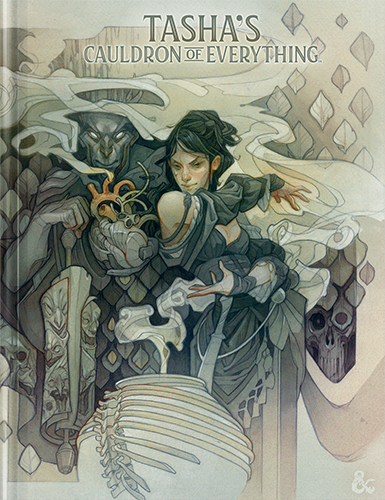

D&D: Tasha’s Cauldron Of Everything – The BoLS Review

Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything has rules that touch on everything from creating characters to running the game. But is it the shot in the arm 5E needs?

When you first pick up an RPG, there’s this moment where it feels like a whole new world is at your fingertips. Before you understand how the system works, before you “see the Matrix” of modifiers and stats that make the world tick. In that moment, it feels like you can be anything and do whatever you want. Eventually you realize, ‘wait, while I can play a Half-Orc wizard, it’s kind of shooting myself in the foot from the outset, because I don’t really get a bonus to my Intelligence, so I start behind the curve.’ There are some implicit archetypes built into the rules.

Halflings are quick and dextrous, they make great rogues or bards. Half-orcs are powerful and are at their best when making melee attacks. Elves make surprisingly good monks. Dwarves are clerics, fighters, or rangers and it takes work to do much else.

Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything looks to change that. In fact it looks to change the status quo for D&D 5th Edition. It’s not necessarily “5.5 Edition” but it plants a flag firmly in one direction, laying the groundwork with evolving rules for both players and DMs to learn. It’s a summary of pretty much everything the community and WotC have learned over the last six years of D&D: players want to customize their characters and don’t play to the highest levels; DMs are tending to run more story driven adventures than pure dungeon crawls; everyone sitting at the table is looking for tools to tweak the game. Even when they’re playing as close to the rules as they can, they long for flexibility.

Long time members of the RPG community will recognize much of what’s in this book. Terms like Session Zero and Hard/Soft limits (or Lines and Veils) are old hat to many players–Tasha’s Cauldron in many ways just codifies these common practices as a part of what’s expected in D&D. Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything feels like it’s a resetting of expectations for what goes into a D&D game.

Players and DMs alike will find useful guidelines that make gameplay easier, while offering up more depth in key areas. I think the best example of this can be in the massive overhaul to summoning creatures. Previously, spells like Conjure Demon or Conjure Woodland Spirits were sources of strife for either players or DMs as they let you summon creatures of a certain CR from available monsters. Which is fine, when you only have one book. But since the publication of the PHB, there are two books dedicated to new monsters, as well as new creatures found in every adventure that WotC puts out.

Imagine having to balance a new creature against whether or not a player will summon and/or transform into it. Now, the new rules operate a lot more simply: spells that summon a creature call up a single “spirit” which uses one particular stat block but can take on whatever appearance its caster desires. It’s a simple change that makes it easier to play, and easier to balance–as a result, summoners no longer have to spend their action commanding their conjured creatures.

It’s enough to make a Beastmaster ranger envious. Except they’ve fixed that too. There’s a whole section on Beast Master Companions that are alternate options for your animal companion. These can be brought back to life, they can take on a different form after a long rest, and they no longer eat up the ranger’s action to be told to do something. They still take a bonus action, which means that rangers will still find themselves deciding between casting Hunter’s Mark or something else.

The whole first half of the book is full of changes to every class. Fighters get a lot of attention, with new martial maneuvers and fighting styles offered. Warlocks and sorcerers find themselves with a lot more versatility thanks to a rule that lets them swap out spells whenever they finish a long rest. And as we’ve said time and again, this book removes the limits on racial ability score modifiers. You can make that half-orc wizard or dwarf bard and not feel like you’ve hamstrung your character before you even had your first encounter.

