‘Doctor Who’ Changes Davros to Address “Disabled Villain” Trope — and It’s Complicated

Since the 1974 Doctor Who episode “Genesis of the Daleks” the titular villain’s creator has always looked the same. Until now.

There’s a long tradition with modern Doctor Who where, between seasons, fans get mini-episodes to tide them over. Oftentimes these episodes appear during Children in Need, a telethon that raises money, awareness, and aid for disadvantaged children. David Tennant‘s first full outing as the Doctor occurs during Children in Need.

And in fact, David Tennant returns to that grand tradition with this year’s Children in Need. This time Tennant’s Doctor accidentally lands himself at a moment early on in the creation of his greatest nemeses the Daleks. And in comedic fashion the Doctor accidentally impacts the Daleks in multiple ways: he gives them their name, their catchphrase “Exterminate!” and their infamous secondary weapon—the plunger.

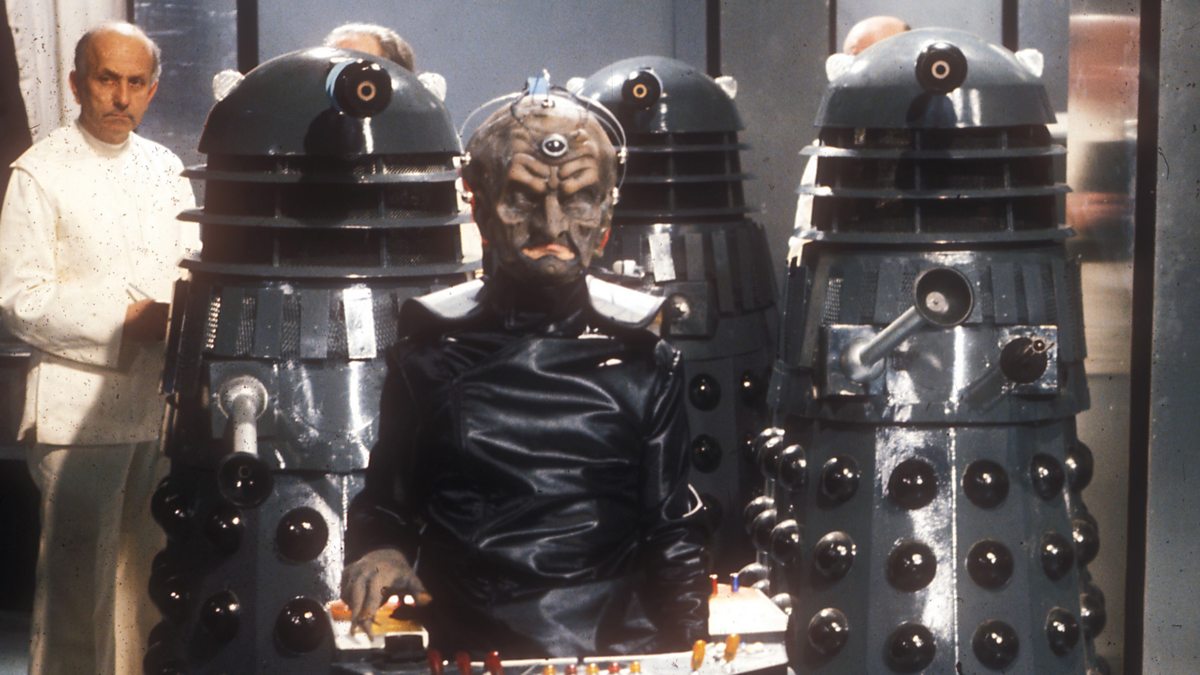

But before all that we see a new take on a very old character: Davros. Davros is the creator of the Daleks. And since his first appearance in “Genesis of the Daleks” he has a very distinct look. Davros is in a wheelchair (shaped like the bottom half of a Dalek) while his face and body are heavily scarred. This look continues for Davros all the way through into the modern series with the last appearance of the character with this design in the 2015 episode “The Witch’s Familiar”.

However, in this latest Children in Need special, Davros looks completely different. No scars. No Dalek wheelchair. And these changes are, as of now, permanent. Russell T. Davies has a very specific reason for this change and it’s very much worth examining.

Why Davros Has a New Design

During the war between the Thals and the Kaleds on Skaro, Davros suffers serious wounds after a Thal bombardment. As a result of his injuries, Davros spends the rest of his life in a wheelchair.

Except that’s no longer the case. In the 2024 Doctor Who Children in Need Special Davros appears standing and with no injury. Fans with a knowledge of Davros’s history may assume this mini-episode takes place prior to the Thal attack. However, according to showrunner Russell T Davies, this is a permanent change.

In the corresponding behind-the-scenes Doctor Who Unleashed special Davies explains the reason for Davros’ transformation.

