BoLS Prime: The Life And Times Of Gary Gygax

Gary Gygax is a name synonymous with early D&D. But where did the game designer who founded a genre get his start?

Dungeons & Dragons changed the gaming landscape forever, quickly rising from its humble beginnings in the wargaming scene of the late sixties and early seventies, to create an entire industry, atop which it still rules to this day. But that was not always the case. There was a time when the fate of D&D was linked inexorably to a company full of meteoric rises and equally as titanic crashes. But who linked their fates? Though D&D has two creators, Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax, it is the latter who helped launch D&D onto the scene, and to who D&D seemed intertwined. But how did Gygax create D&D? How did he part from it? And what became of one of the two founding fathers of RPGs?

Let’s find out. Let’s first go back to where it all begins–which in Gygax’ case is Chicago in 1938. There, he is born to Almina Emelie “Posey” and Ernst Gygax. Though he’s named Ernest after his father, most know him as Gary Gygax, thanks to his mother, who named him after Hollywood heartthrob Gary Cooper. There, he grew up four blocks from Wrigley Field:

I was born in Chicago about four blocks from Wrigly Field–the Bears played there back in those days… Because my maternal family has been in Lake Geneva since c. 1836, I don’t hate the Packers. Fact is, I’ll root for them if it doesn’t affect the Bears’ chances for winning. Back when Bart Starr was QBing the Pack, I often watched their games in preference to Chicago–what a traitor I am.

Even in those early days though, Gygax was given to imagination. In his younger days, he was part of a “pirate gang” known as the Kenmore Pirates. He and his friends would take up wooden swords and garbage can shields to have “wars” against the “enemy gang” that hung out at the north end of the long alley that both children played in. And even in these early days we can see the foundation of the action and adventure that D&D captures.

Gygax describes how his brother led to a makeshift jousting battlewagon…

My older brother was in high school, had some big friends, Jack Markam being the largest at around 6’4″ and near 300 pounds. when cleaning the basement as was his usual Saturday chore, my brother put Jack in my old baby carriage and wrecked it, so mother had him take it out to the trash. thus came into possession our War Wagon.

I had gleaned a rug pole from the alley, that being about 9′ long and around 2″ diameter…a marvelous lance! I was elected to ride in the sprung baby carriage, and armed with the lance, two of my pals serving as the team pushing the vehicle, and another couple of stalwarts flanking it to right and left, we forayed up to the dogleg in the alley where the “enemy kids” held sway. They spotted us forming up, got their shields, swords and rocks ready, and formed up to drive us away. The war wagon was too much for them, though. We were at least 50′ from them and charging when the lot of them broke and ran for it.

AdvertisementThat bloodless defeat ended their challenging our right to ranging the alley even though the war wagon was soon gone with the trash pickup and the mighty lance lost who knows where.

The defeated forces made the circular park across from St. Mary’s of the Lake their new domain, but they didn’t challenge us in armed combat again.

Of course, that’s one of the better scraps. Gygax recalls that another fight with an older gang of kids prompted his father to move to Lake Geneva, Wisconsin where his grandparents lived. It’s not exactly West Philadelphia to Bel Air, but it did bring Gygax to the eventual birthplace of D&D.

