How Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay Did What D&Didn’t – Prime

In an age of both dungeons and also dragons, one fantasy roleplaying game carved a niche that stands to this very day: Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay.

Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay managed to do the impossible back in the halcyon days of the mid-late 80s. It actually carved out a niche and withstood the test of time when D&D was at its peak. Just when AD&D was at its height, right before the dawn of 2nd Edition, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay managed to carve out a space in the fantasy gaming scene. It earned not only an audience but a reputation as well. Not long after, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay ended up with what is widely regarded as one of the best RPG campaigns from the early days, The Enemy Within. And it’s been pretty much active in the RPG scene ever since.

But where did it come from? How did WFRP come to pass in the first place? To answer this, we need to step back to the year 1986, when Games Workshop tested the waters of the roleplaying industry on its own. GW was no stranger to fantasy or to RPGs–in fact, in the early days of White Dwarf, you can find many a D&D monster that’s considered a beloved classic to this day, This includes the Gith and Githyanki.

It seemed only natural that GW would want to publish a roleplaying game that drew upon the in-depth lore of their own fantasy setting. And indeed, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay was originally intended to be supplementary material for Warhammer Fantasy, to help flesh out the world. Which wouldn’t be the first time an RPG successfully fleshed out a previously established world.

One only needs to look back at West End Games’ Star Wars a few years prior to see the principle in action. And so, in 1986, Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay was published. It was popular enough in its own right, due in no small part to its unique setting and its unique system. The two are intertwined, with the mechanics helping to deliver the same narrative that the setting promised.

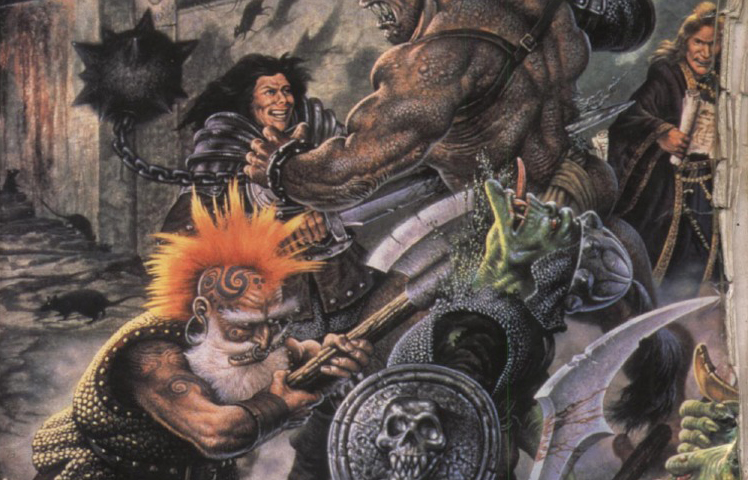

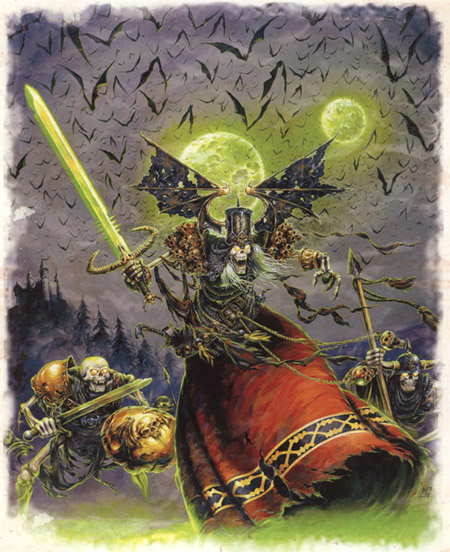

What made Warhammer Fantasy feel so unique in terms of setting was the grim and perilous nature of it all. Warhammer Fantasy was a much doomier, gloomier world. Here the tides of Chaos are constantly washing up against the shores of civilization. And even where Chaos’ ever-corrupting influence hasn’t spread, there are still murderous bandits, hard fighting, hard-drinking orcs, dragons, and more.

But what made WFRP shine was its scale. WFRP wanted to capture the feel of an individual in a world full of the massive battles that made up Warhammer Fantasy Battles. And the designers accomplished this not by sort of scaling down the deadliness of the world, but by assuming that characters would meet with an untimely end.