“Time and society and culture and taste have moved on, and there’s a problem with the old Davros: he’s a wheelchair user who is evil,” Davies explains. “I had problems with that. A lot of us on the production team did too, associating disability with evil. Trust me, there’s a very long tradition of this.”

While Davies is quick to say he is “not blaming people in the past” he insists “the world changes”. “So we made the choice to bring back Davros without the facial scarring and without the wheelchair—or his support unit, which functions as a wheelchair,” says Davies.

And Davies is clear that the new Davros is here to stay. “Things used to be black and white; they’re not anymore,” he says. “Davros used to look like that, and now he looks like this. We are absolutely standing by that.”

Unquestionably, Davies has noble intentions here. Let’s talk about where this stereotype comes from and what else Davies is doing with the modern series to combat it. But let’s also look at this new Davros and honestly ask: does this change match the mission statement?

The Disabled Villain Trope

Even the earliest forms of media use disability and deformity as a shorthand for villainy. Want someone to know your guy is a proverbial black hat? Give him a scar. Want to explain why your villain commits her evil acts? Say it’s because she’s deformed and jealous of pretty people. Russell T Davies is right: this happens in visual narrative A LOT.

And the reason dates back practically forever. Some faiths have taught the idea that physical disability represents past sins or some kind of inherent moral failing. It’s easy to ‘other’ someone—to see them as different or even less if they look different from you. That’s the very foundation of bigotry.

The way that translates in media for disabled performers is that the kinds of roles on offer can be limited to playing villains or people who are helpless. Davies wants to course-correct by moving away from these tropes. More than that, he wants to ensure more diverse opportunities for disabled performers as well as other performers who face challenges in what, who, and how they are offered work.

We can already see Davies taking decisive action on this. Actors of color, queer performers, and people with multiple disabilities (including at least one so far in a wheelchair) all feature in upcoming Doctor Who episodes. The characters these actors play are not defined by any one element of their identity. And that’s great.

That brings us back to Davros. How does taking the disabilities and injuries away from this character impact him, the actors who play him, and his overall impact on our real world?

Old Vs. New

Original Flavor Davros is a man in a wheelchair with missing limbs and visible damage to his entire body. He’s a supervillain without the use of his legs who guides his own people’s mutation towards a shape where every single one of them also has no functioning legs. And as a result, the Daleks, have one goal: to wipe out every other lifeform in the universe.

It’s pretty easy to see how Davros plays into the Disabled Villain Trope. Part of what makes him Davros is being a genocidal leader who only wants other deformed people without the use of their legs to exist. Davros is a near-perfect archetype of the trope. What’s more, he’s not historically been played by disabled actors. However, if a disabled actor were to play Davros, the problem of lack of opportunity would still exist for disabled performers, especially outside of Doctor Who.

There are also arguments for why changing Davros is not a perfect solution. There’s another trope out there that involves taking a character who uses a wheelchair and making them no longer need it. Bobby Singer in Supernatural, Felicity Smoak on Arrow, and Barbara Gordon across the Batman mythos all have points where they use wheelchairs and then do not.

Watching that happen in real-time can be frustrating, especially if you are disabled. When a character becomes disabled, the opportunity to tell stories from their perspective arises, and then it’s gone just as quickly. People want their stories told in the long term. The possibility to do that with Davros is there, it just has not been done yet.

There’s one other aspect to Davros, and villains in general worth discussing.

Playing Davros (and Villains in General) is Fun

Being a megalomaniacal, cackling monster isn’t something one gets to do in the day-to-day. And since there’s no actual consequence, taking on a campy villain persona is FUN. Davros, with all his over-the-top theatrics, can be a dream role. And I suspect there are loads of disabled performers who would leap at the chance to portray him.

This is somewhat reminiscent of the recent debate over the character of Captain Angel on Star Trek: Strange New Worlds. Trans actor Jesse James Keitel plays a nonbinary femme pirate in love with Spock’s half-brother Sybok. And Keitel devours the scenery as Angel. And she’s having fun!

But Angel is unquestionably a villain. And there are those who don’t wish to see trans people portrayed as deceptive enemies when there are so many tropes already pushing that narrative. However, Keitel loves the part. She plays an active role in the costume design which informs much of Angel’s personality. And there are nonbinary, trans, and other queer performers all over modern Star Trek right now. Why shouldn’t Keitel get to live, laugh, love it up as Captain Angel?

Ultimately, Russell T Davies makes the decisions with Doctor Who. His decision is that Davros has no disability. Largely, I think that’s a fair call given the history. I just hope that sometime soon another deliciously villainous Doctor Who character comes along for a disabled actor to play. And that roles of all types for people with disabilities continue to be more readily available.