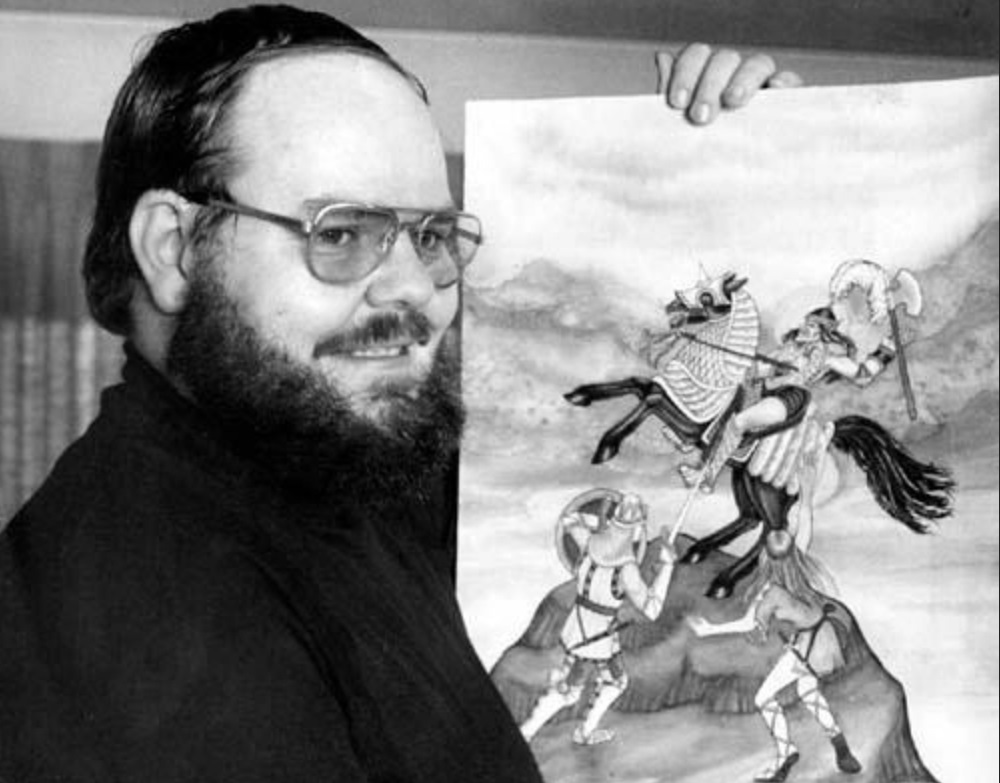

Gary Gygax grew up deeply immersed in pulp fiction, with Robert Howard, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Fritz Leiber, and Jack Vance all leaving their mark–a mark that can still be seen in the way that D&D operates. More than anything else, when the game was created, it was there to translate the narratives of a good pulp fiction story into a scenario you could play through as a wargame. And then later as a roleplaying game.

But D&D began as a wargame because Gygax was an avid wargamer. He came of age during the first big wargaming boom in America. In 1953, when Gygax was 15 years old, he and his best friend Don Kaye stumbled onto the wargaming scene, exactly at the moment that it was taking America by storm. This is thanks in large part to Charles Roberts and his game called Tactics:

In 1953, however, a revolution of sorts occurred in the commercial wargaming field. It was in that year that a young man from Baltimore published the first cardboard and paper wargame. Charles Roberts developed a game called Tactics. The game used a paper board with small cardboard pieces called “counters.” The counters were printed with military symbols indicating the type unit represented as well as with numbers quantifying such things as movement and combat strength. The game depicted two mythical post World War II powers and became immensely popular after its release by Stackpole Books Roberts’ creation boasted a number of advantages over the miniatures community. His board game was cheaper than an equivalent number of miniatures, and needed less time for setup as well as less room to play. Cardboard wargames could also be played solo and could easily simulate echelons of war (operational or strategic) above the tactical battlefield realm of the lead miniature. In fact, Roberts was so encouraged by the game’s success that he started his own company dedicated to publishing historical board wargames.

From that point on his Avalon Hill Company became the preeminent leader in such games, publishing over 200,000 units in 1962 alone. The company was also innovative and can be credited with establishing the hexagon (admittedly borrowed from Rand Corporation) as the standard mapboard device for regulating movement. Titles included such items as Gettysburg, D-Day and Stalingrad. The company went bust in 1964 for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was a growing mistrust of anything military due to the problems in Vietnam. Monarch Printing absorbed Avalon Hill, however, and the firm continued to publish wargames until very recently.

Tactics would redefine the wargaming scene, helping it to spread rapidly. Just a few years later, as conventions started to spring up, a burgeoning community found its roots. And at the heart of it? Wargaming magazines. Titles like Strategy and Tactics and Command Magazine would play a large role in helping to spread the wargaming scene. The more people began to play, the more ways there were to play.