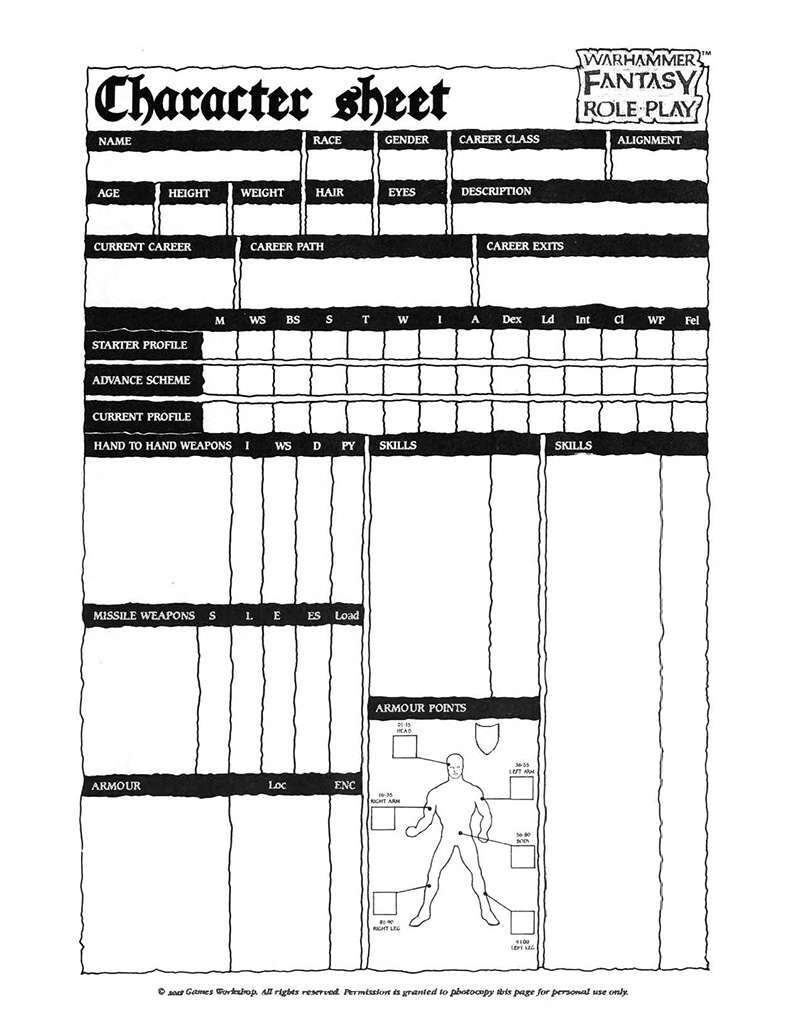

The rules of the game reflect this dichotomy as well. Early WFRP, when it was adapted was a much deadlier system. Unlike its counterpart, D&D, or any of the other fantasy RPGs that often had a swashbuckly or even super-heroic vibe, WFRP assumed that most characters could take one or two hits before becoming seriously injured, maimed, or killed outright. And WFRP was designed without regeneration or resurrection in mind–the only resource a player had were a limited number of Fate Points that would represent a character’s ultimate fate or destiny coming in to help beat those long odds.

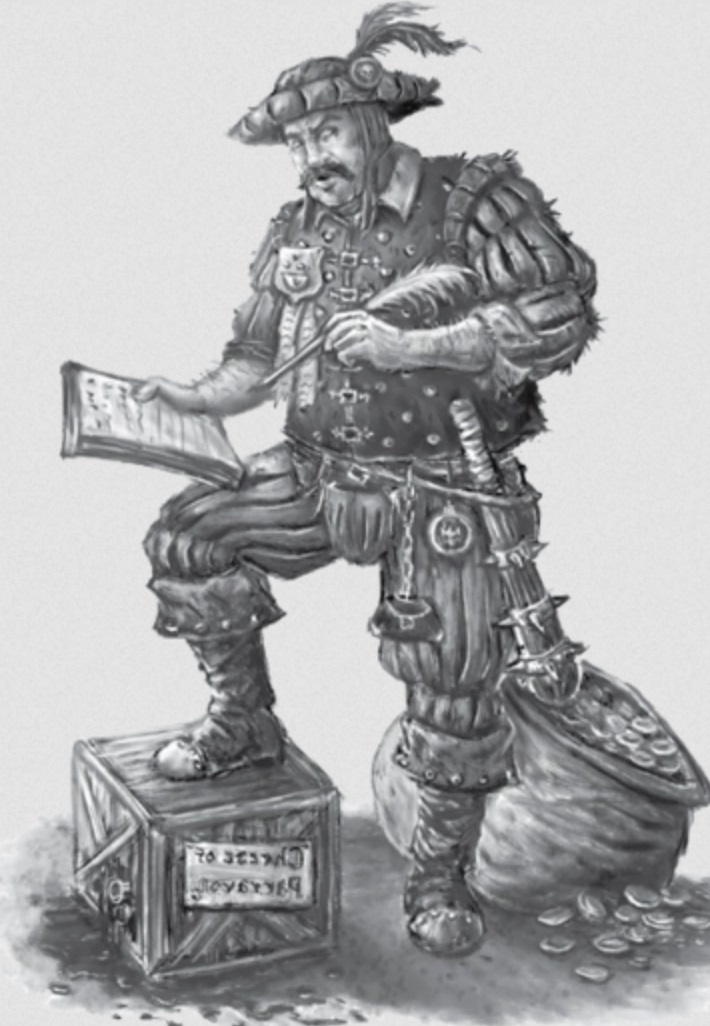

The rules also start you off– not as knights and great wizards– but as peasants. The game’s career system was designed to have characters progress through them. Instead of picking one class and sticking with it (for the most part), characters in WFRP would start off in a basic career like baker, rat catcher, night watchman, farmer, tax collector–an actual career that establishes the character before they take up adventuring.

Eventually, if you were lucky enough, you might get to pick an advanced career like thief or wizard’s apprentice, or mercenary, reflecting your character’s place within the world. And even if you do manage it, you still might be killed by almost any enemy. Even the lowliest adversaries could get a lucky hit that would bring you low.

At the end of the day, after all, you were still just a human. And you could still only take so many hits before meeting your doom.

Which has always been a part of the system’s great charm. It’s not just that you play a lowly character–but you play a lowly character with the possibility to rise to greatness or to fail spectacularly along the way. And when you mix that with GW’s dark humor and grimier sensibilities. The result is a unique, high-fantasy but low-class adventure that takes you from the grubbiest sewers to the darkest forests where danger and death lurk at the hands of any villain.

It’s why the system remains popular even to this day. Now, as Cubicle 7 revisits one of the best campaigns ever written, reimagined for a modern audience, a whole new generation has a chance to explore the grit and the grime of Warhammer Fantasy.