RPG: The World Of Darkness’ Mysterious Beginnings

White Wolf emerged from the shadows of an RPG crash with a game that would slake the thirst of many a gamer for something darker. But where did it all begin?

The 90s were a decade of transition. Coming out of the cocaine-fueled orgy of greed, slicked hair, big shoulderpads, and New Wave music and leaning into the era of Grunge, Gen X disaffected irony, flannels, and Nu Wave (ovens). Couple all of that together with the stark changes in technology that define the era almost as much as Will Smith blockbusters releasing on July 4th weekend.

After all, in the 90s, you had the beginnings of the dot com revolution, and with it the very beginning of the rise of geek culture, for better and worse. After all, the 90s is a decade haunted by the shadow of the Y2K bug, the rise of the internet as a tool not just for nerds but for horny nerds, and games becoming much more mainstream than they ever had been. Geeky interests like comic books were undergoing transformations as the four-color superhero books everyone was familiar with got darker and edgier.

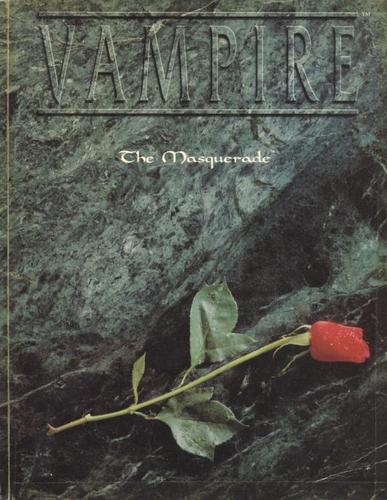

Gritty reboots were the order of the day–and it’s perhaps because the 90s were right on the edge of one milennia into the next–that everything in the 90s was at least a little edgy. And nothing is more edgy, not even a pizza cutter, than the World of Darkness. When Vampire: the Masquerade came onto the scene, here was the game that planted its feet firmly and declared that it was for adults. Well. Mature teens. Full of leather and lace and art that bordered on the erotic, Vampire the Masquerade was a huge departure from the fantasy adventures that had defined the previous decade.

And the publisher behind it all, White Wolf, had come from the unlikeliest of places. Like most things that are iconically 90s, it actually got started in the latter half of the 1980s. The growth of the RPG industry had hit a “slow period” which is to say it had a bust, not quite as bad as the video game bust of the early 80s that nearly tanked the whole industry, but it was bad enough to send a number of smaller publishers out of business. But it was still a small enough industry that there was frontier for new designers–and so it was that the founders of the White Wolf, Stewart and Steve Wieck, then in High School, wrote an adventure for the game Villains and Vigilantes. To their surprise, it was accepted and published, which bolstered the brothers and encouraged them to take the next step: publishing for themselves.

To our surprise it was and that served as a validation that we could get our material published in the RPG field and maybe someone would even enjoy reading it. It was a tremendous rush to see the final printed book with the text brought to life in art by Patrick Zircher. That sort of rush, a sort of vanity press type feeling really, was pretty addicting. We wanted more of that. Plus, while we never did it for the money, since Stewart and I were both getting minimum wage at Burger King at the time, even the modest amount we got paid for writing The Secret in the Swamp was a thrill.