Clubs would organize over mail, communicating through the “letters” section of gaming magazines. Events would come to a head at conventions, like the one in Lake Geneva, where Gygax and Arneson met, both playing experimental wargames. Here, at the very first Gen Con, Gygax had his first brush with medieval wargaming thanks to a game called Siege of Bodenberg.

Siege of Bodenberg, which would then go on to inspire the “Geneva Medieval Miniatures” game first published in the April 1970 issue of wargaming fanzine Panzerfaust. This game would later evolve into Chainmail, a medieval miniatures combat game that adopted two key rules of note: man-to-man combat rules, which are the combat rules that are still at the heart of D&D. These took wargaming from things that had 10 or 20 soldiers represented by a single model and reduced it to a 1-1 scale.

But far more influential would come the brush with the character-filled game known as a Braunstein:

Braunsteins–so named for the fictional town that the original iteration of the game took place in–were multiplayer miniatures wargames that featured two commanders of opposing armies, but would also assign additional, non-military roles. Players might take on the role of the town mayor, or banker, or university chancellor. And it’s here that we really see the truest form of an RPG, even in the days before D&D, as outlined in the Evolution of Fantasy Roleplaying Games:

“When nearly twenty people showed up [originator of the Braunstein, David Wesley] made up roles for them too. It was telling that the players received their orders in a separate room where Wesley briefed them, and were not allowed to share the information with each other. What was supposed to be an orderly set of instructions fell apart when two of the players, one an officer in the Prussian army, and the other a pro-French radical student, told Wesley they had challenged each other to a duel. Wesley was once again forced to improvise; he rolled some dice and declared that one had shot the other, with the winner imprisoned. The game continued well into the night, at which point Wesley realized that the players had taken over the game–his carefully crafted rules that would ultimately help determine who won no longer applied.”

Already it has the most important feature of a roleplaying game–arguing over rules. Arneson’s experiments with Braunsteins led to the creation of a medieval fantasy scenario incorporating ideas from the Lord of the Rings which would then shift in focus to dungeon exploration in Blackmoor. And in 1973, born out of Blackmoor and Chainmail, Arneson and Gygax created a game of cooperative exploration in a fantasy world that looked wildly different from the game we know today.

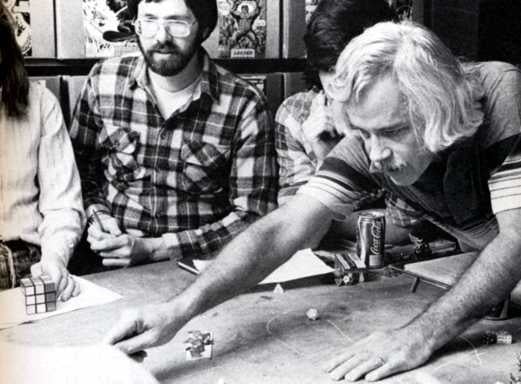

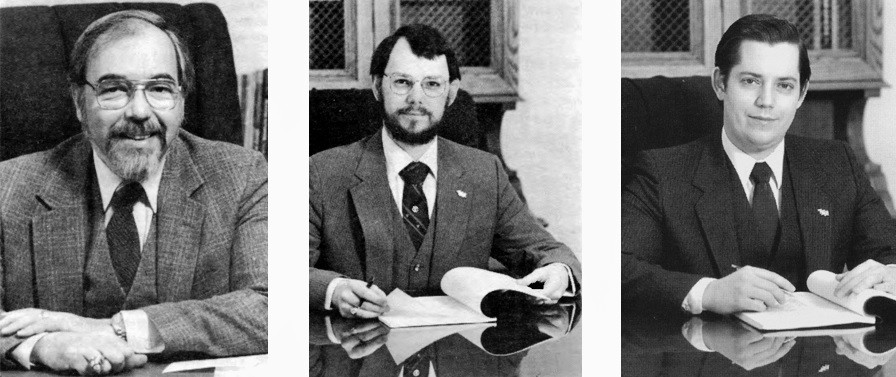

Just a year later, Gygax was ready to publish his game. Unable to find a publisher willing to invest, he teamed up with the friend whom he first started wargaming, Don Kaye, and the two formed TSR: Tactical Studies Rules. Unable to afford the publishing costs for D&D, the nascent company tried to push out another product, Cavaliers and Roundheads, in an effort to raise the money they needed to publish the first thousand copies of D&D. When that didn’t happen, Gygax turned to another gamer whom he had met at Gen Con, Brian Blume.