So it’s strange when the book does this hard work of resetting expectations and very clearly outlining the future of D&D 5th Edition (and beyond), that it’s all considered optional. It’s like WotC can see the stirring of the pot. They can hear gamers clamoring against a change to the status quo. Mention the mere idea that tying ability score modifiers to your race could be harmful, or that the language used for orcs borrows harmful stereotypes used on real-world marginalized folks and the pitchforks rise around the internet. If you don’t believe me, check the comment section. But that happens anytime you change anything. Even if it’s optional.

When Sara Thompson added a magical wheelchair to D&D as a free homebrew rule that anyone could use, the mere idea that it existed and that someone might use it drew chuds out from all corners of the internet to talk about how it’s utterly unrealistic to represent disability in a fantasy game with dragons and wizards and magic swords.

WotC is trying to dig themselves out from under the pall cast on the game over the past year. It started with an acknowledgement that some of the rules and language and portrayals of the game might have been causing harm–which is a great first step. But then controversy after controversy seemed to hit the company as marginalized employees spoke out or quit. Even folks on the executive team spoke out against what was happening.

Tasha’s Cauldron seemed like an opportunity for some real change to happen. And, to be fair, it’s here. Though the book doesn’t call them “RPG Safety Tools” (hey another phrase that stirs the pot), they’re in there. Just look for the section titled Social Contract and you’ll find common tools for keeping players and DMs expectations in line–including rules for how to set limits on what kind of content you do and don’t want to see in your game. Which, again, is something even the idea of was enough to get folks to say “I’d never play with anyone who wanted to use these.”

Divorcing race from ability modifiers is a huge step forward for the game. Play that kobold fighter all you want, or that gentle half-orc bard. But at the end of the day, the orc still makes savage attacks–it’s not perfect. It’s still drawing on the same language that WotC is trying to move away from:

But for all that, orcs are no longer always evil–no humanoid creature is. If you look vaguely human, you get free will. Which is great. WotC is at least making the effort to live their values. But, on the very first page in the book you’ll find big bold red letters that say IT’S ALL OPTIONAL and it feels odd given that much of the work here makes the game play better. And while the rules are always optional at your home table, Tasha’s Cauldron is the new best friend for every Adventurer’s League player. In WotC’s “official” organized play, these rules aren’t an option. You can create your character and swap your racial ability modifiers and proficiencies as you see fit.

There are rules for creating your own custom origin, though they feel a little lackluster. But they’re still a great jumping off point. This book goes so far as to give players and DMs what they want–more ways to play the game they love. And for their part, WotC has made the rules for changing your racial ability modifiers available for free. You can find them here.

And with 22 new subclasses (which we’ll be going into in a lot more depth outside of the official review), and new rules options that make each class feel fresh–this book doesn’t feel optional. It reminds me a lot of the revised 2nd Edition Player’s Handbook, which had in big bold red letters at its front: THIS IS NOT 3rd EDITION.

This book isn’t 6th Edition, but you can see it from here. It reminds me a lot of the release of the Book of Nine Swords, which introduced a whole new paradigm for 3.5 Edition D&D. It gave more power all around to martial players, and added in new options for everyone to play with. That’s what Tasha’s Cauldron feels like. It’s just as paradigm shifty, but a lot more reined in.

Should you buy it? Absolutely. If you’re playing 5th Edition, the variant rules alone are worth it. They are the course corrections that every table wants, whether they know it or not. They make the game friendlier to newbies, and give veteran players the flexibility they have been craving. The new subclasses are potent additions to the game, and while there are one or two balance issues, for the most part they’re fun and functional. The DM tools are a godsend, and I wish I’d had them when I first started playing 5th Edition. Each of these alone is worth a deeper look than this overall review can give.

So that’s exactly what we’re going to do. Throughout the rest of the week, we’ll take you through exactly what’s in the book, giving you a look at subclasses, new spells, and more. Stay tuned.

Happy Adventuring!