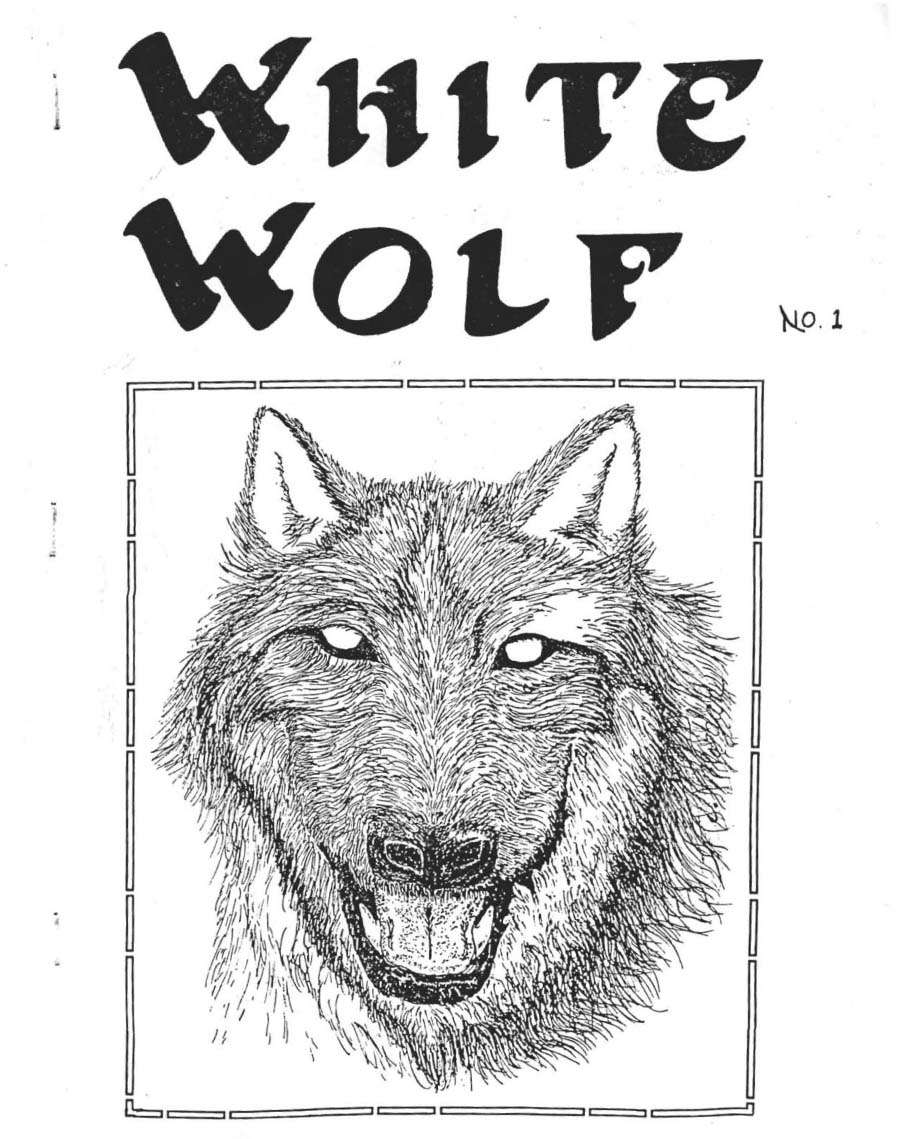

Stewart just came up to me during class break during high school one day and said “Let’s start a magazine,”; I said “Sure”; and we got to work that night on the first issue of what would become White Wolf Magazine. We still don’t have those early issues of White Wolf Magazine up at DriveThruRPG or RPGNow yet, partly because I’m not sure I want people reading my high school fiction attempts

And so it was that White Wolf began. In 1986, White Wolf #1, published by White Wolf Publishing emerged into the world. At the time, it was just a photocopied, stapled fanzine, entirely done up in black & white, but that was the humble origins of the eventual publishing giant. By issue #4, the magazine had a much more professional tone, and by issue #5, they had found distributors, which kicked White Wolf out into the larger world.

In fact, it’s here that Rich Thomas gets involved, answering an ad in Dragon Magazine. Thomas, who would become the eventual Creative Director at White Wolf got his start as a staff artist with issue #7 of White Wolf, and by issue #11 at the tail end of 1987, had become the magazine’s art director. After a successful Gen Con and the distribution of nearly 10,000 copies of their magazine, it was clear that White Wolf was on the rise.

As an independent magazine, White Wolf could do what rival publications couldn’t. It dabbled in the Indie RPG sphere, at the time. White Wolf covered games like SkyRealms of Jorune and Ars Magica, as well as shining a spotlight on RuneQuest. These moves took it away from covering AD&D which had been most of the early days of White Wolf. Again, that should give you an idea of just how big D&D is in the industry. So for a breakout like White Wolf to find success with so many other properties was a powerful motivation to keep the company growing. And grow they did, looking for ways to publish RPGs of their own.

As the 1980s came to an end, and 1990 dawned, Lion Rampant, a new RPG company founded in 1987, came across White Wolf Publishing’s radar. White Wolf came to their aid after Lion Rampant lost their initial funding, and this brings Mark Rein-Hagen into the fold, bringing with them Ars Magica, and a bevvy of talented designers with them. After the merger of the two companies, White Wolf Publishing became simply “White Wolf” and at the beginning of 1990, a dark new era dawned.