Now Gygax and Blume are names that call to mind a much more combative history. Famously Gygax would be ousted from his company by Brian and his brother Kevin, but not after extensive efforts by Gygax to try and regain creative control of the company. But it’s ironic that the real first salvo in the stormy air of TSR comes not from one of the Blumes, but from Gygax’ co-creator, Dave Arneson. It is lovingly dramatized in Empire of Imagination:

Gary quickly rose from his leather swivel office chair and lumbered down the long hallway to Brian Blume’s office. This path represented a steep departure from their last office layout, where their offices had been separated only by thin bedroom walls in the converted residential office space on Williams Street, known as the Gray House.

“We’re being sued,” said Gary.

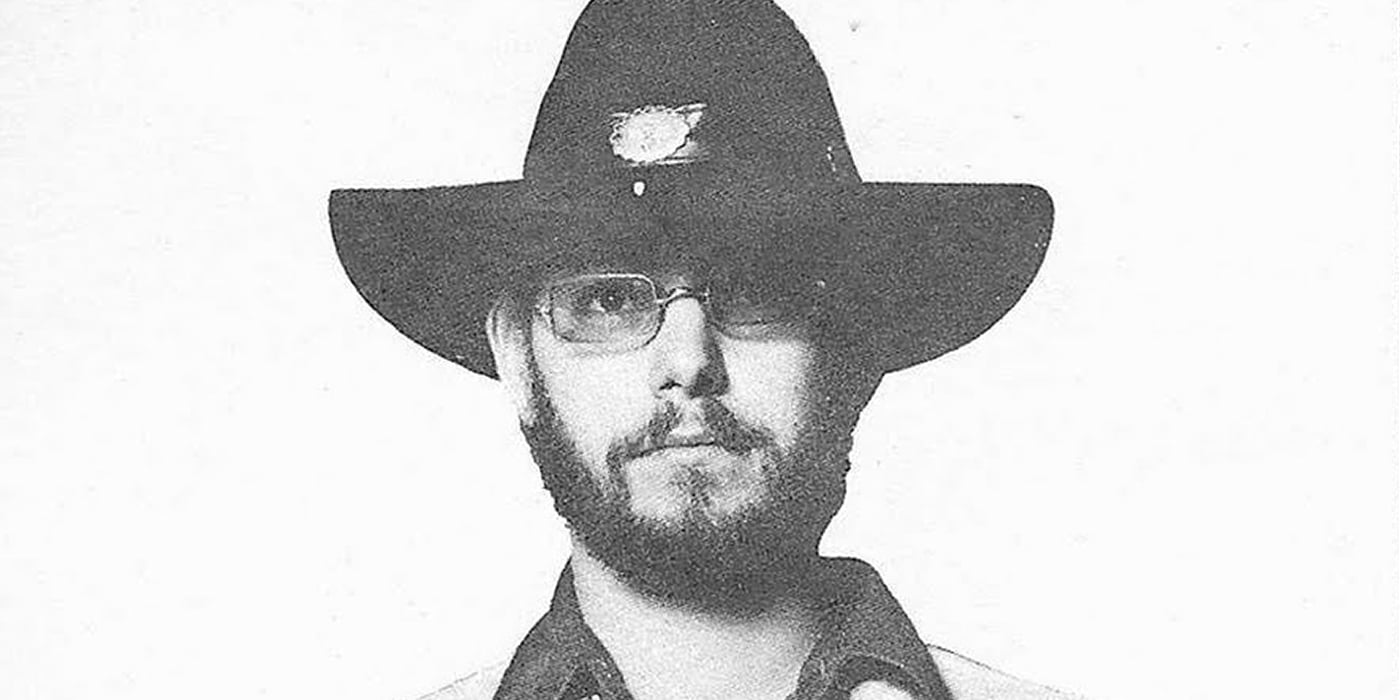

The bearded Blume looked up from a report he was reviewing. As usual, he was adorned in a Western-style shirt, boot-cut jeans with a large belt buckle, and of course cowboy boots. Although Blume was a Midwesterner, he had always fancied himself something of a cowboy.

Sued by whom?” replied Blume casually.

“Arneson!” Gary exclaimed as he threw a court document on Brian’s desk.

AdvertisementIt was February 1979, and Dungeons & Dragons had become a legitimate gaming phenomenon, roughly doubling its sales every year since its inception. Since 1977, however, TSR had invested much of its time and resources into a new system of Dungeons & Dragons, known as Advanced Dungeons & Dragons (AD&D), which now accounted for the majority of its sales. This new version of D&D bore little resemblance to the original system in its depth of gaming components and the quality of its books and supplements. The first of these AD&D materials was the hardcover Monster Manual, released in January 