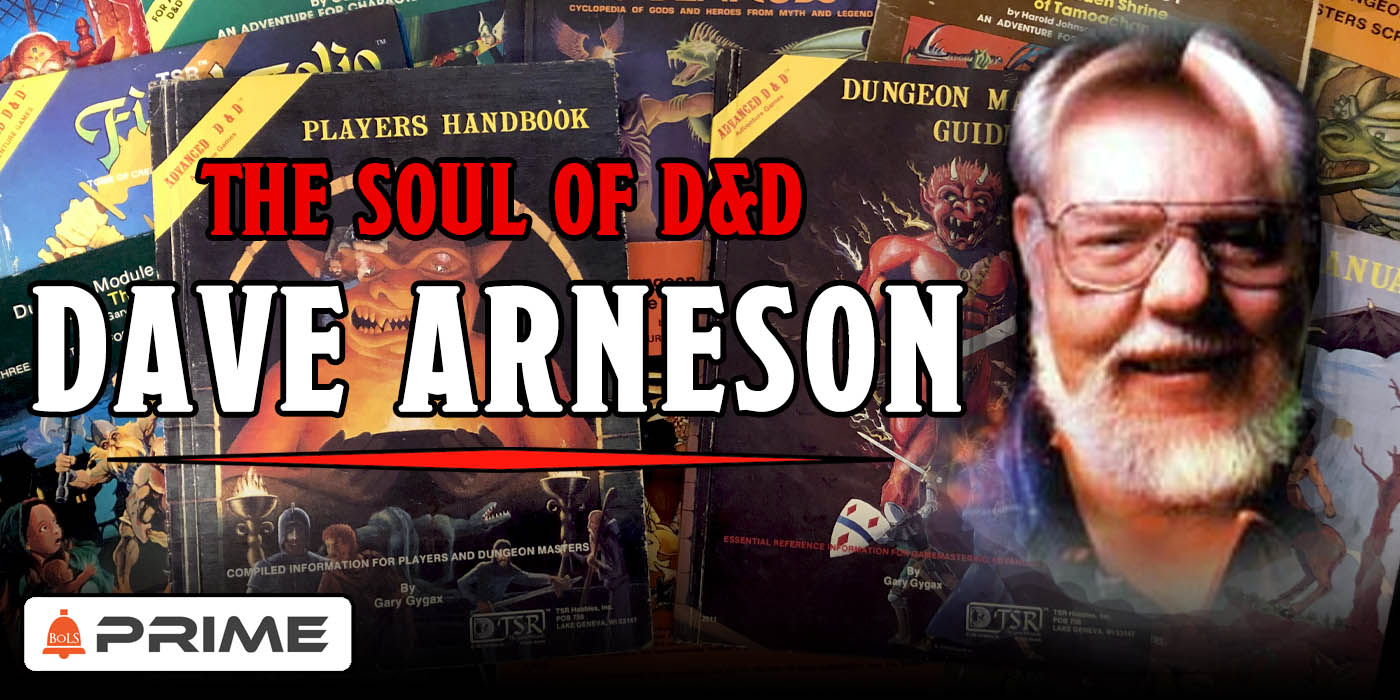

Dave Arneson helped make D&D what it is today. From DMs to campaign worlds, Arneson's legacy is clear, despite a bitter feud between the founders.

Dungeons & Dragons wouldn't be half the game it is without Dave Arneson. Literally. Arneson is credited with inventing "dungeons" so without him, the game would just be "& Dragons." From his early days working on the game/setting known as Blackmoor, to the co-creation of D&D with E. Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson left a big mark on the RPG industry. But for all that, he was almost ousted from the game he helped create, leading to one of the many lawsuits that cast a pallor over the early days of D&D. But legal disputes aside, Arneson's design gave D&D it's personality. If you've ever adventured in a dungeon, found a magic item, or experienced the boundless immersion that a good game of D&D can build, you've experienced Arneson's work. So where does it all begin?

As with most of the stories in the early days of RPGs, it all comes back to Wargaming in the early 60s. Arneson got his start with Gettysburg by Avalon Hill--a company, ironically, owned by Hasbro/WotC to this day--a classic Civil War board game that enthr...