Ars Magica was the alternate fantasy game, but designer Rein-Hagen wanted to step away from fantasy, playing with darker themes. As the story goes, work had begun on a game called Inferno that took place in Purgatory, where players were taking on the roles of characters who had died in other campaigns. But, before the manuscript could be finished, a transformer exploded, and in the aftermath of this, the lone manuscript for Inferno was destroyed. And after that, the project was abandoned, because you only get so many smite-adjacent experiences before you actually get smote.

But on the road to Gen Con ’90, the White Wolf team decided to take the dark, brooding themes of their cursed purgatory game, combine it with a burgeoning new genre, Urban Fantasy, and start with a whole world of linked games. If you’re new to the franchise, the World of Darkness is akin to the Marvel Cinematic Universe–it was a series of different games that all used the same underlying mechanics. And it all began with Vampire the Masquerade.

Now, you can look at the leather clad, sexy vampires of Vampire: the Masquerade and see the resemblance to Anne Rice’s work. In fact, it was initially conceived of as an Anne Rice RPG, but White Wolf decided to create their own new gothic horror game. And in 1991, White Wolf had its befanged new baby ready to be published, and with it began a marketing blitz that dwarfed other efforts–up until 3rd Edition came along nine years later. It launched with a 16-page full-color glossy pamphlet full of art and mood-setting words. The gothic tones of the game were relatively new to RPGs at the time–there had really only been one other place that RPGs delved into darker territory before (at least with any degree of success): the world of Ravenloft.

White Wolf had a lot to establish with Vampire: the Masquerade. The initial hook was strong, but breaking any audience away from D&D is no small task. And even in the 90s, with TSR in decline, it was still the ruler of the roost. So White Wolf had to lay out their theme clearly:

She passes me by with a quick glance into the alley. I break away from the shadows. An arm’s-length away, I can hear her heart pumping.

AdvertisementI have become death, the destroyer of souls.

Gliding toward her, the smell of her life-plasm waifs over me, arousing me She is only inches from my caressing touch. My mind screams with lust.

NO!

This short vignette kicked off Vampire’s pamphlet. Again, you get the full Anne Rice treatment. Cold, inhuman predators in erotically-charged situations. This was a more mature game. D&D had its harlot tables and the occasional adventure that got them in a bit of hot water, but this was a world of sex and violence and angst and politics. It was a game not about delving into dungeons, but about navigating the complexity of a vampire court. And it was the first big game to come along and center its experience on “storytelling” instead of just fighting monsters. This was a trend among indie games at the time–a trend that continues to this day–but Vampire had the biggest budget, the best marketing, and the best design that the 90s could throw at the industry.

Ironically, Vampire’s success owes much to Shadowrun. The other divergent RPG at the time. Shadowrun’s mechanics are writ large in the DNA of the Storyteller system. Comparative dice pools–that is, dice pools where you roll dice and see how many succeed, had their first mainstream success with Shadowrun. And when Tom Dowd, co-designer of Shadowrun joined with White Wolf, that same mechanic carried over. Though Vamprie uses a d10.