1978 to great success. This was followed in June 1978 by another high-quality rule book known as the Player’s Handbook. A third product was already in development and slated for release in 1979, the Dungeon Master’s Guide. The new books had been authored by Gary and edited by Mike Carr, who also contributed forewords to each. Arneson had neither worked on nor contributed to any of these prior to his departure, and because the new AD&D system had departed so greatly from the original D&D products, TSR had decided not to pay him royalties on these new rule books.

Now, it probably didn’t shake out the way that Michael Witwer has scribed it above. But a big part of Gygax’ adult life can be defined by the various troubles that followed him like this. The success of D&D caught the creator off guard–and that’s fair, it took the world by storm. But the newfound prosperity mixed with the creative frustration and political maneuvering at TSR led to an indulgent lifestyle that was a big part of the picture at TSR.

Because as Gygax grew in stature, so did TSR. When the company was doing well, it expanded rapidly, with no thought to sustainability. When it reached critical mass, the company, chasing a sense of “legitimacy” hired on business advisors who tried to curb some of the company’s practices, causing no end of friction between Gygax and the Blumes.

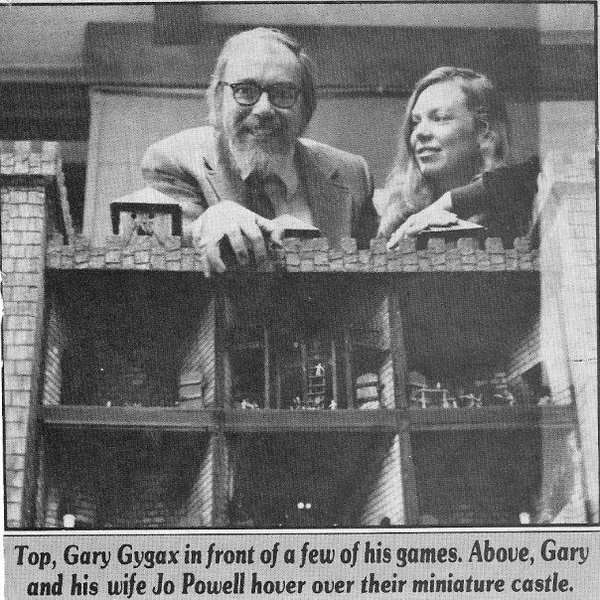

Frustration coupled with financial success is a recipe for rapid change. Gygax and wife Mary Jo, once active members of the local Jehovah’s Witness congregation, found themselves on the outs as the local group raised concern about the “satanic” game Gygax had created. Friction at work bled over into their real life, and Gygax is reported to have had a number of extramarital affairs which culminated in an “acrimonious divorce” in 1983.