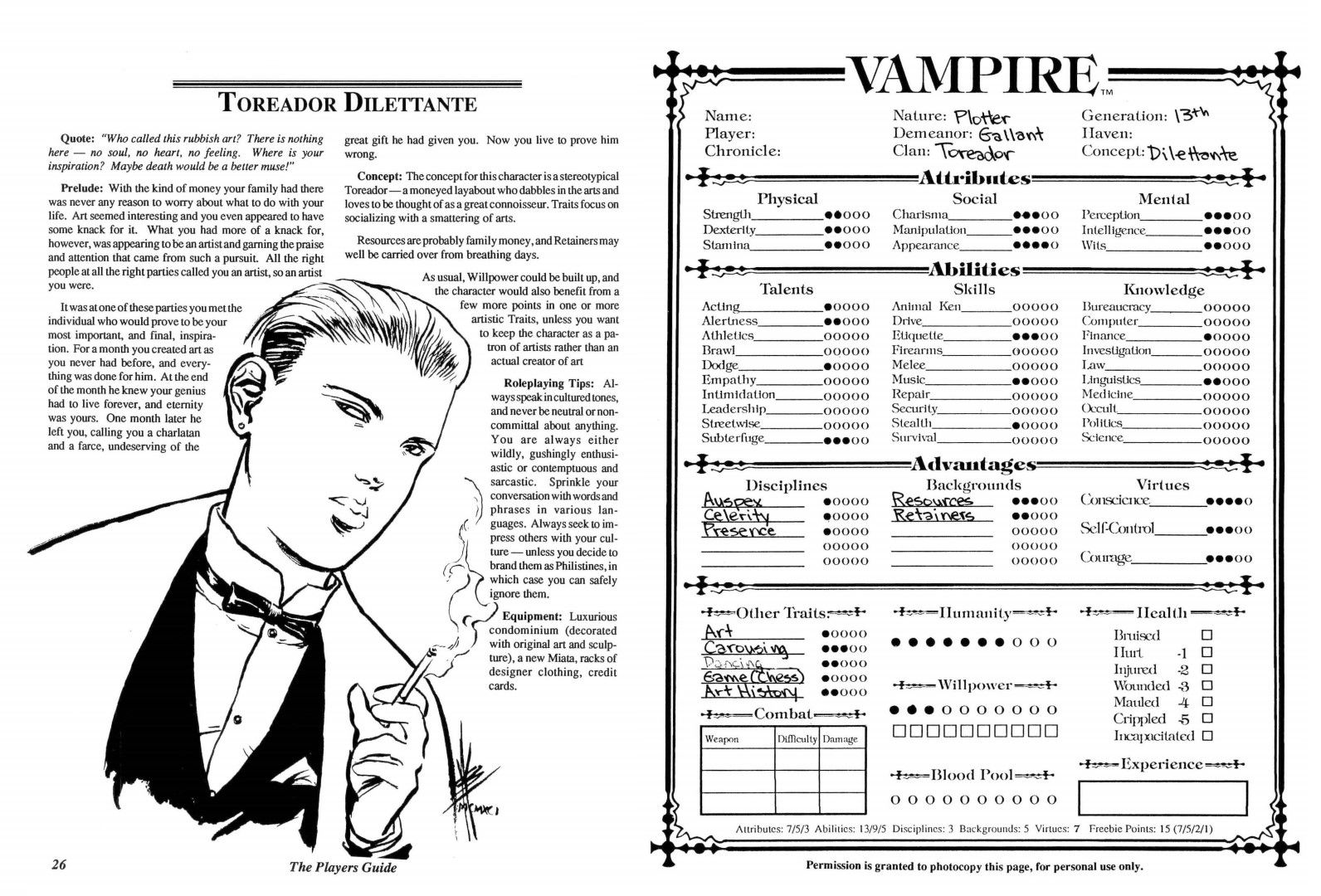

Also, you could argue that much of Vampire’s success came from its accessibility–which is a weird thing to say because it’s dice math is some of the most heavily obscured, and unbalanced system work out there–but, the meat and potatoes of creating a character are easy to digest. Skills and abilities had a finite cap. In fact, mostly characters existed as framework for the other signature of Vampire–disciplines.

Disciplines are the bread and butter of a Vampire character. These represent the supernatural abilities of vampires, like hypnotizing mortals with a gaze, or the ability to fade away into shadows or to move with supernatural swiftness. Honestly from 10,000 feet up, Vampire: the Masquerade was basically a superhero game with drama built into the setting.