Just in time for Gygax to go west, to Hollywood. And there, the lifestyle suited him… so long as the company was footing the bill.

As they mention in Of Dice and Men, Gygax famously ran up a $10,000/month expense.

Gygax did not live the life of an exile in Los Angeles. TSR was flush with cash, so he rented a mansion on Summitridge Drive in Beverly Hills and played the part of Hollywood hotshot, dining with movie stars, partying with beauty queens, getting driven around in fancy cars. Before long, his expenses approached $10,000 a month — more than $20,000 in 2012 dollars. According to some accounts, he paid half a million dollars to The Lion in Winter screenwriter James Goldman to write a script for a D&D movie.

But that’s tame in comparison to the details spilled in The Believer, which paints a more detailed picture of Gygax’ Hollywood antics.

Gygax rented King Vidor’s mansion, high up in Beverly Hills, with a bar, a pool table, and a hot tub with a view of everything from Hollywood to Catalina. He had a Cadillac and a driver; he had lunch with Orson Welles, though he mentions with Gygaxian modesty that “I find no greatness through association.”

Here a whiff of scandal enters the story. Gygax had separated from his first wife, the mother of five of his six children; he had not yet married his second wife, Gail. In the interim, well, it was Hollywood, and Gygax was in possession of a desirable hot tub. Gygax refers to the girlfriends who used to drive him around—he doesn’t drive; never has—and to a certain party attended by the contestants of the Miss Beverly Hills International Beauty Pageant. But he also mentions that he had a sand table set up in the barn, where he and the screenwriters for the D&D cartoon used to play Chainmail miniatures.

This is perhaps why Gygax, unlike other men who leave their wives and run off to L.A., is not odious: his love of winning is tempered by an even greater love of playing, and of getting others to play along. He ends the story about the beauty pageant girls with the observation that Luke, who was living with him at the time, was in heaven, seated between Miss Germany and Miss Finland.

Once he returns from Hollywood, with a successful animated series, Gygax would fit back into TSR for another year or two before being ousted by one of the rising business stars he introduced to TSR, Lorraine Williams. It’s the sort of corporate melodrama you’d expect to see on TV, but it played out in real life. Lorraine Williams, whose connections to considerable wealth, would allow her to purchase enough shares of TSR to assume control of the company and divest Gygax of his own interests in TSR.

But getting kicked out of TSR wouldn’t keep Gygax down. Before the ink dried on his severance agreement, Gygax was approached by some of his wargaming friends and given an opportunity to once again create another company. And so with the promise of a one or two million dollar investment from Forrest Baker, Gygax stepped back into the gaming business, founding New Infinities Productions.