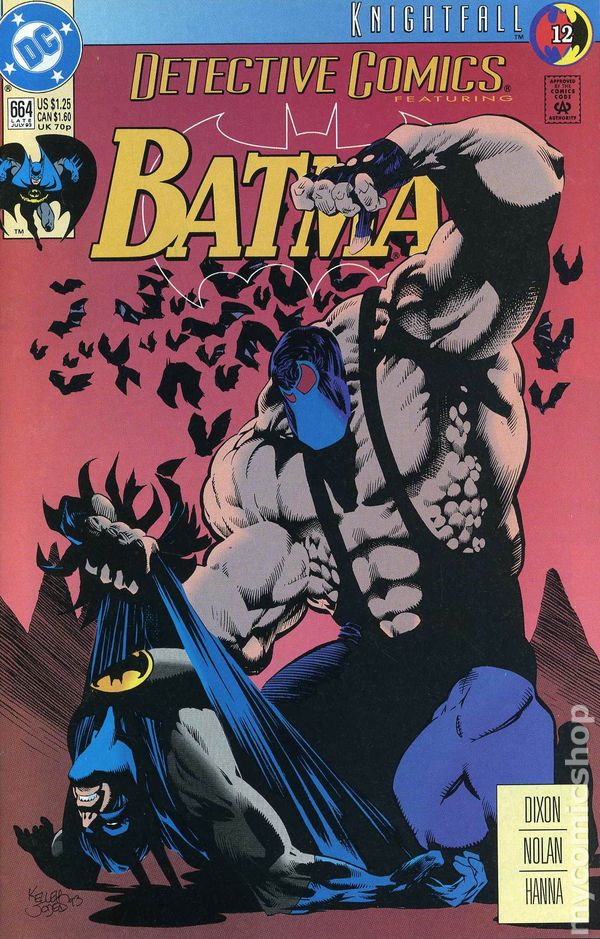

And that satisfied players. Look at where superhero comics were in the 90s. This is the time of gritty comics and pouches and guns and Cable. A brutal, brooding era that saw things like Knightfall come along:

And having a dark superhero game, basically, where you have the dramatic tension and sensuality of the 90s club aesthetic meant that you could really cater to players in a way that games like D&D couldn’t. It gave them a new playground and sort of established a baseline rule that carries through to games today. All players really want is to be able to describe their character, and have what they’re playing matter mechanically, and then to be able to pick out cool powers or moves that they can do based on this. Games like Apocalypse World and Quest draw on this tradition.

My very first game of Vampire: the Masquerade, when I was in high school, had more in common with superhero stories than it did with any Anne Rice novel. A lot of folk’s games were like that. But whatever style you were playing, it was clear, Vampire had found its niche. And with the ground-breaking success that Vampire: the Masquerade found, it was clear that White Wolf had a hit. So they followed quickly after with four new games to flesh out what we know as the World of Darkness. After Vampire: the Masquerade, came Werewolf: the Apocalypse, Mage: the Ascension, Wraith: the Oblivion, and Changeling: the Dreaming.

Each of these books had their own lens into White Wolf’s urban fantasy world. Werewolf brought the shape-shifting rivals to the vampires to the limelight and cast them as protectors of the earth, or Gaia, and it focused around what that corner of WoD looked like. Mage, on the other hand, was all about drawing on modern mysticism and hermeticism and putting that in a game about people trying to hold onto power and decide what to do with knowledge.

Wraith was all about death and remains an underrated masterpiece if you can find people to play it with. It’s definitely not for everyone, but it really played to its themes. Moody to the extreme, Wraith has players take on the role of the dark side of another character–so you’d have your ghost, and someone else at the table would try to tempt you down the evil path.

And Changeling was a bright contrast to the gloomy darkness of the rest of the games. It focused on the Fae and, as you can imagine, brought a whole other crowd into the fold of the world of darkness.

But that’s not the only innovation that White Wolf made. They knew their game was a roleplay-centric game, and so, to help support this they launched a whole system of LARPs. Though they weren’t the first ones to do so, they were one of the biggest organized LARPs. Minds Eye Theatre, which is still ongoing today, gave many young students a chance to wander around a college campus after dark, dressed up in gothic clothes for a few hours before finding a Denny’s to eat at after answering Campus Security’s questions.

Again though, this was a hit. It remains one of the most beloved parts of Vampire or the rest of the World of Darkness. Over the first five years, White Wolf could basically do no wrong. They created whole worlds and new ways of publishing them. Their initial years were all about innovation and expansion. They popularized the “splatbook” which is a common phrase for a book that’s all about one specific race or class or clan or something. If you’ve seen a Complete Elf or Complete Warrior guide, that’s a Splatbook. And White Wolf made one for each of their Vampire Clans, each of their Mage traditions. And in the background of all them, they wove together a giant, overarching metaplot, which for a while, worked to keep their story moving forwards.

But what really sold the deal was the push into the player side of things. No matter what you play, you needed a splatbook. They kept their publication in the hands of the largest part of their game. Campaign setting books and Adventures, TSR’s purview, were great, but they only appealed to DMs. White Wolf wanted to have a much broader appeal. Which carried them out of their humble beginnings, and into the establishing of an RPG empire. Over the rest of the 90s, White Wolf would endure where other companies failed. They outlasted TSR and many other giants before hitting the doldrums of the dot com bust. But for now, we leave White Wolf as we most remember them. Full of the ennui and innovation of the 1990s.

Now I guess I should go dig out my eyeliner and Bauhaus albums…