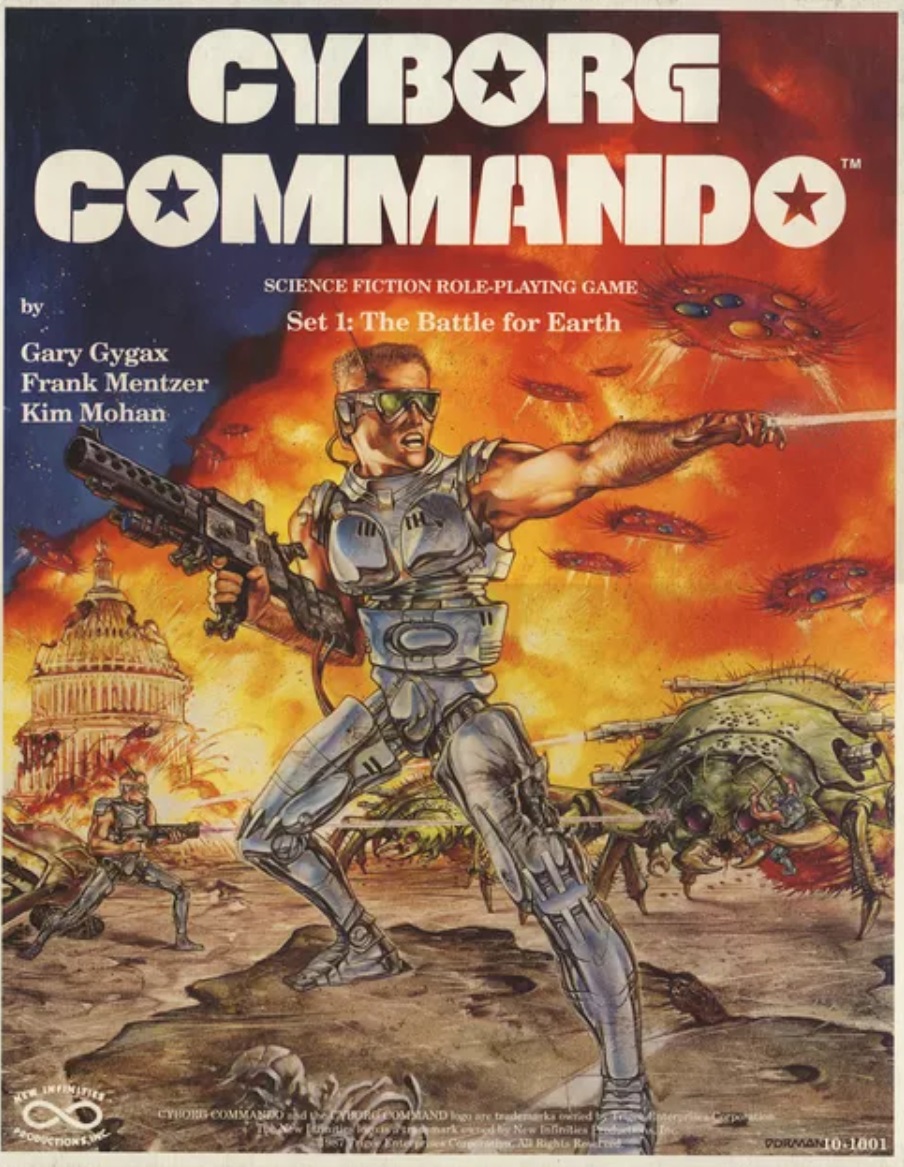

When Baker’s millions didn’t materialize, Gygax once again found himself in charge of a gaming company looking to make a product. Drawing upon the publication success of TSR and his Gord the Rogue character (to whom he retained the license), he licensed Greyhawk from TSR and began publishing new Gord novels, which kept New Infinities afloat long enough to develop a new Sci-Fi RPG, Cyborg Commando.

You probably haven’t heard of this game, and with good reason. Cyborg Commando was terrible, and the game flopped months after its publication run. Even so, the popularity of Gord the Rogue was enough to keep New Infinities going. At least until TSR rewrote the world of Greyhawk, taking it in a direction that Gygax was unhappy with. And so, Gygax at his most petulant, decided to destroy his version of Oerth as well as end the Gord the Rogue series, which deprived New Infinities of its only source of steady income. Not long after that, the company declared bankruptcy and dissolved.

If Gygax couldn’t have his cake, nobody could. That’s the larger-than-life personality behind D&D. Throughout his life he would chase the highs of Dungeons & Dragons, experimenting with form and function, with new engines and new media to disseminate the RPG. But it seems he could never fully escape D&D. Legal troubles constantly arose from similarities betwee Gygax’ work and that of D&D, an irony considering he was one of the more litigious voices at TSR in the early days.

But when a card-gaming company, Wizards of the Coast acquires D&D, it seemed like things would turn around. All the residual rights for D&D and AD&D were purchased–and for a handsome sum, and Gygax was once again writing columns about D&D for Dragon Magazine. There he would stay and bask in the glow of being one of gaming’s elders. He famously went on to voice himself in Futurama, and regaled the gaming community with tales of the old days. Until, in 2007, Gygax was diagnosed with a potentially deadly abdominal aortic aneurysm, which would ultimately cause his death in March 2008.

Gygax’ life was one of meteoric rises and falls. But his mark on gaming remains.